"I am the Same Ralph Metcalfe"

Even before he ran for office, Ralph Metcalfe's Olympic career was marked by politics

Welcome to Sports Stories, an illustrated newsletter at the intersection of sports and history. If you’re not already a subscriber, please consider joining up here.

If you’re a longtime reader, or just enjoy this post, please consider doing us the favor of sharing Sports Stories. You are the reason we do this, and also happen to be our best (and only) marketing system.

In many parts of the country, including where I live, today is Election Day. Despite the fact that our democracy is clearly broken, corrupted, and somehow getting worse every day, I still love voting in a sincere and corny way. I can’t help it. I want to believe. This week’s Sports Stories is about an athlete-turned-politician. It’s about the good things that can happen in America, and also the bad things that give the good ones their shape.

Ralph Metcalfe was born in Georgia in 1910, but he was a little boy when his family moved to the South Side of Chicago. That’s where he grew up. The son of a stockyard worker and a seamstress. In high school, Ralph started running track. His coach told him that as a Black man he had to be more than just faster, he had to put actual daylight between himself and his competition. Metcalfe did that.

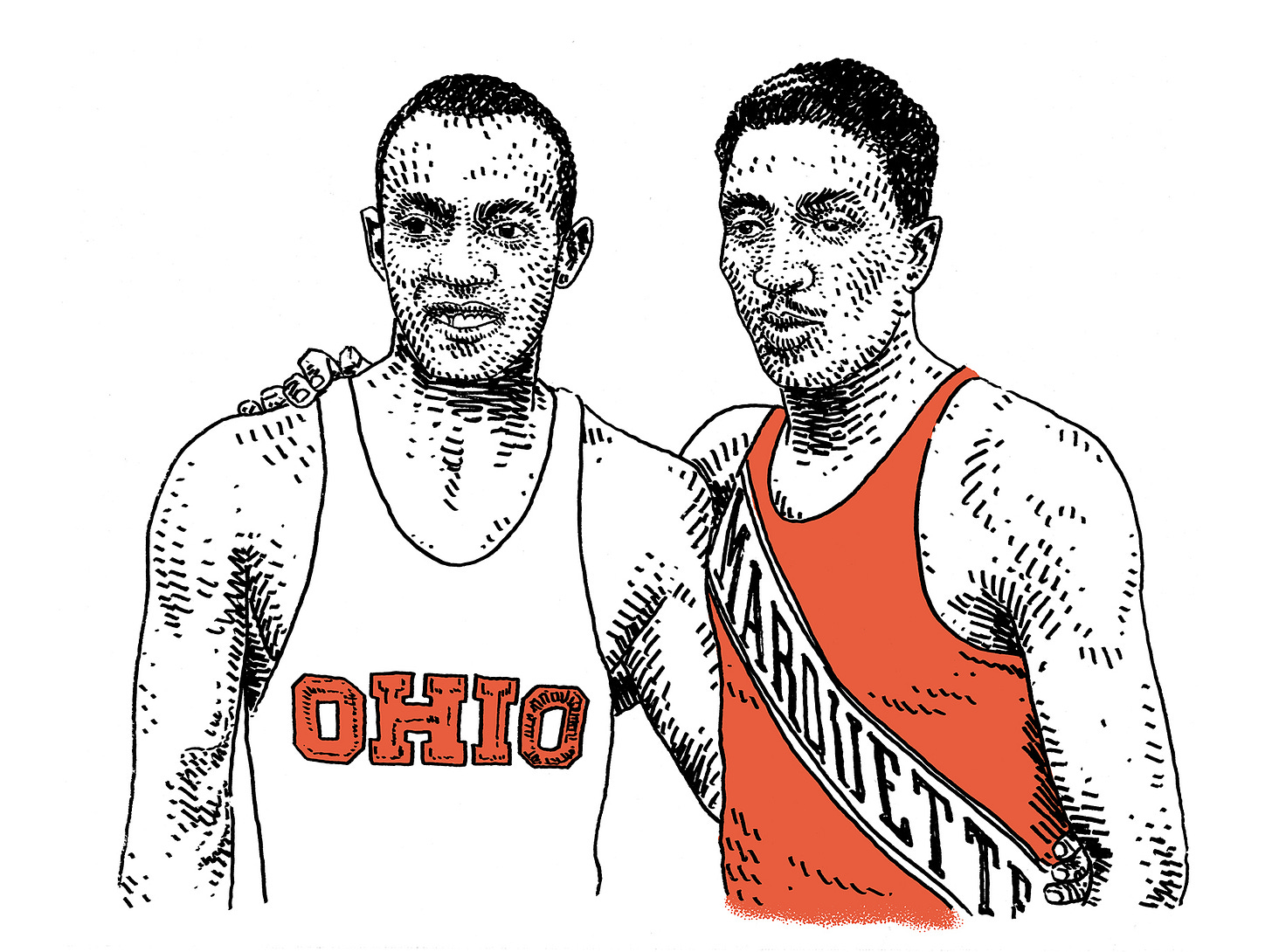

He ran all the way to the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles, and straight into the finals of the 100M sprint at the brand new Memorial Coliseum. It was a close race. As close as they get. Metcalfe appeared to cross the finish line at the exact same moment as his teammate Eddie Tolan. It was quite literally a photo finish. And the judges examined the photo for what seemed like hours before finally awarding the gold medal to Tolan.

The photo they used was by no means definitive. And video recordings appear to show Metcalfe crossing first. But it didn’t matter. A few days later, Metcalfe finished behind Tolan again in the 200M. This time, he finished third. After the race, Metcalf insisted he had been running in an improperly measured lane that was in fact at least two meters too long. But it was too late.

Metcalfe never really believed that he had lost fair and square in either race. But he wore the defeats gracefully. He went back to school at Marquette University (where he also converted to Catholicism) and waited for his next turn at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. That time, his principal competition was another teammate: Jesse Owens. Once again, Metcalfe found himself in second place in the 100M. Then, in the 200M, he finished third behind Owens and Mack Robinson (the older brother of Jackie).

That should have been it for Ralph Metcalfe’s Olympic career: three silver medals and a bronze: a legacy to be proud of. But then, two days before the 4x100M relay, the American track coaches decided to make a change to their lineup. Two racers, Sam Stoller and Marty Glickman were dropped from the team. Their replacements would be Jesse Owens and Ralph Metcalfe.

At the time, American coaches argued that the changes were made to give the American team its best chance to win. But Stoller and Glickman were fast -- and they had been brought to Berlin specifically to compete in this race. Everybody knew the real reason they had been dropped. It was because they were Jewish.

Avery Brundage, the head of the U.S. Olympic Committee, was a known anti-Semite. So was American track coach Dean Cromwell. They were approached by Nazi officials via backchannels officials to remove he Jewish sprinters -- so they did. Metcalfe and Owens argued that this was unfair, but were not in a position to do much about it.

“I resented the fact that they left two Jewish boys off the team, Sam Stoller and Marty Glickman, in order to satisfy the Nazi people over there,” Metcalfe said years later. “It was our team. We were not supposed to have Germany dictate to us, nor their philosophy, nor their politics dictate to us.”

But this was how Metcalfe won his gold medal. And this was the experience he brought with him back to the United States after the games. He taught at Xavier University in New Orleans and coached the track team. He served in the Army in World War II and became an officer. Then he went back home to Chicago, where he quickly got involved in electoral politics.

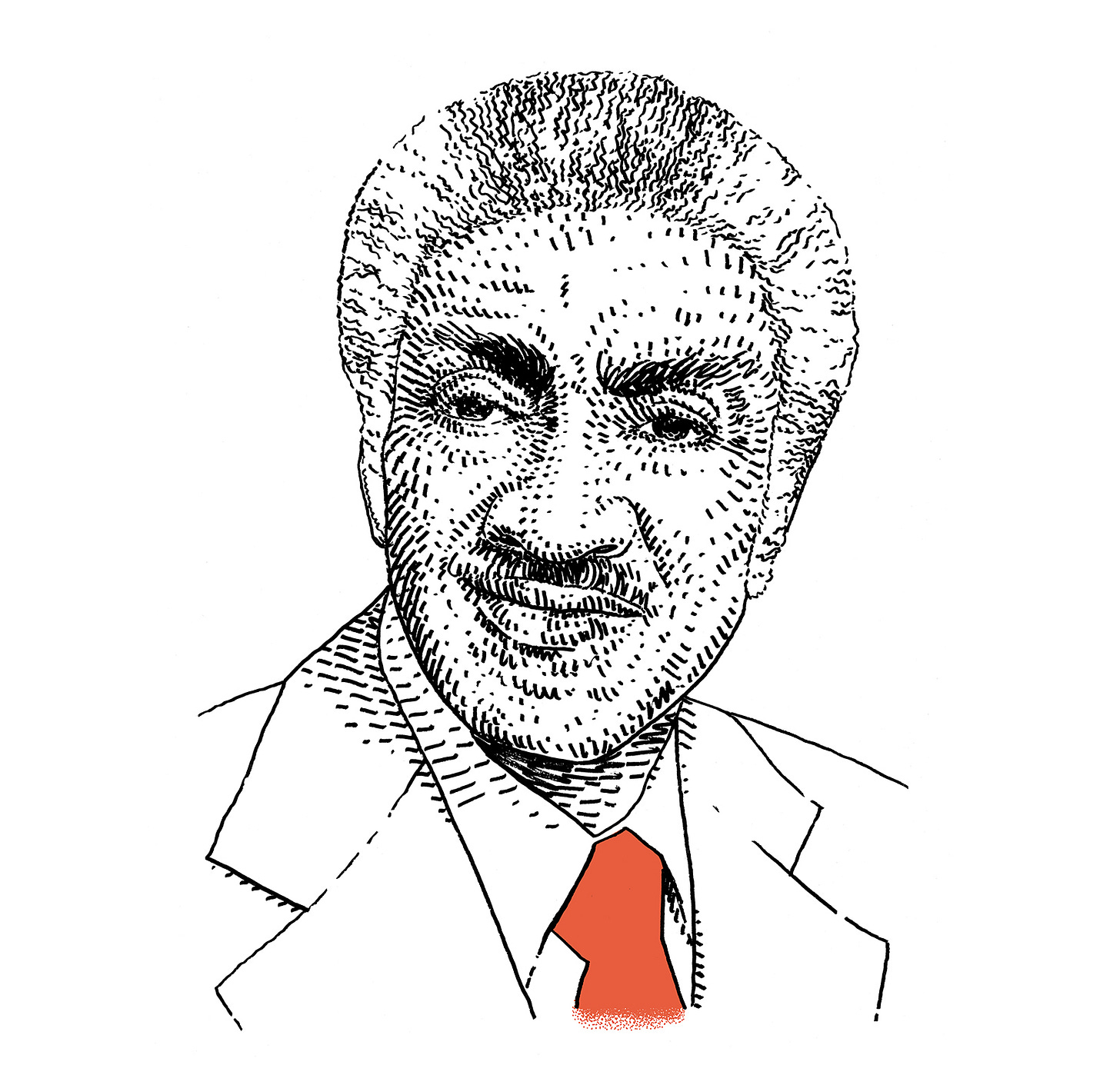

Metcalfe was elected to his local Democratic committee in 1952. Three years later, he ran for alderman and won. Soon, he became a key cog in the political machine of all powerful Mayor Richard Daley. He was a status quo moderate Democrat. This was where things stood until 1970 when he ran for an open seat in congress -- and with Daley’s backing, easily won.

Metcalfe could have been a yes man in congress and continued to do Daley’s bidding. It would have been easy. But that wasn't what happened. In his first year in office, he became one of the founding members of the Congressional Black Caucus. In his second, he broke with the political machine that had supported his career for decades.

It was an ugly and bitter split. Metcalfe came to believe that the Daley administration was intentionally ignoring racist police violence in the city -- and thus tacitly endorsing it. Metcalfe had power and he decided to use it. He called for the resignation of the Chicago police superintendent and his staff. He became, for the first time in his career, an activist, using his office to hold hearings and his platform to draw media attention to the issue. It was a risky turn in what had been a fairly cautious career.

"I know the political realities of what I'm doing,” Metcalfe said at the time. “I'm willing to pay whatever political consequences I have to, but frankly I don't think there will be any.”

Daley stripped Metcalfe of his position in the local Democratic party, and ran a candidate against him in his 1974 primary. But those moves only crystallized Metcalfe’s position, and the feud with Daley only strengthened his resolve. He spoke out against the Daley machine, joined forces with the Rev. Jesse Jackson, and began to reframe his career in terms of civil rights.

“I am the same Ralph Metcalfe,” he told the Chicago Tribune in 1976. “The only difference is that I no longer represent the 3rd Ward and the 1st Congressional District but all oppressed people.”

Metcalfe died suddenly in 1978 of a sudden heart attack while back home in Chicago during a congressional recess. He was 68 years old.

“I think it’s God’s will that I never won an individual gold medal,” Metcalfe said in an interview late in his life. “I make no apologies for that. It’s great experience, it’s good training, it prepares you for life. I think it prepared me well. I wonder what would have happened if I had won all four gold medals. I don’t think it would have changed, but it may have. I don’t think so. But I think losing made me a bigger person and helped me to face the realities of life.”

Related Reading

Ralph Metcalfe’s official congressional biography is actually surprisingly thorough, and even includes references. There are also lots of newspaper clippings out there from both his track career and his political career. I thought this New York Times story from the campaign trail in 1975 was insightful, as was this 1991 Chicago Tribune piece about the sons of Metcalfe and Daley burying the hatchet on the feud. I also enjoyed this interview between the writers Karen Johnson and Tim Neary in the Religion in American History blog.

Finally, there is incredible footage of Metcalfe in the Olympics in this video clip, backed up with some really great interviews with him. I wish I could tell you what the source documentary is, but I cannot:

Thanks for reading Sports Stories. We’ll see you next week.