Welcome to Sports Stories, an illustrated newsletter at the intersection of sports and history. If you’re not already a subscriber, please consider joining up here.

If you’re a longtime reader, or just enjoy this post, please consider doing us the favor of sharing Sports Stories. You are the reason we do this, and also happen to be our best (and only) marketing system.

One of the first important lessons I learned in sports writing was this: every pro athlete is a miracle. Every person who fulfills their potential and gets the opportunity to play a sport for money in front of adoring crowds (large or small) deserves appreciation. The job is so hard, and so rare, and so tenuous, that the lasting presence of, say, John Salley, at the end of an NBA bench deserves to be celebrated. Because there are always reasons it shouldn’t happen. There are always circumstances.

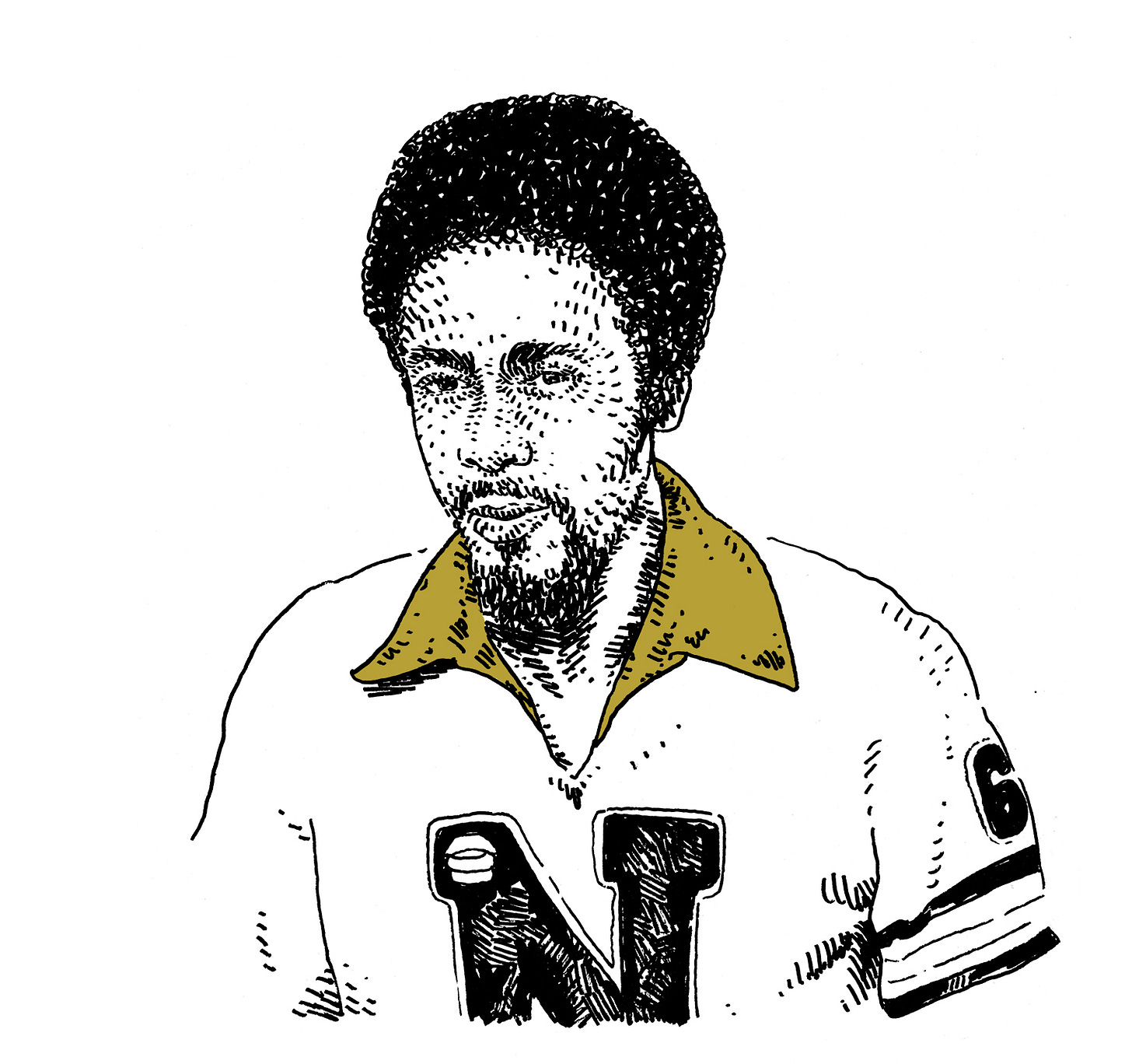

Every town has a Curtis Jones. Sometimes it’s a bad injury, or a tragic accident, or a missed opportunity. Someone picked the wrong day to have a bad day, or catch a cold, or miss their bus. But only one town had the real Curtis Jones. Detroit. And for Jones, it was so much more than a missed opportunity. The circumstances -- well, everything was circumstances.

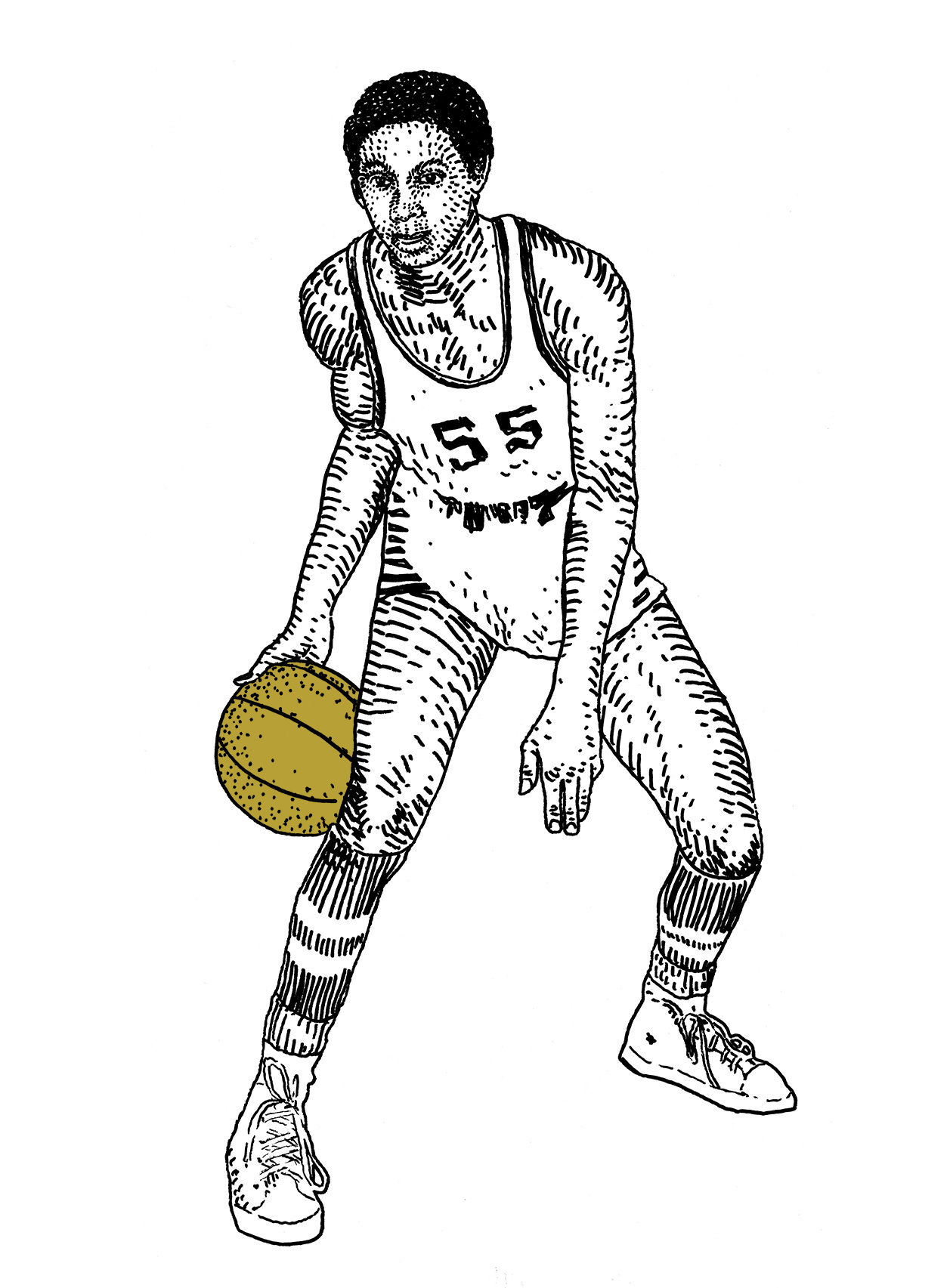

Jones grew up in Detroit when the city was cresting: the cars were rolling off the lines, and the hits were rolling out of Motown Records. His father worked on the assembly line for Chrysler. As a boy, Jones used to dribble a basketball everywhere he went. From the family home all the way downtown and back. Four miles there with his left hand, four miles back with his right. Basketball was all he loved.

When he was 12 years old, Jones’ father died of cancer. “I took it hard,” he said later. “And I didn’t care about much at all for a long time.” He narrowed his world to the basketball court. He was smallish. Short of six feet, and skinny. But it didn’t matter. The word everybody seemed to use was genius. He could make the ball do whatever he wanted. He could see the court with his eyes closed.

Jones played at Detroit Northwestern High School, where one of his teammates was the future MLB slugger John Mayberry. In 1967, he hit a buzzer beater to defeat a rival team that featured future NBA players Ralph Simpson and Spencer Haywood.

“He was just a phenomenal player,” Haywood said later. “For young players that want to know what it was like. The stuff that Magic Johnson did as a player, Curtis Jones was the first player to do it. Not that kind of size, but he had the skillset to do all of those things. He was just incredible.”

In the intervening years, the legend of Curtis Jones has grown increasingly vague and mystical. His legacy exists in the memories of people like Haywood. The tales of his skill get passed down from generation to generation in Detroit. He could dribble across the court in three strides and dunk it. He could go an entire game without taking a single shot, racking up assists, only to casually sink the winner as time expired. There is no known surviving video footage of Jones on the basketball court. This is because of what happened to him in high school and shortly afterward.

Jones was the victim of a system that was designed to squeeze the greatness out of him and offer nothing in return. He had learning disabilities from a young age, but never got the support he needed in school. He never learned to read or to write his own name. But he was shuffled along from grade to grade, all the way through high school, because of what he could do on the basketball court.

He didn’t have the grades or test scores to attend the University of Michigan, where his high school coach had taken a job as an assistant. So after graduating from Detroit Northwestern, he took a deal. Go off to junior college in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, and get your grades up. When you do, there will be a spot waiting for you in Ann Arbor.

But that never happened. In Idaho, Jones was isolated. He was at a college full of white people in a city full of white people in a state full of white people. And he still couldn’t read. How was he supposed to get his grades up with no friends, no family, no institutional support? He broke down emotionally. Coeur d’Alene was nothing like Detroit, except for one thing. The institutions in his life only needed him to be one thing: a basketball player.

As I was learning the story of Curtis Jones I was struck repeatedly by the amount of people who used the word “genius” to describe him. There’s something poignant about it. He was a basketball genius, and a thoughtful person off the court. But he couldn’t read or write. I began to think about how absurd it is that we tie athletic success to academic success. I began to think about how reading and writing is such a narrow way to judge a person’s intelligence, and ultimately measure their value.

I began to think about the fact that decades later, we still live in a country that values athletic genius, and has an entrenched sports system that pretends to care about the well-being and academic success of its most talented athletes while it is in fact only extracting value from them. Curtis Jones didn’t need Detroit Northwestern, or Northern Idaho Junior College, or the promise of the University of Michigan to get to the NBA; he didn’t need the NCAA’s hypocritical definition of a student-athlete. He needed somebody to care enough to help him.

Curtis Jones became an urban legend. descended into mental illness. He moved back to Detroit. He existed in the present, wandering the streets of his old neighborhood, and in the past, frozen in glory. He dwelled on that game winning shot from 1967. He found himself in and out of the Northville psychiatric hospital.

It didn’t have to go that way. Spencer Haywood also suffered from learning disabilities. He had also been unable to read or write. But in high school, he finally found the support he needed. And when he went off to a junior college in a lonely place, he made it out, to the pros, the Hall of Fame, and a successful post-playing career in business.

In 1982, Jones and his family launched a lawsuit against all the institutions that had betrayed him. The Detroit Public Schools. Northern Idaho Junior College. The former coach who had dangled the promise of the University of Michigan before him. He had a compelling case to make. But after years of legal battles, the Michigan State Supreme Court declined to hear it.

“I don’t know who’s to blame except maybe all of us,” Haywood said later. “Curtis’s failure is America’s failure.”

In 1990, a writer named Shelby Strother caught up with Jones and his family for a long and heart-wrenching story in the Detroit Free Press. There’s Curtis Jones in the small room at his mother’s home. There’s Curtis Jones reenacting that fateful shot from 1967 in the alley behind the house. There’s Curtis Jones plainly laying out the painful circumstances that derailed his life, and then pleading, pleading for someone to understand that it didn’t have to be this way.

“I got too close to my dream and my soul could not bear it. But someone let me get too close, you hear me? I can’t read, can’t write. Never could. I knew it would catch up to me. I always had an inferior complex. Man when you can’t read nothing, you can’t feel no other way. But I can still play ball like a bitch. Still the greatest dribbler of all time. You hear me?”

Jones passed away in 1999.

Related Reading

Unsurprisingly, Curtis Jones was featured prominently in Detroit newspapers both during and after his playing career. But the best story I read on him was the aforementioned 1990 feature by Shelby Strother. The article is not freely available online, but please feel free to email if you want a PDF. Honestly, this story was so good that I went and looked up the author because it was amazing to me that he never became famous -- or as famous as sports writers get.

It turns out, the feature on Jones was one of the last big stories Shelby Strother ever got to write. He died of cancer in 1991. He was only 44 years old. Before that, Strother had written for papers in Florida and Colorado. I enjoyed this remembrance of Strother by one of his mentees, a journalist named Reggie Connell.

There was also a 30-minute documentary about Curtis Jones released in 2015, called Fouled Out. It features a lot of Detroit hoops legends (including Haywood and Jalen Rose) talking about Jones and his legacy. You can stream it for free on Vimeo.

Thanks for reading Sports Stories. We’ll see you next week.

"One of the first important lessons I learned in sports writing was this: every pro athlete is a miracle. Every person who fulfills their potential and gets the opportunity to play a sport for money in front of adoring crowds (large or small) deserves appreciation."

Beautifully said.