Welcome to the first issue of Sports Stories, a newsletter written by Eric Nusbaum, and illustrated by Adam Villacin. Every week, we’ll be learning about sports, history, and sports history. We hope you enjoy Sports Stories — and that if you do, you share it with your friends, families, and table tennis practice partners.

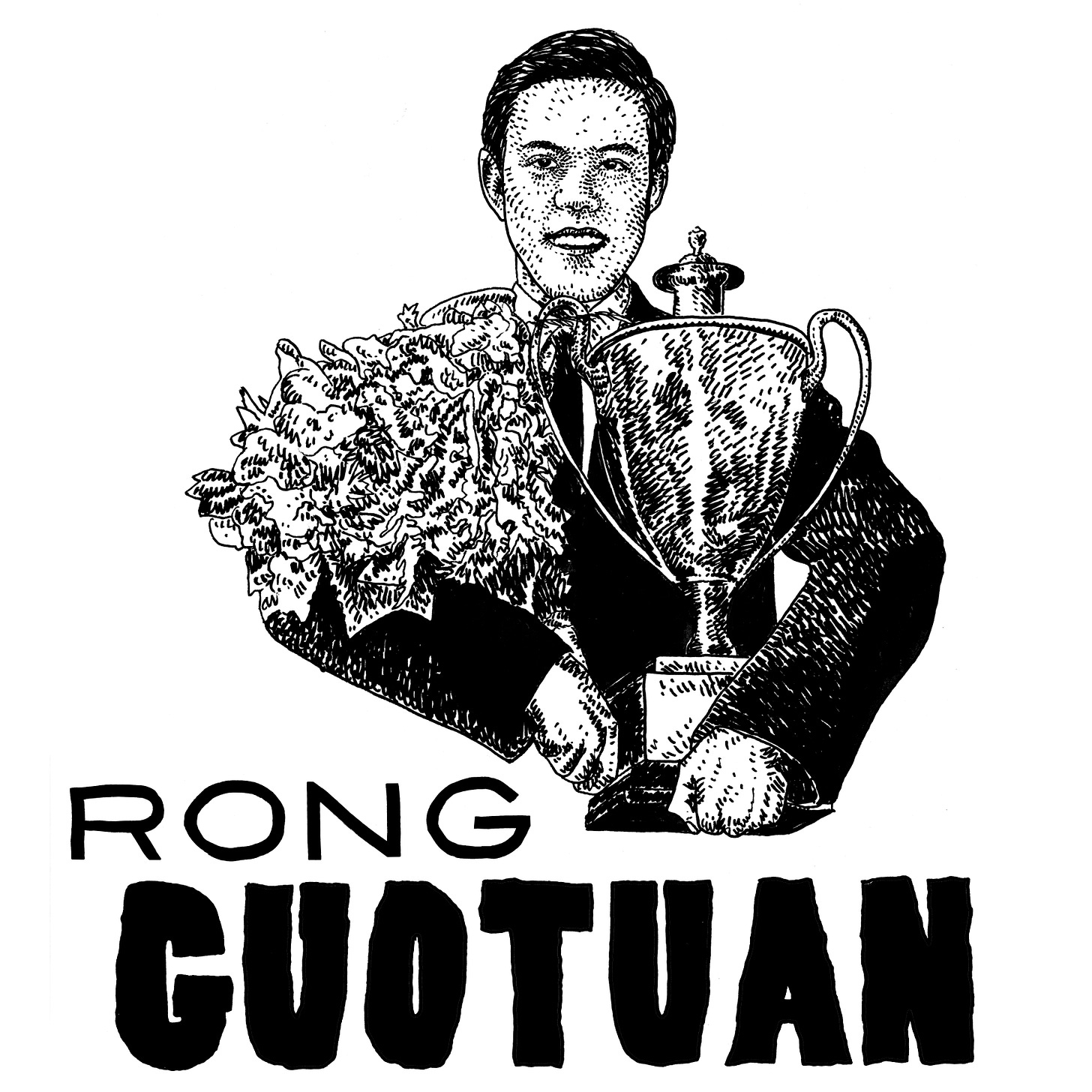

In 1959, a 21-year-old named Rong Guotuan entered the field at the World Table Tennis Championship in Dortmund, Germany with low expectations. Rong was a tall, skinny kid, with a parted haircut. His day job before becoming a full-time ping-pong player was as the librarian at a union hall in Hong Kong. The outlines of his life are well-recorded, but the details are hard to chase down – especially for a person (like me) who speaks neither Mandarin nor Cantonese. I know that like his teammates on the Chinese national team, he played with a penhold grip (for more on table tennis grips, scroll to the bottom of this newsletter). I know he had a crisp, accurate forehand and an acrobatic backhand block that flickered like a light. I believe that before Dortmund, Rong had never even played in an international tournament.

The tournament in Dortmund was held in a massive warehouse-like hall, full of tables. The sounds of footsteps on the wooden floor, and ping-pong balls on the wooden tables filled the air. When Rong leaped around the table, his bangs flipped up and down off his forehead. As the field narrowed, tables were slowly removed from the hall until finally, in the championship match, there was only one table left at the center of the cavernous space. On one side of that table stood Rong Guotuan. This would not be the last time Rong Guotuan seemed to be at the center of everything.

The very presence of Rong Guotuan in Dortmund was something of a miracle. For one, he had been born and raised in Hong Kong – not in mainland China. Before Rong was born, his parents had fled across the water from the coastal Chinese city of Zuhai, searching for stability and opportunity. Over the course of Rong’s life, his family’s fortunes had sunk steadily. The onset of World War II had cost his father a good job at a bank. He became a cook in the galley of a fishing boat.

Rong was a quiet, introspective person with a gangly physique. He did not give off the appearance of a serious competitor or a great athlete. But he was both. As a teenager, he contracted tuberculosis only to come back stronger than ever. He spent hours in the union hall in Hong Kong, practicing his serve across an empty ping-pong table. The sport has evolved in the decades since Rong played, but he was ahead of his time; many of those evolutions owe themselves to Rong’s own inventiveness, especially with the serve. He had a way of hiding his spin on a backhand serve that drove opponents crazy.

Just before he turned twenty years old, Rong became Hong Kong’s men’s singles champion. Soon after that, he defeated the Japanese champion Ichiro Ogimura in an exhibition match. This, he hoped, would be the springboard to a great international career. But when the roster was announced for Hong Kong’s national team for the upcoming Asian Championship in 1957, Rong’s name was left off the list. The reason for this is not exactly clear. But it would not be unreasonable to consider that his parents’ mainland roots were a part of it. The Communist Revolution had ended less than a decade earlier; Hong Kong, under British colonial rule, remained an anti-Communist outpost.

Throughout the 1950s, hundreds of thousands of mainland Chinese left for Hong Kong each year. But Rong did the opposite. Chinese officials scouted him and wooed him. Two other Hong Kong table tennis players had made the journey back to the mainland in the years prior: Fu Qifang, and Jiang Yongning. Now, Rong would too.

Just before he left Hong Kong, Rong met up with one of his close friends and playing partners. Steven Cheung. As Rong left to try his fortunes in China, Cheung was on his way to make a life in Canada. Rong taught Cheung a serve he had developed, and gave him some words of encouragement. According to a story Cheung wrote years later, the serve and the encouragement would stay with Cheung forever. (Cheung would go on to become a well-known economist studying under Milton Friedman at the University of Chicago. In his retirement, he would be charged with tax fraud in Seattle, and like Rong had before him, Cheung would wind up in China.)

The China that Rong’s parents had fled two decades earlier was a very different place from the China Rong came to in 1957. Now it was the People’s Republic, and Rong saw only the best of this new nation. He was feted by Chairman Mao’s trusted lieutenants. According to Nicholas Griffin’s book Ping-Pong Diplomacy, Rong was even put up in a home that had once been occupied by Chiang Kai-shek. When he had a tuberculosis relapse, he was sent to recover for six months in a sanitarium.

When Rong Guotuan walked into the Guangzhou Institute of Physical Education for the first time in November of 1957, he declared that within three years he would become a world champion. There was little reason for anybody to believe him. China was not yet the global table tennis power it is today. And Rong, while obviously talented, had yet to demonstrate that he could execute consistently at a high level. He was just a kid, practically. World champion in three years? Actually, it would not even take him two.

The 1959 tournament in Dortmund was Rong’s first attempt at fulfilling his declaration. Rong ran through one opponent after another, until finally he found himself in the final against the Hungarian Ferenc Sido. Hungary had dominated the sport in the early part of the twentieth century. But that would soon change. In the remaining video of their match, Rong looks almost casual. He stands flatfooted. He wears long pants and a polo shirt:

Rong came back to China a hero. The hours he had spent alone serving across the ping-pong table in the breakroom at work had paid off. By defeating Sido, he became the first Chinese world champion in any sport. He became a walking piece of propaganda. He was greeted by Mao Zedong and became a zealous communist. China’s first table tennis supply company opened after his victory and called itself Double Happiness. The first Happiness was Rong’s victory in Dortmund, which coincided with the second Happiness: the tenth anniversary of Mao’s 1949 establishment of the People’s Republic of China.

Table tennis flourished in China after Rong’s victory. Rong was named coach of the women’s national team. He got married and had a daughter. It seemed as if his decision to leave Hong Kong behind had paid off. His teammate Zhuang Zedong won the next three men’s singles titles. Zhuang would go on to international renown as the Chinese face of Ping-Pong Diplomacy after striking up a friendship with American player Glenn Cowan at the 1971 World Championships in Japan.

Rong did not become famous like Zhuang Zedong. He did not live to see China’s global dominance in table tennis come to fruition. Nor did he live to see the techniques he himself had helped develop evolve into fundamentals used by millions of players around the world.

In the mid-sixties, some table tennis players became targets of Mao’s Cultural Revolution. The national team was disbanded. “At the time I worried about him,” wrote Rong’s childhood friend Steven Cheung. “...I understood how the Red Guards felt about property. Table tennis skill is a kind of property, and I wondered what would happen to Rong.”

In 1968, three members of the national team were placed under house arrest: all three men had come to China from Hong Kong. Together, the trio had helped build the People’s Republic into a superpower in the sport. In April, Fu Qifang hanged himself in the national team locker room. Fu was the head coach of the men’s national team. A month later, Jiang Yongning hanged himself in his dorm room. Both men had been accused of spying by Mao’s Red Guard.

Rong was also accused. On June 20, 1968, only nine years after Dortmund, he strung a jump rope over the branches of an elm tree. The writer Keane Shum compiled a list of his alleged crimes. “That he loved reading Western novels, that he enjoyed listening to classical music, and that he missed Hong Kong.”

Rong Guotuan was found dead with a note in his pocket. He was thirty years old.

I am not a spy; please do not suspect me. I have let you down. I treasure my reputation more than my life.

Related Reading

I came across the the story of Rong Guotuan in the spring of 2014, when I was reading everything I could get my hands on about table tennis in preparation for writing this feature for Deadspin. Rong’s story didn’t really fit into that piece, but in the five years since I published it, I’ve thought about Rong often. His life just struck me as a perfect metaphor for the absurd and tragic nature of history. It’s also a pretty stark reminder (not that we need one these days) that despite what some people might say, sports are deeply political.

As I researched and wrote this, I kept wishing I knew more about Chinese history, and about China’s relationship with Hong Kong. But the more I read about that relationship, the less I feel like I understand. If anybody has anything they recommend, please feel free to reply to send them along to enusbaum@gmail.com.

For more about Rong, I recommend Nicholas Griffin’s fascinating book, Ping-Pong Diplomacy (of which Rong is only a small part), Keane Shum’s essay about Rong A Great Leap Forward from issue 53 of the Griffith Review, and Steven Cheung’s remembrance of his friend.

For only marginally related joy, I recommend this very extensive website featuring photos of celebrities playing table tennis.

Penhold vs. Shakehands

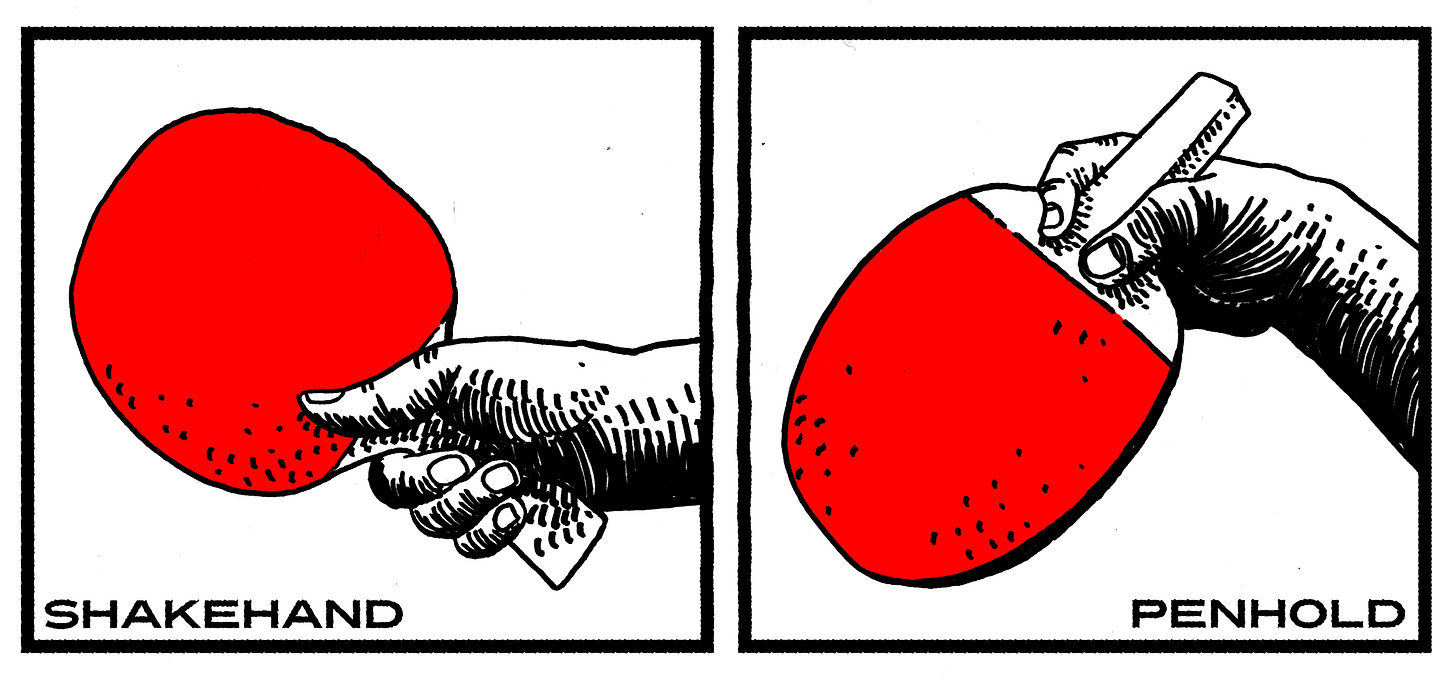

At the start of this newsletter, I referred to Rong’s penhold grip. If you’ve ever played ping-pong, you probably picked up the paddle and held it like a tennis racket. This is called the shakehands grip. Literally, you hold the paddle like you are shaking hands with it. Rong’s penhold grip is also what it sounds like. Hold the paddle like a pen. With the shakehands grip the tip of the paddle points upward out of your hand, and with the penhold it points downward. The shakehands grip developed in Europe, and the penhold grip developed in Asia. Each grip comes with its own advantages and disadvantages. To get a better sense of them, I spoke to Sean O’Neill, who spent a dozen years playing for the U.S. National Team, and now serves as their director of high performance.

Shakehands is easier to learn. It’s easier to hit an effective backhand, and play an strong power game. This advantage has only been exacerbated as the sport has evolved. In the last two decades, table tennis has gone from a 38mm celluloid ball to a 40mm plastic ball, slowing play down and making it more tennis-like. With the shakehands grip, O’Neill told me, “you can just go out there and play like Federer.”

Penhold gives you an advantage on the serve — it makes it easier to mask your spin. It also helps in short play, and opens the paddle up for a more naturally dominant forehand. But historically, it also diminishes the backhand. Until recently, penhold players typically only used one side of their paddle for their forehand and their backhand.

While China has dominated the last forty years of international play in table tennis playing penhold, the grip has slowly diminished. Even some great Chinese players, like 2016 Rio Olympics Gold Medalist Ma Long, play shakehands now. At one point, it seemed like the penhold grip was going to be relegated to history. Then came Liu Guoliang.

In the 1990s, Guoliang became only the second player to win a table tennis grand slam: gold medals in the World Championship, the Olympics, and the World Cup. He did it with what became known as the Reverse Penhold Backhand. Where traditional penholders only used one side of the paddle, Guoliang developed a technique to flip the paddle on the backhand, and use the opposite side. In doing so, he solved the penhold’s greatest weakness: the backhand attack, and breathed new life into the grip.

Now Guoliang is the coach of the Chinese men’s team. And the great hope of the penhold grip is Xu Xin. In our conversation, O’Neill compared Xin to both Kareem Abdul-Jabar (his shots are unstoppable like the sky hook), and Michael Vick (he’s an athletic lefty who will drop your jaw with his talent). So that’s the note we’ll leave you on. Here’s eight minutes of Xu Xin, ping-pong’s most exciting talent, and the greatest current user of the penhold grip that Rong Guotuan mastered in that union hall in Hong Kong:

This has been Vol. 1 of Sports Stories, a weekly newsletter about sports, history, and sports history by Eric Nusbaum (words) and Adam Villacin (art). If you have any questions, comments, or concerns, please contact enusbaum@gmail.com. We’d love to hear from you.