Welcome to Sports Stories, an illustrated newsletter at the intersection of sports and history. If you’re not already a subscriber, please consider joining up here — we have both free and paid options.

In the fall of 2014, my wife and I had just moved back to LA after a couple years in Mexico City. She was starting a Ph.D. program at UCLA, and I was working as an editor at Vice. I hadn’t lived in LA, my hometown, since the end of high school. It was nice to be home. But I also quickly realized that I was missing something. I was craving a writing community.

So I did what a lot of people do: I signed up for an adult education class, specifically a fiction workshop through UCLA extension. To get into the class, I had to submit a portfolio of short stories, which was slightly daunting because I had recently been simultaneously rejected by ten MFA programs.

Anyway, I got in. And what I got was so much better than any MFA program could offer, because I got Lou Mathews as a teacher. The first thing Lou wrote to me was this:

“You only made one mistake on your application. You addressed me as Professor Mathews.”

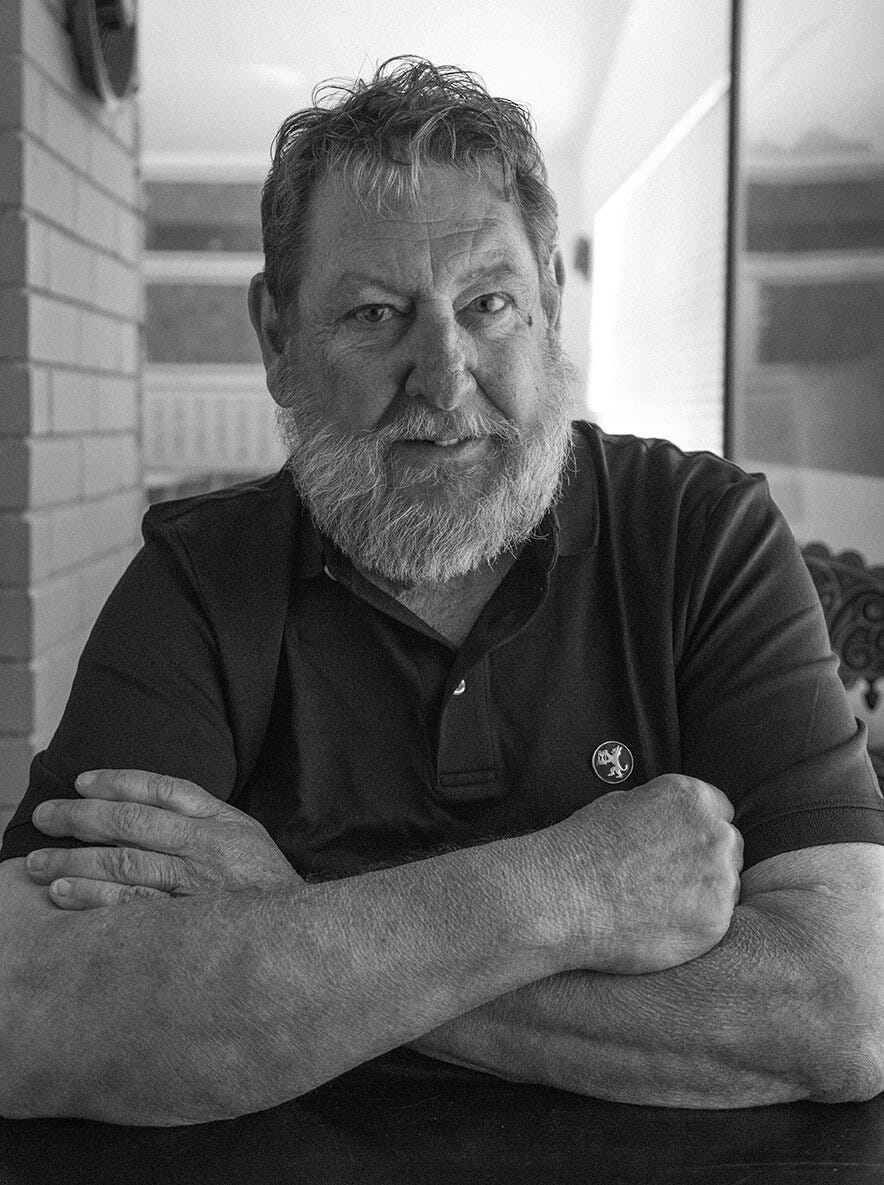

He was right. “Professor” would have been the wrong word for Lou Mathews. He’s a first name kind of guy, as generous with his time, wisdom, and spirit as anybody I’ve ever met. His family has become part of mine, and what I’ve learned from him — primarily how to not just put stuff down, but to actually tell stories — has made me a far better writer, though even that is oversimplifying. It’s safe to say that my book would have been far more boring without him, and it’s safe to say that this newsletter would too.

In addition to all that, Lou is a beautiful writer himself who chronicles the weirdos and working folks of LA as lovingly and honestly as anyone ever has. This makes sense, because Lou is one of those people. Before he became a writer and a teacher, he was a mechanic and a street racer. His first book, LA Breakdown, is set in that world. His second, Shaky Town, was just published last month. You should really, really check it out. I implore you.

In honor of Shaky Town, we’re handing the bulk of this week’s newsletter over to Lou. Here’s an excerpt from an essay of his on street racing originally published in the lit journal Black Clock, followed by a short Q&A with the man himself.

From “Racing in the Streets” by Lou Mathews

In 1965 and part of 1966 I made a good portion of my income on the streets of Los Angeles. Sometimes from straight-up racing but mainly from betting on illegal street-racing. It was a dangerous sport. I saw two engines explode, piston rods punching through the side of the block from detonation because the drivers had loaded their tanks with nitromethane fuel. I saw three cars burn to the ground. I probably saw somebody die. We were running ninety the other way when a car rolled on a back street in Pacoima to avoid a roadblock and the cops.

At that moment in California Car Culture, street-racing was a 24/7 operation. There were more than forty drive-ins across the Los Angeles basin, twelve legal dragstrips. Even 104-octane White Pump Chevron gasoline was only 25.9 cents a gallon. You could cruise sixty miles in a night for about a buck. The cars were overpowered, underbraked, and handled curves about as well as a coffin on a 2x4 skateboard.

My street-racing mentor, a term he would sneer at, was a guy named Charlie Cooney. He was from North Carolina, originally, a tall man when he wasn’t, characteristically, slumped. He was broad, pot-bellied, lazy-looking, except for lively brown eyes and a neat goatee that offset his soft features. Charlie ran a one-man garage on a desolate stretch of San Fernando Road opposite the train yards. It was as close to a shade-tree garage as you could find in an industrial wasteland. He always had three or four cars on jack-stands or cinderblocks, awaiting parts or inspiration. Usually a couple clunkers for sale — AS IS. In back of the quonset hut garage building was a yard where the better cars and parts were kept, enclosed by a chain-link fence and guarded by two Shetland pony-sized German Shepherds. Cooney was a thief and he protected what was his with vigor.

Out front on the sidewalk was a sandwich-board sign:

Batteries — New or Used

Battery Repair & Reconditioning

Batteries were Cooney’s main thing, the neighborhood depended on him for reliable starting power and his prices were fair to startling, five to ten dollars under Pep Boys or Western Auto for brand new batteries. No one could figure out how he made a profit.

Cooney had a simple and ingenious supply method. Late nights and early mornings, he would cruise middle-class neighborhoods far from his own. He’d pick any car parked on the street, write down the license number and the address it was parked in front of, jack the hood, and steal the battery. It was simple work, if the terminals were corroded, he’d cut the cables with shears and lift out the assembly. He didn’t care about the condition of the battery. He brought them back, sometimes ten a night, to his shop, where he would wash them down with baking soda, flush them, add new battery acid, recharge them, and wait a week or so. He would retrace his route, assured that each car would have a new battery. He’d pull the new battery out, put the reconditioned battery in and drive off with the new inventory. He assumed that most car owners never knew about the switch. No reason to lift the hood if the car started.

My high school, Peter Noster, was a couple miles from his shop. I met Cooney delivering parts for a local NAPA auto parts store and saw him nightly at the local drive-in, Van De Kamp’s, which was Street-Race central. I was an agreeable young fool, willing to run errands, and I was always there, hanging out. Cooney decided he liked me or that I could be useful and took me in hand.

Cooney had four loves: Olympia beer, Lucky Strike cigarettes, the chile verde burritos at Lupitas down the block from his garage, and street racing.

He taught me about the world of street racing. There wasn’t an ounce of romance in his soul, street racing was his livelihood. His scams and weekly work were only the capital he needed to bet. He taught me how to scout, how to handicap, how to bet.

Cooney had figured out, early on, that in a completely unregulated system, which Street Racing was at that time, a man with knowledge had an extreme advantage. He was the guy who waited at the finish line with a stopwatch hidden in his hand which was buried in a pocket. Until he taught me, I was one of the mob at the starting line, which was always more exciting.

Drag racing, at a strip or on the street, is simple. Two cars line up side by side and race, straight ahead for a measured quarter-mile. At the dragstrip, each car is measured and delivered time-slips in 1/100th second increments. On the street, all you got was a blinking flashlight for the winning lane.

Cooney measured and codified and when, by his chart, he had a thirteen-second Chevy up against a fourteen-second Ford, he would get down a bet. Or I would, once Cooney got too widely known. He taught me handicapping. He taught me never to bet on a good car with a bad driver. Most of all he taught me restraint, an unusual choice for a nineteen-year-old. He taught me to wait for the odds to come to me.

A Brief Conversation With Lou

Eric: I want to talk about writing and street racing.

Lou (uninterrupted): The thing was, you could actually make a living on the street if you were smart. I had a 14 second car, a 55 Chevy with a built 283 and it would run high fourteens about 95, 96 miles an hour for a quarter mile drag, which was respectable back in the day. But, it didn't look that great and it was considered a sleeper because you couldn't look at it aside from the cheater slicks, you couldn't really tell, you know, what the car was built for. So I got a lot of races against people who sort of underrated it. But the main thing was betting.

The other thing I learned in that scene is that the guys who were the real heroes basically couldn't tell their own stories. The whole point about writing is it's the kids on the fringe. It's the kids who are the observers who really get the story — who will get the story right. Because you're not really part of the scene. You're just one of the squirrels who is seeing what's going down. And so you have to use your imagination quite a lot more.

You can fill in the gaps because you know there are gaps because you know you don't know, the inside story, but, uh, uh, but that was the first time I realized that, you know, being an observer, being an outsider was actually kind of an advantage when it came time to write.

Eric: You talked in classes about the notion of expertise and the importance of, when you’re entering a fictional world, really knowing what you’re talking about because people can tell when a writer is bullshitting. I’ve found that that phenomenon is also true out in the world: you can only fake it for so long about something.

Was that an experience you had in street racing? Where phonies were easy to sniff out?

Lou: You had to know shit, otherwise you would get screwed. In other words, you would pop the hood on a car and, you know, the guy would be claiming that he was running a 265, at which point you would look at the block pad and see if they had a C-code: that was a 265. If it was a 283, it had a different number. If it had a double hump on the head casting you were looking at a 327 with fuelie heads. That was the kind of stuff you had to know, because you're talking about a difference in horsepower. It's only 20 cubic inches, but you're talking about a difference in horsepower of about 40 horses. In other words, you had to have a certain level of expertise to compete.

Eric: Do you consider street racing a sport or something else?

Lou: It's not a sport, it's a way of life. It’s an outlaw sport. Do you know Barnaby Conrad? He was a total dick. He was a toreador, a huge Hemingway follower. And he had this quote that was often attributed to Hemingway, which is he said the only true sports were mountain climbing, boxing, and auto racing, because it’s possible to die participating in them, which is total bullshit. He said everything else is a game. So you could say street racing is a sport in that sense, because you could die.

I probably saw somebody die. Roll over at ninety and go up in flames. I came pretty close myself. This is the shit you do when you're 18, 19, you know? It's just amazing that so many of us survived. Because the cars themselves, the horsepower was impressive, but breaking and handling on those cars was terrible. At one point I talked in that essay about trying to race on Forest Lawn Drive. That was suicidal. It was completely stupid.

Eric: Fitting place to die I guess.

(Editor’s note: Forest Lawn Drive is named for the massive cemetery that sits on the hillside above it.)

Lou: With all the dead looking down on you.

Thank you for reading Sports Stories. Buy Shaky Town, support independent writers and publishers. Don’t drive too fast. We’ll see you next week.