Final Destinations

We wrap up March with the tales of daring women aviators in Turkey, Russia, and Egypt

Welcome to Sports Stories, a publication at the intersection of sports and history: written by Eric Nusbaum, illustrated by Adam Villacin, and delivered to your inbox every Tuesday. If you’re not already a subscriber, please sign up here—it’s free!

This month at Sports Stories, we’ve been covering early women in aviation. It’s been fascinating to dive deep into this history, to linger and to look at it from multiple angles, as opposed to the, ahem, fly-bys that we often do here. We could have kept going and going.

But March is nearly over, and the rest of the wide world of sports is calling. Today we’ll wrap up this project by running down the bios of some of the women we missed. In particular, we’ll look at early women fighter pilots. It didn’t take long for the airplane to evolve from a pipe dream to a novelty, then from a novelty to a serious weapon. (This probably says something about our society at large.) Nor did it take long for women pilots to become women fighter pilots.

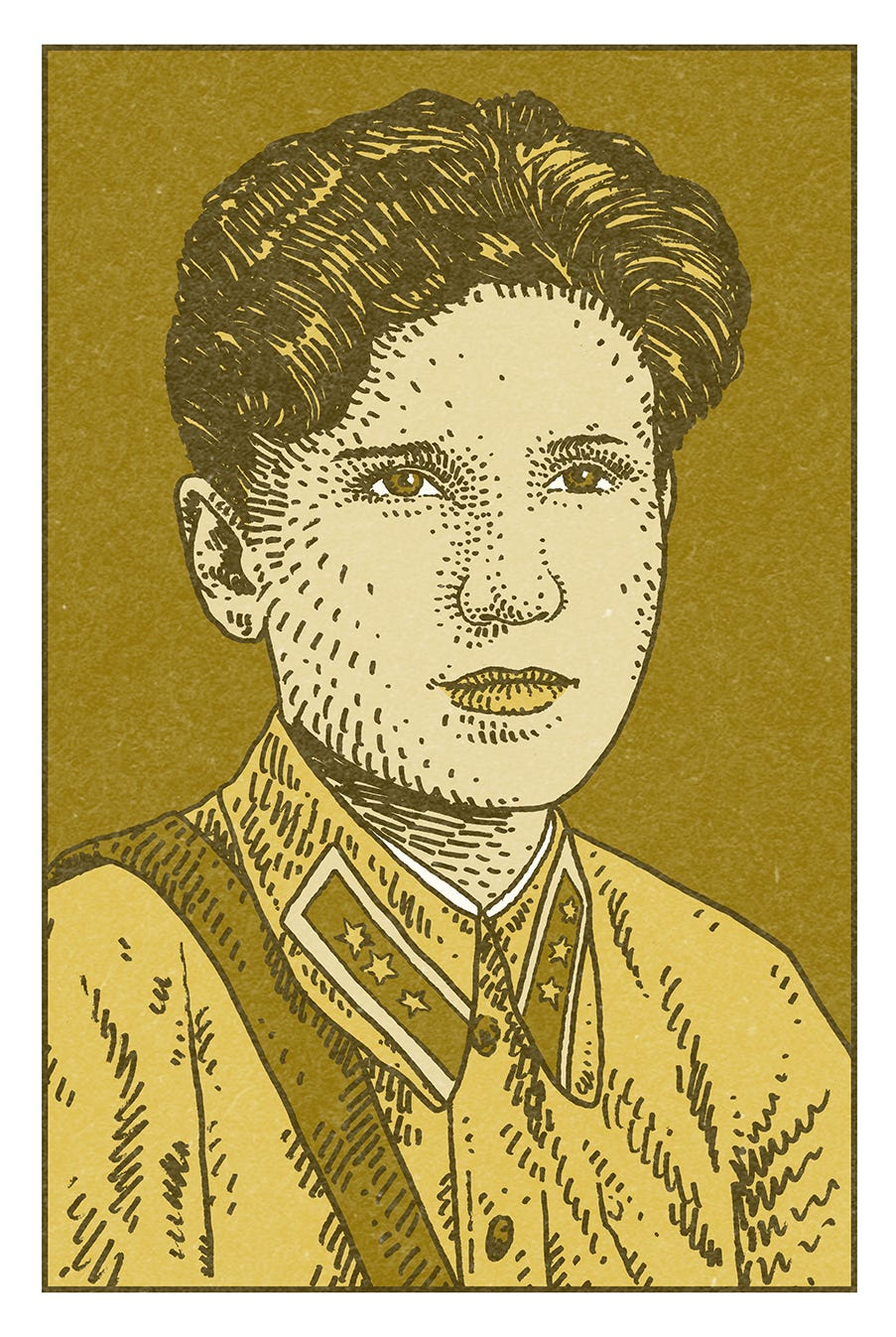

The widely acknowledged (and Guinness Book approved) consensus first women fighter pilot was Sabiha Gökçen. Gökçen was the adopted daughter of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey, and it was through him that she was admitted first to a parachuting school, and then to flight school. She once said that to test her willingness to risk her life as a fighter pilot, Ataturk himself pressed the barrel of a gun to her temple and pulled the trigger. Gökçen did not flinch. The gun was empty. Her achievements in combat were widely celebrated in the 1930s and 40s. But among her missions was the bombing of the Kurdish province of Dersim in 1937.

The Dersim campaign was framed in Turkey at the time as being a triumph—a rebellion successfully squelched. But in the intervening years, evidence has come to light that the rebellion was a pretext for a planned massacre. Gökçen was a symbol of Ataturk’s secular Turkey, where women’s rights were dramatically expanded. But she has also become a symbol of Ataturk’s genocidal legacy. A few years after her death in 2001, a Turkish-Armenian woman claimed in an interview that Gökçen was in fact of Armenian ancestry herself, setting off a years-long national controversy. The journalist who wrote the story, Hrant Dink had spent his entire career writing about the Armenian Genocide, and advocating reconcilliation. In 2007, he was assassinated on a sidewalk in Istanbul.

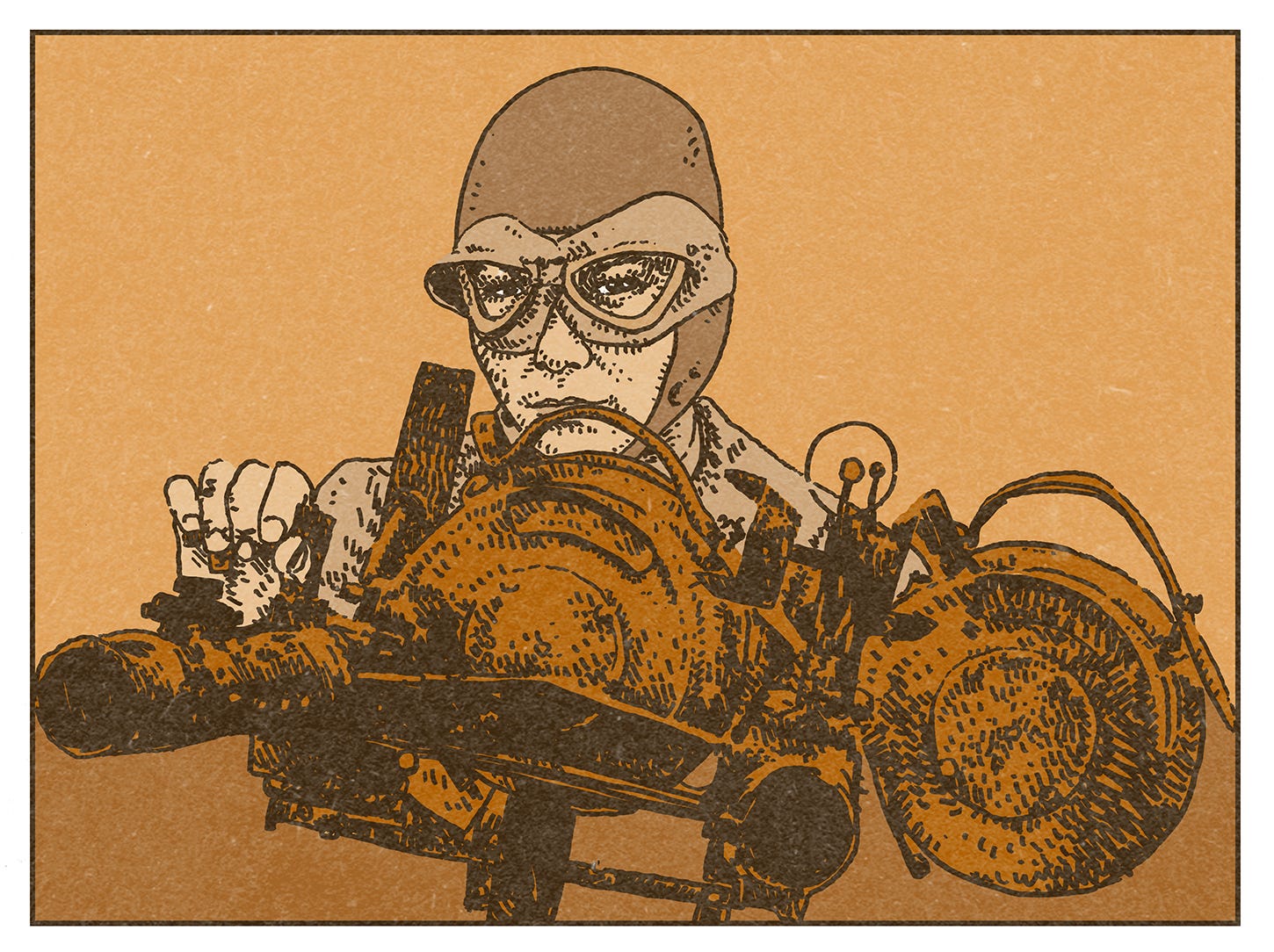

During Gökçen’s rise to fame, she was sent for training in the Soviet Union, which was quick to embrace women aviators. In fact, one of the USSR’s early aviation heroes was Marina Raskova. Raskova’s father was an opera singer who died in a motorcycle crash, and her life was an opera unto itself. She was training to follow in her father’s footsteps and on her way to opera stardom when a bad ear infection derailed her singing career. Instead, she became a chemist, a draftswoman, an air force navigator, and ultimately a famous pilot.

Raskova’s fame led to a close relationship with Joseph Stalin. During World War II, Raskova was able to use her influence to convince Stalin to allow her to start a series of all-women air regiments: two bombing groups, and another of fighter pilots, the 586th Fighter Aviation Regiment. The 25 pilots who comprised the 586th flew important missions, including at Stalingrad, but two pilots in particular became legendary. In particular, they became flying aces. (I recently learned that flying ace is a technical term for a fighter pilot who has shot down five or more enemy planes.)

Like Raskova, Lydia Litvyak and Yekaterina Budanova both lost their fathers at a young age. Litvyak, who grew up in Moscow, was a teenager when her father was arrested as an enemy of the people. Nobody ever saw him again. Budanova’s father died when she was young, forcing her out of school at a young age to begin to work. Her mother sent her from her village to live in Moscow, where she worked as a carpenter at an airplane factory.

Litvyak and Budanova both enlisted in the 586th in 1941. By the summer of 1942 as the Battle of Stalingrad lingered on and the supply of male pilots dwindled, the pair became a regular fixture of the Soviet defense. Litvyak, in particular, became a celebrity, known as the White Lily of Stalingrad. She would buzz over air bases and perform aerobatics after completing missions. Both pilots would soon be reassigned from the 586th to a unit known as the 9th Guards Fighter Aviation Regiment. The 9th Guards were a sort of supergroup, compiled of the USSR’s top pilots with the express purpose of defeating the Luftwaffe.

In July of 1943, Budanova was flying an escort mission in Ukraine when she was met by three German fighters. After a prolonged dogfight, she was hit with machine gun fire. Budanova was able to land her plane in a rural field, but by the time civilians on the ground were able to reach it, she was dead.

Less than two weeks later, Litvyak died in a similar fashion—overcome by German fighters in a dogfight over Ukraine. One of her colleagues said he saw her plane through a cloud, and then she was gone. No sign of a crash. No sign of anything.

Budanova was 26 years old. Litvyak was 21.

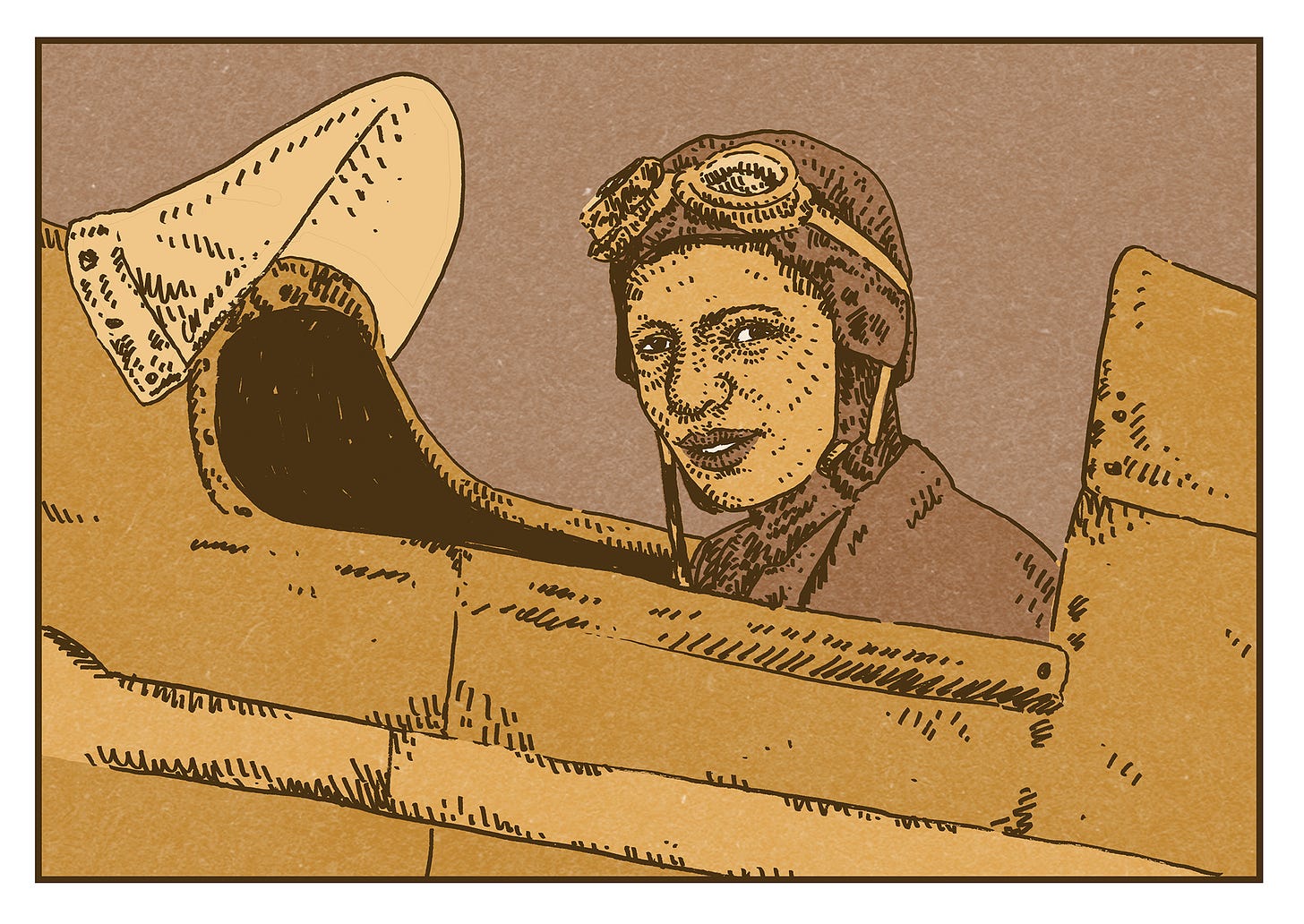

Lotfia Elnadi became a pilot at about the same time as Budanova, Litvyak, and Gökçen. But unlike them, her flying career was a totally civilian endeavor. Elnadi was born in Cairo in 1907 to a middle-class family. Her father was a government official and her mother encouraged her to pursue her education at the American College in Cairo. There she came across an article about a new flying school in Cairo. Just a teenager, she was met with resistance at first. Knowing that her father would not approve of flying lessons, she first turned to the article’s author about helping enroll her at the school. When he refused, she reached out to the director of EgyptAir. He saw a PR opportunity.

Elnadi was set up at the flight school, where she worked in the office to cover the costs of her lessons. In 1933, she became the first woman to earn a pilot’s license in the Arab world, as well as in Africa. The first passenger she took up in the air was her father, who had initially objected to her learning to fly. He was nervous at first. “He knew that if we crashed, we would crash together, so he relaxed and began to enjoy the flight,” she said later in life.

Elnadi competed in air races and was given a plane of her own by the King of Egypt. A number of women in Egypt followed in her tailwind and became pilots themselves. But Elnadi’s career was relatively short. She suffered a fall (on the ground), and injured her spine, that prevented her from flying. She lived in Switzerland, Toronto, and ultimately back in Cairo, where she died in 2002. She was 95.