Bron Kobe Shaq Magik

Some thoughts on watching basketball, making art, and (obviously) the Red Hot Chili Peppers

Hi. Welcome to Sports Stories, an illustrated newsletter at the intersection of sports and history.

If you’re not already a subscriber, please consider joining up here — we have both free and paid options. If you enjoy Sports Stories, please share it with your friends. Word of mouth is our best (and only) means of publicity.

You can also buy some merch — including a t-shirt featuring art from this very issue of Sports Stories — at our awesome web store.

I.

Here is a fact about Adam and I: a big part of our friendship doesn’t have anything to do with sports or stories, writing or art. In addition to liking each other, and having similar values, and both being dads, and all that stuff, we are also two LA dudes with an abiding interest in the general beauty and weirdness of the city in which neither of us lives anymore.

One part of that abiding interest is that we both like the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Not just as a band but as a longstanding LA phenomenon; an institution whose vibes capture something essential about Los Angeles. Adam and I have talked about this many times. For example, we recently learned that we were both at the same Red Hot Chili Peppers/Stone Temple Pilots concert at Irvine Meadows in September of 2000.

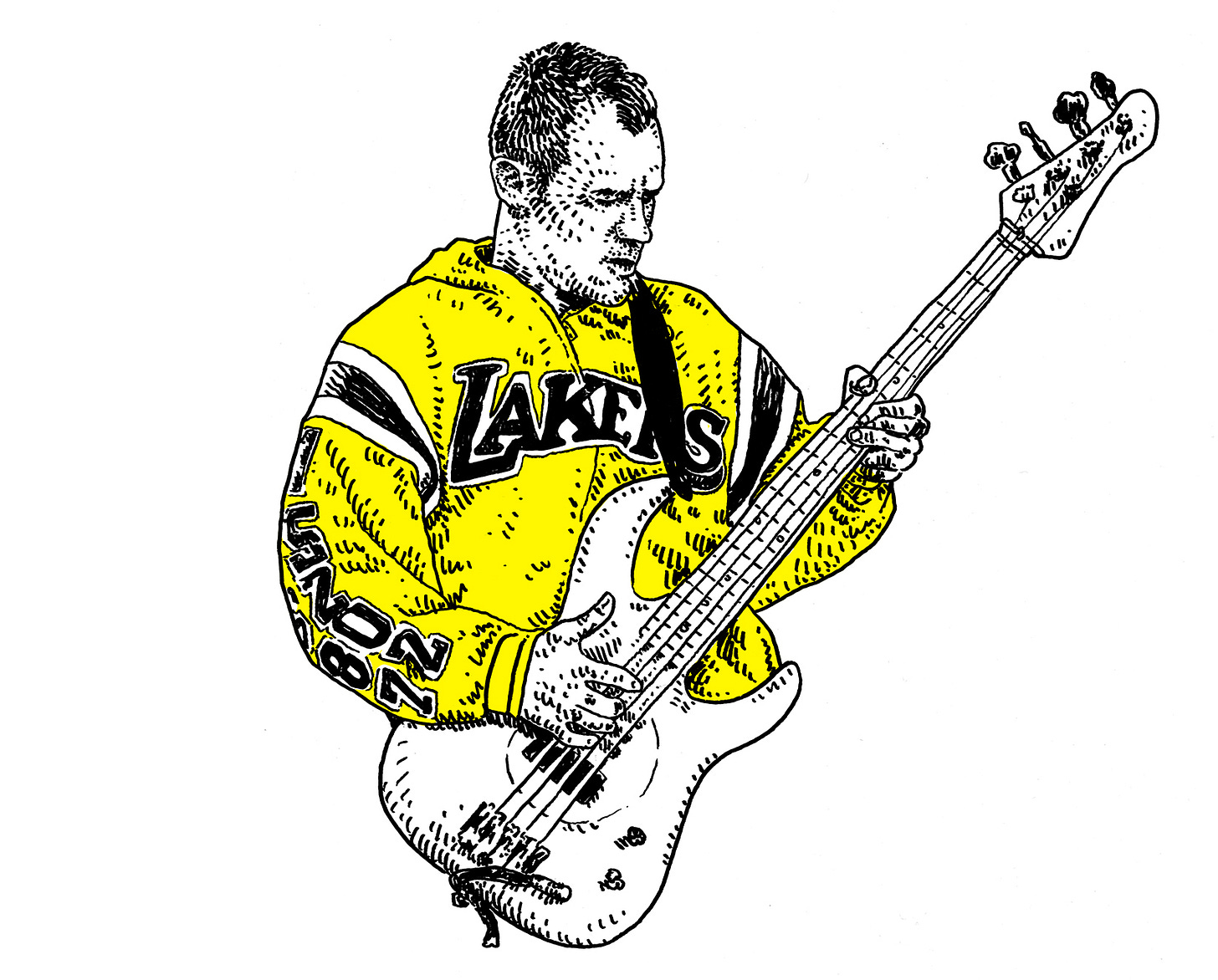

So it was not that surprising when after we published our previous issue on cowgirl Tad Lucas, Adam texted me, “Let’s do Kiedis and Flea next week.” Actually, it felt kind of normal. Anthony Kiedis (vocals) and Flea (bass) are not professional athletes, technically. But they do love basketball and the Lakers in a very public way. And Flea is actually a pretty decent hooper for a 5’5” rock musician. He was a regular in MTV Rock N’ Jock basketball games in the 1990s, and one year he won the 3-point contest by draining 6 consecutive jumpers:

II.

Early in the pandemic, I started getting into jogging. It’s not something I ever really thought I would say about myself—that I run for pleasure or a feeling resembling pleasure. But now it is a part of my life, and a good one. Most of the time, I like to run in silence, and just clear my head. It turns out that there’s secret magic in the movement and the rhythm of running that can get you into a good mental space where you are simultaneously thinking clearly about everything in the world and not thinking about anything at all.

But sometimes that kind of transcendence is too heavy for me. So I also listen to books on tape through a public library app called Libby. This was how I came to hear Flea’s memoir, Acid For the Children.

Acid for the Children is a legitimately wonderful book about being a kid, growing up, and making art. Honestly I couldn’t believe how well-written and open-hearted it was. Plus, Flea’s childhood was absolutely bonkers. It’s full of crazy stories and offbeat characters and ideas that didn’t even seem good at the time. But in many ways, the book is really about the supernatural feeling you get when you are totally immersed in a process that you care deeply about—the search for that feeling, and the challenge of trying to capture and sustain it once you first find it.

Flea found it in music, obviously. First playing trumpet, then bass. But he also found it in sports. He writes a lot in the book about playing basketball for hours upon hours at the playground. He writes about basketball as if it is almost sacred.

“My sanctuaries of friendship, books, basketball, music, and nature kept me sane. Even though I didn’t have a clue of how to stop running myself ragged, to be still, and know myself, or treat my body itself as one of those sanctuaries.”

The idea that there is some overlap between what professional athletes do and what artists do is not new or original: the focus on craft, the obsessive perfectionism, the interplay of individual ambition and collective chemistry. I think about this all the time. Is the work we do a means to an end? (A finished product that will hopefully move or inspire or entertain people)? Or is doing the work an end in itself? The stuff Adam and I write and draw is all going to be forgotten eventually. But we’re still compelled to keep writing and drawing because somehow writing and drawing are essential to who we are and how we want to live.

There’s a version of this kind of thinking that is very competitive and puts an emphasis on capital G-Greatness and capital P-Perfectionism. You might call this the Mamba Mentality. But what I dig about Flea’s book is that he seems to seek something more personal than a generic form of excellence; he is less concerned with external validation than what doing the work does for his own spirit.

What is the point of playing a sport (or watching it) if it doesn’t make you happier? Or more fulfilled?

III.

Acid for the Children is also very much a love letter to the artists who inspired its author. I appreciated how unabashed Flea was in his fandom. He had heroes, and those heroes meant a ton to him. They weren’t personal relationships, but his relationships with Jimi Hendrix and Dizzy Gillespie and the late 1970s Lakers were still deeply personal. As a kid, he used to wear a fake gold chain to look like Lakers guard Norm Nixon. As an adult, he sits courtside at Laker games and wears ridiculous purple and gold outfits and embraces all the obnoxious and gratifying traits of a superfan—be that talking shit online, or referring to a team as “we” or whatever it is. His bandmate Anthony Kiedis got kicked out of a game a few years ago for arguing with Chris Paul.

“Basketball is so beautiful, and, like all fine arts, a metaphor for all that uplifts or ails humanity,” Flea wrote on Instagram after the Lakers won their title in the bubble. You know he meant it. Then he went on to tell a story about playing a show in London with Ornette Coleman and Patti Smith, going back to his hotel room, and watching a previous Lakers’ championship alone, with tears in his eyes.

The job of writing about sports and then promoting that writing on the cruel, cruel internet can wash some of that fandom away. You get cynical and then you get defensive and then you don’t want to leave yourself vulnerable to heartbreak or humiliation. But of course that’s the deal with anything in life. The more you put your heart into an act, the more vulnerable you make yourself, whether it’s being a fan or being an artist or being in a relationship or being a parent, the greater the reward. The ability to fully immerse yourself in something you care about without concern for what other people might think or how you might get hurt—that’s a gift.

You can learn this lesson from Flea or you can learn it from Norm Nixon. Ultimately, you just have to try and learn it.

IV.

I can’t believe I’m writing about the Red Hot Chili Peppers, a ridiculous band that has somehow been around for longer than I have been alive. They were never even my favorite—I was more into Sublime, if we’re getting into the time and place. But they were so definitively themselves and they were so ambient in the Southern California air. Like the Lakers, the Chili Peppers were this fully formed institution. They had a look and a feel and even a mythological history.

And now here I am trying to say something quasi-meaningful about art and life and sports, and watching concert clips on YouTube. It’s funny how these little moments from your childhood gain meaning years and years later.

I remember the first time I truly listened to them beyond all the songs on the radio. At some point, in the early or mid-nineties, my cousin William brought the Blood Sugar Sex Magik CD over and we sat in my room and played the whole thing. It was music that didn’t come from grownups. I remember that concert at Irvine Meadows—my first ever real rock concert. I had just turned 14. A couple months earlier, Shaq and Kobe won their first title together. Every third car on the freeway had a Lakers flag fluttering out the window. It felt like the start of something.

Thank you for reading Sports Stories. We’ll be back to our regularly scheduled programming next week.

I so relate to this: “The stuff Adam and I write and draw is all going to be forgotten eventually. But we’re still compelled to keep writing and drawing because somehow writing and drawing are essential to who we are and how we want to live.”