We tend to think of pro sports and fandom as a collective thing: we watch our favorite teams together. We cheer for our cities. We bond. Together, our voices rise to a deafening volume or, as they are doing right now, they fall into shocked, paralyzed silence.

But sports are also deeply personal. There’s something about sports that creates an intimacy between players and spectators that defies any kind of logic or theory or explanation. If you’re heart is open to the possibility, the greatest athletes can make you feel things just by performing their craft. When a great athlete is at their peak, they are vulnerable, they are volatile. It’s a transcendent thing.

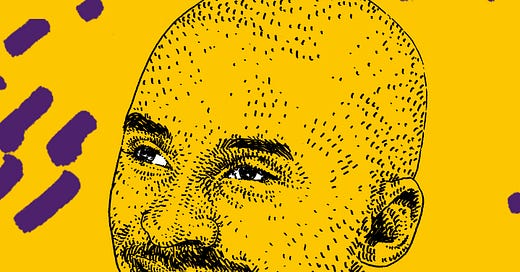

No athlete in my lifetime made people feel like Kobe Bryant. Kobe had the capacity to create this visceral reaction in people just by being himself. How he played. How he walked. How he stuck out his bottom lip on the court. He had the most passionate, incoherent fans of any athlete I have ever seen, and he had the most passionate, incoherent haters. When you watched him play, he gave you something.

Kobe made his debut when I was 10 years old. Growing up in LA -- as Adam and I both did -- during Kobe’s career was a blessing. We got to watch him play every night, and he gave us a lot. He gave us everything he could give. It’s hard to imagine a version of the city without his presence. Then again, it’s hard to imagine that in death his presence will do anything but grow; it’s hard to imagine that in death, his legend will do anything but deepen.

For some reason, when I first heard that he died, I thought back to Kobe’s rookie year. In particular, I thought about the way that particular Lakers season ended. Kobe was just a kid then. He was a teenage reserve, getting acclimated on a team that featured Shaq and Eddie Jones and Nick Van Exel. He was still coming into himself: he hadn’t found his game and grown his hair out yet, and he was still a long way from shaving it off and cultivating the stern basketball monkhood vibe that would come to define the second half of his career.

It was a good Lakers team, but not a great one. They won 56 games. But they had been beaten up and down by an even better Jazz team and looked to be on their way home in the second round of the playoffs. Facing elimination late in Game Five of the series, Lakers coach Del Harris decided to put the ball in the teenager’s hands. I remember sitting at a since-closed restaurant called Backstop Pizza -- kind of a sports bar but for kids, with arcade games and pitchers of soda -- and watching it unfold on a dozen TV screens.

Kobe ended his rookie season by throwing up four airballs in about five minutes at the end of regulation and in overtime. What was amazing about it at the time, and remains amazing about it now is that his body language did not change. Kobe let go of each shot as if he was sure he was about to change the course of basketball history. (Which he was). He let go of each shot with the confidence of a thousand normal human beings. And as each shot fell brutally, painfully, short, he simply kept playing.

This was the first time Kobe Bryant made me feel something. I felt for him. I related to him. And through it all, I admired him. This was, I think, Kobe’s greatest gift. He was obviously one of the best basketball players who ever lived. But more than that, he had room inside him for everyone. He had the capacity to move us.

Tragically, it seemed as if Kobe’s daughter Gianna had that capacity too. They were on their way to a basketball game when the helicopter crashed. Kobe won’t get to watch her grow up and see himself in her. Neither will her mother Vanessa, or Gianna’s three sisters. Each victim on that helicopter has a story. Each of those stories is a tragedy. Adam and I were kids in LA when Kobe entered our lives. Now we’re both fathers like he was.

Maybe this is why Kobe Bryant’s death hits so hard. Not because he was a “hero” or larger than life, or beyond scrutiny. He certainly wasn’t: he was a complicated person who left a complicated legacy that deserves to be considered in its entirety, including the rape accusation and trial in Colorado. Kobe’s death hits hard because his life on court and off -- knotty and brutal as it was glamorous and brilliant-- was so closely tied to our own fragile lives.

He gave all of himself to the people who watched him play basketball. It was a gift to love him and a gift to hate him. He gave all of himself to his family. And now his family is shattered. His daughter is gone. And Kobe is gone.