"Hail Mary," Full of Grit

A conversation with Britni de la Cretaz, co-author of an awesome new book about women's pro football.

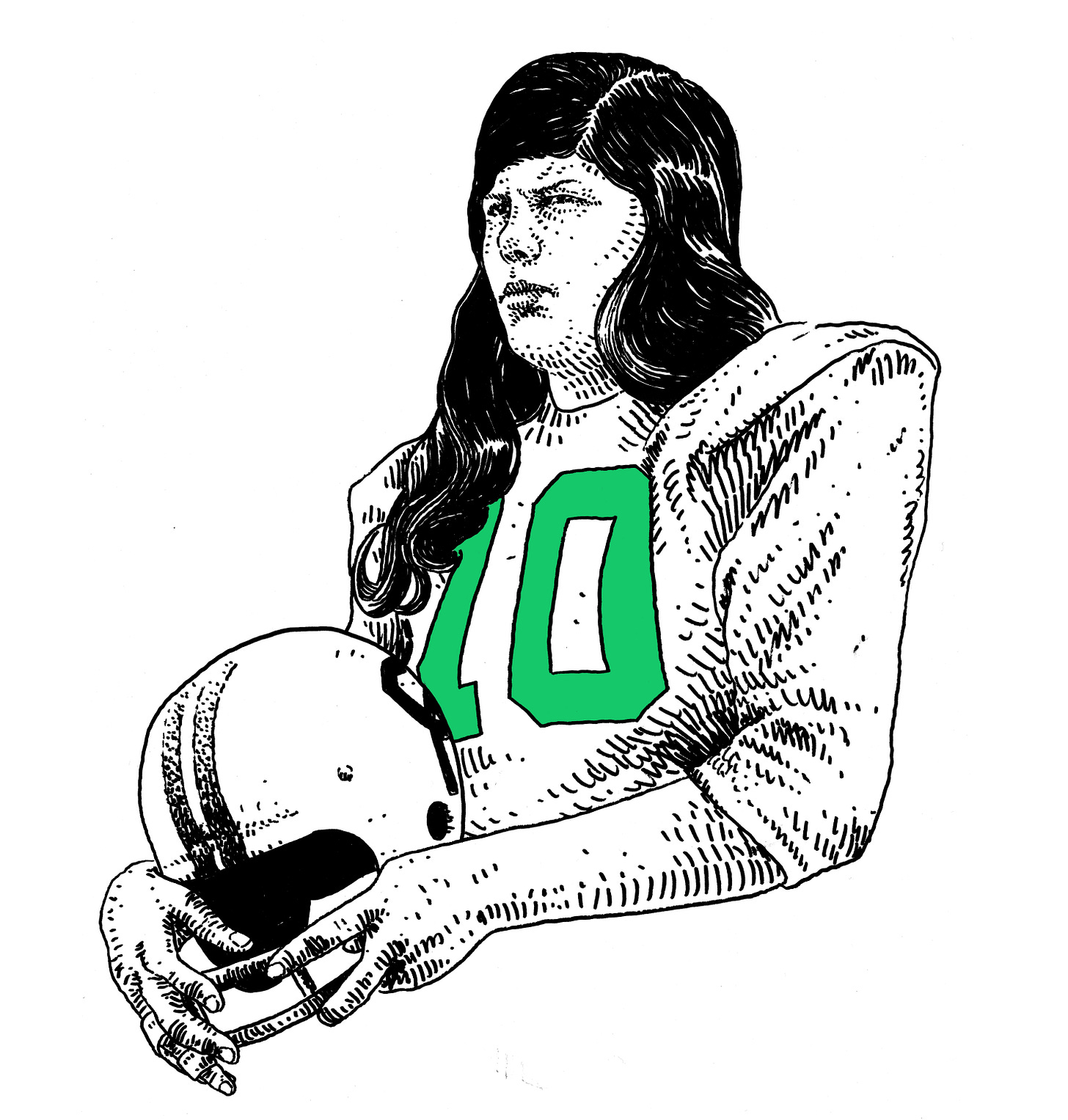

The July 28, 1974 edition of the Sunday Magazine published by the Columbus Dispatch newspaper featured a photo of one of the city’s newest pro athletes: a promising young quarterback staring off into the distance, helmet cradled in her arms. Her name was Lisa Perez. She played for a new team called the Pacesetters, in a new league, the National Women’s Football League.

The story describes Perez as one would any other promising football prospect, complete with a scouting report from her coach:

One future star is 17-year-old quarterback and defensive back Lisa Perez. The five-foot-three, 125-pound quarterback graduated from Whitehall-Yearling High School last spring. “She’s got a lot of natural ability, speed, and quickness,” Knapper explained. “And she’s an outstanding scrambler and a good passer too. The way she’s developing, I’d say she’s a potential all-pro.”

This is all amazing because of a.) how normal it seems and b.) because the fact that for 15-ish years, there was a vibrant women’s professional football league in America is completely unknown to most people. It was unknown to me, before reading an article by a writer named Britni de la Cretaz in 2019 on the Toledo Troopers.

Now Britni has teamed with Lyndsey D’Arcangelo to turn that article into a book called “Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women’s Football League.” This is the kind of subject that we would briefly touch on in Sports Stories -- highlighting Lisa Perez or Sunday Jones, a singer who toured the country with the Ohio Players before giving it up to play wide receiver for the Toledo Troopers -- before telling you to go read something more deeply researched.

Well, this book is deeply researched. It’s also empathetically reported, and entertainingly told. It has, as the internet’s David J. Roth put it in a YouTube interview with the co-authors, a layer of “good-natured 70’s scuzz.” It also has really smart critical analysis from writers I admire. I wanted to know more about it, so I reached out to Britni (who I’ve known for a while), and they were kind enough to indulge me in a conversation about their writing process. The conversation Between Britni and I has been edited and condensed for your sanity.

Let’s talk about where this book came from. It’s about a slice of the history of America and sports that is not talked about, and doesn't even have a faint echo in people's minds -- at least didn't before this. How did that come about? And what did you feel like was your obligation to these women who were writing about?

Initially it was just going to be a book about women in football that Lyndsey and I were going to write together because I was looking for a book like that and it didn’t exist. But I also didn’t know a ton about football and she does. So we had an idea that we could do this together. That first book did not sell. But in the course of researching it, we discovered this league and specifically we discovered it because of the Toledo Troopers, who are the winningest pro football team of all time, men's or women's, or to this day.

I also had a sports column at Longreads. I was just starting it and it was actually very much in the vein of what you do at Sports Stories, where I would go back in history and try to rewrite a narrative that either has been forgotten or erased or was maybe only told from one side. And the first piece that I reported for that was about the Troopers.

I set out to ask what happens when the winningest team loses their first game, and I recreated that loss. And that’s when I realized how rich this material was, and how much material was there. Because you realize there was a whole league, and there were all these teams that played. But you’d Google and there was not even a Wikipedia page for the league. There is now. It was made yesterday by some folks that read the book, which is really cool. But these teams were nowhere. Like, there’s an AngelFire page being kept by some guy and that was it. So I think that’s where we realized that this was the story that needed to be told -- and the players are still alive to be able to tell it to us. So this was the time to do it.

What was it like meeting these players decades after their careers and kind of holding their stories in your hands? I did a book about people who had mostly died, and I felt a tremendous amount of stress and obligation to them, even despite that. I wonder what it would be like to do that with people who were there to read it.

I was really nervous about what people's reaction was going to be. I have not heard anything negative yet. Anyone who's mad at us has not told us. These women have been waiting 40-plus years for someone to ask them about this. They thought they were forgotten. They thought it didn't matter to the world. But it mattered so much to them. Most of them only played a few seasons and may pretty consistently described them as the best years of their life.

Some of the players were afraid to talk to us because they didn't know if we were legit and they didn't want to give such a precious story away to somebody that wasn't going to do justice to it. So I really think about that responsibility. Some of the players who are more accessible because they text or whatever -- I really went back a lot to them. I would say, “Hey, I'm hearing that you told me this. I'm recognizing that this was the time period that it was happening. Would it be a misrepresentation for me to draw this conclusion about your motives?” I really didn't want to put words in people's mouths.

Their job is to tell me their story, but it's my job to make meaning out of that story and to examine it from a larger lens. And I also knew I was taking a story from somebody, right? You lose agency over a story when you give it to somebody else to tell. Lyndsey and I both tried to be as responsible as possible.

We had an excerpt in Sports Illustrated, and Linda Stamps, who was one of the women who founded the Columbus Pacesetters, she's kind of the main character in that excerpt, texted me the day it ran and was just like, “I don't know how to thank you because I'm in Sports Illustrated today as a football player. My childhood dream came true.”

That was such an intense thing to realize how much it means. It’s an enormous responsibility that we both carry with us and take really seriously. Also, I will say, I hope some of these women do get to speak for themselves. We have a list of players who are really happy to do press. And I hope that people will take us up on that and that they'll have the opportunity to share their stories in their own words as well.

What was it like having a co-writer in Lyndsey? Had you done stories that way as a journalist before?

Weirdly I'm co-writing more stuff now. But in general, no. Most of my stuff was just me. Lyndsey was great. We complemented each other really well. The scope of this league is so great. There were so many teams ,and the number of people and the amount of information that you're trying to track down -- I was actually really glad to have her as a person to split it with. I think if I was doing this alone or if she was doing this alone, it would have been a different book because we bring different things to the project. Also it would have taken a lot longer than it did.

But we worked together really well. And I think we also just both really trusted the other person's process and the other person's voice, which allowed us to kind of settle in and do our best work. Lyndsey is a much more structured writer. She writes every day and has worked on the book every day from the day we got our book deal and has never missed a deadline in her journalistic career. I believe deadlines are suggested start dates for your projects and I wrote 20,000 words of the book and the week before it was due to our editor. So we just had wildly different processes and it could have gone really, really wrong. And luckily it did not. And I think that's because we had so much respect for each other as writers.

Lyndsey comes from a fiction background, which I think a lot of people don't know because she's also a sports writer. But so she's written YA fiction books. And so she brought a lot of the character depth and the storytelling chops. And I did a lot of the critical analysis, and also I was the nerd doing a color-coded post-it note visualization of our structure and reading all of the other narrative nonfiction books for ideas on what our should look like and stuff like that. We definitely came from different places, but it all worked really well together.

Did your research and reporting on this book and writing it change your perspective of America in the seventies in particular, and how you thought about the country?

It complicates these very pat understandings that we have. Look back and you'll see Title IX happened in 1972 and the league started in 1974. So the conclusion from many folks is that it was a result of that. Well, no, it wasn't. These teams weren't affiliated with schools. Some of the players who were college students benefited from Title IX because they were maybe on a softball team that was formed because of Title IX, or there were other organized sports that they could play in college that they wouldn't have been able to a few years before that. But if the players were older, that was out of reach to them. And also there's a class-based thing happening here where if there are working class folks or folks who work in the trades, they're not playing sports through those institutions. So that's a place where sure, some of the women are impacted by Title IX, but it had nothing to do with the league and many of the players to this day, when I asked about Title IX, they said, “what's that?”

Or that if you look at the newspaper coverage of the time, journalists really wanted to portray these women as women's libbers because why else would women want to play football? And when you look at some of the few things that have been written about the league, you know, they really paint these women as like feminist activists who are playing during the women's liberation movement. And that narrative is not one that 90% of the women claim for themselves. It felt really irresponsible to shoehorn that and to put those motives in these women's mouths, because at the time they didn't think of themselves that way, and they still, for the most part, don't. Some have come to think of it that way.

What I think it it did for me was it kind of complicated what we think about movements and how they work even like queer liberation, post Stonewall. These women were, you know, in the Rust Belt or the South and Stonewall was not on their radar at all. It’s not that simple. There’s a lot of class and region based analysis that goes into those movements that I think sometimes gets really flattened.

What did you do to unflatten it as you're writing the book? How, how much do you think about portraying politics and injecting that kind of analysis?

I think our solution there was to not put any words in people's mouths and to be really clear about how they formed their own conclusions about what they did and where they stood.

We can also reflect on the ways that change happens in society, and that exists outside of organizing meetings or picket lines. Right? You don't have to think of yourself as an activist to actually be responsible for pushing society forward. All you have to be is somebody who refuses to toe the line or who is willing to do what you're being told that you can't do. And something that all of these women have in common is that they played football at a time when the world told them they absolutely should not be doing that and they could not do it. And so just by playing football, by doing this thing, they love, they actually are taking a stance and creating change.

Those realities can coexist. There's a chapter called “Unwitting Activists” because they may not claim feminism for themselves, but a lot of them were women working in male dominated fields: they were the only women climbing telephone lines, you know, they were their mechanics. These women were the first women to enter the workplace in certain fields. They’re dealing with all of that as well. They don't have to claim feminism for themselves to have been kind of living the politics of “what does it mean to demand more for women or people of a marginalized gender?”

Is there somebody who you wrote about whose story and personality drew you in in an emotional way that kind of went above and beyond your expectations? I know that happens to me as a journalist sometimes.

My most meaningful conversation, and actually the one who has I think become a breakout star based on reader reception so far, is a woman named D.A. Starkey. She played for the Dallas Bluebonnets. She was such a big personality, and she was so open with the way that her queerness and her queer community overlapped with her desire to play football.

She was also just really open about -- she’s 30 years sober now, and I’m in 12-step recovery as well. We talked a lot about that. A lot of that did not make it into the book. But at the time she wasn’t sober, and she’s in these bars a lot, and really unabashed about “I didn’t read a newspaper. I didn’t know what Stonewall was. I didn’t even know there was a football team because I didn’t read the newspaper. Somebody had to tell me.” She's really funny.

I was talking to her and the Bluebonnets team at a time in my life where I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do personally. Shortly into my interviews with the Bluebonnets players, I ended up asking my husband for a divorce, and a lot of it had to do with my conversations that I had with queer elders, and really realizing how badly I wanted them to recognize me as part of the community, and realizing the ways in which my personal life situation rubbed up uncomfortably for me. It was a catalyst for me asking for a divorce, the first two months of starting to report this book. And the players knew that a little bit, because you’re in touch. And they were really lovely, like, “We’ve been out for 50 years, let us tell you about it.”

And I ended up with this really beautiful intergenerational moment. You’re a journalist, right? I didn't expect to develop friendships with these women, but it felt different from the way I source most of my work and the source relationships I have with most of the reporting I do.

Books are different, right? Emotionally for me, it was all-encompassing. I dreamed about my book every night and the people in it. And their lives became deeply intertwined with mine and my family’s lives. It was very immersive. It sounds like you had that experience too -- and in even more profound ways than I did.

I had pictures of the women on my wall as I wrote. It’s really important to remember who you're writing for and why. And then they're so excited to have their story told and you're getting texts from them when they remember something or even jus they're sending me newspaper clippings about girls playing football. They're still sending me their NFL predictions every Sunday, and I haven't been able to tell them I don't watch football, because they're so excited to connect about that. One of the women sent Lyndsey care packages of snacks while Lyndsey was writing.

It was very different from the way I usually think about sourcing. And plus you have to go back. There's some women that we talked to once, and that was all we were going to get, you know? And there are some that were really, really involved. The ones that would answer text messages and go through really specific details and get on the phone with you whenever you needed to. It really felt like there were partners in the work in some ways.

Thanks for reading Sports Stories. We’ll see you next week.