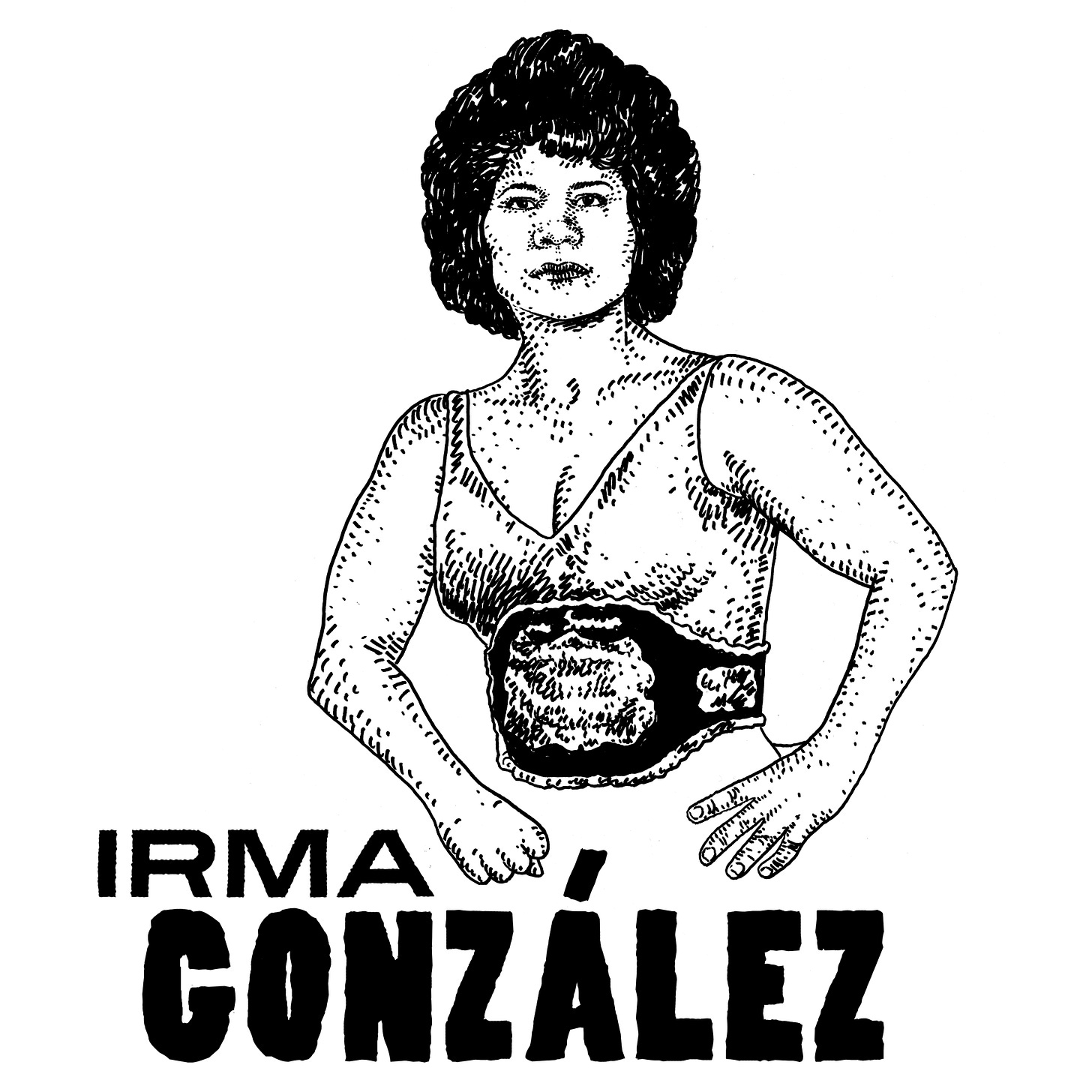

Welcome to Sports Stories, a newsletter written by Eric Nusbaum, and illustrated by Adam Villacin. Every week, we’ll be learning about sports, history, and sports history. We hope you enjoy Sports Stories — and that if you do, you share it with your friends, families, and any lucha libre promoters you might know.

If you are at all familiar with lucha libre, Mexico’s pro wrestling tradition, then you have likely seen the image of El Santo. His sparkling silver mask, the eye holes cut into it the shape of raindrops. The eyes themselves, sincere and anything but violent. He may be shirtless, in his cape. Or dressed in an incongruous suit and tie, muscles bulging through the sleeves.

El Santo was the greatest wrestler in the history of lucha libre. With his wide shoulders, and lumbering, deliberate body language, he was a superhero, conjured from the national subconscious. He transcended the sport. He was Mexico’s biggest movie star, fighting Nazis and mummies and evil space aliens on the silver screen during Mexican cinema’s golden age, and doing it all with his mask on.

He was also, briefly, “married.”

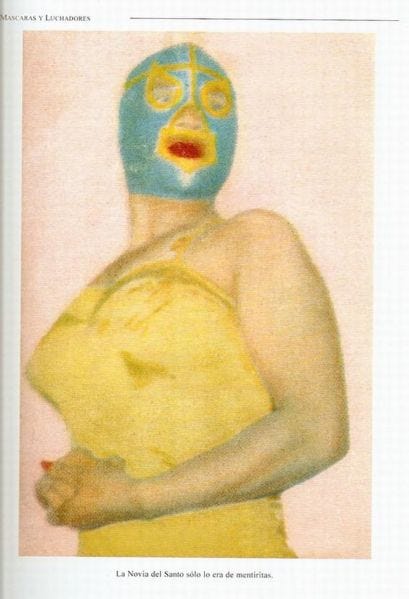

For seven months in 1956, there existed a masked wrestling counterpart to El Santo. Her name was La Novia del Santo, The Bride of The Saint. She appeared suddenly, in a yellow singlet and baby blue mask, in gymnasiums and arenas in small towns all over Mexico. The design of her mask echoed that of El Santo’s. She was talented, and acrobatic. The “romance” never played out in the ring. This was before the attitude era, before television promos and soap opera subplots came to pro wrestling in the USA or Mexico. It was not unusual for a wrestling character to claim a blood link to a more famous star: the sport is full of “Juniors” and “Hijos de” -- sons of. Her name was La Novia del Santo, so she was El Santo’s Novia. It was that simple.

La Novia del Santo was not immensely famous. She was an interesting wrinkle in the legacy of the most important figure in the sport. Until suddenly, she was gone. Over the years, the wrinkle was smoothed out and forgotten.

But La Novia del Santo was more than just a footnote on the career of one of Mexico’s most famous figures. It was also a footnote for the woman behind the mask. She too was a well known wrestler, and she too on her way to becoming a legend of the sport.

Irma González was born in 1937 in Cuernavaca, Morelos, a picturesque town in the shadow of the great volcano Popocatépetl. She grew up everywhere: in small towns and big cities, and on the roads and highways between them. Her father was a professional clown who ran a traveling circus, and from the time she was born Irma was trained to perform alongside her parents and siblings. It was a family act, and Irma learned to be an acrobat, a trapeze artist, a contortionist. She trained and trained. She learned to entertain: to draw the eyes of an audience, to build tension, to hold those eyes.

When Irma was a girl, the family circus was set up in a small town in Zacatecas – it doesn’t really matter which town, but if you really need to know, it was called Lobatos– when everything ended. There was a fire, and when it stopped burning, the circus was gone. No more tents. No more trapeze. No more nothing. Broke and broken, the family moved to Mexico City, into a rough neighborhood where Irma’s maternal grandmother lived.

They were hard times in Mexico City. The family didn’t have its livelihood. There were mouths to feed and there was no way to feed them. Then one of Irma’s new neighbors knocked on the door. She was a wrestler. Women’s pro wrestling was still a relative novelty in the world of lucha libre. This neighbor led a troupe of wrestlers who were heading to the nearby city of Puebla for a tag team match – but one of their members had recently disappeared. Irma was just thirteen, but she had been an athlete; she could leap and she could perform. She could handle a little bit of pain.

The deal was that Irma wouldn’t have to do much. Just stand around. Fill out the match. Fake it. Irma went to Puebla accompanied by her mother. And after that first match, she was hooked. She was a natural. And suddenly, there was money in her life. She started training. She continued to wrestle with her neighbor’s troupe. She went to the arenas and she sat in the stands and watched match after match. She found that the techniques were easy to pick up: it was not so different from the acrobatics she learned in the circus. She could do this.

There was no obvious onramp to “making it” in lucha libre. The infrastructure for women who wanted to be luchadores was practically nonexistent. When Irma first started, there were women’s performances at the Arena Coliseo, in Mexico City’s historic center. They were promoted by Salvadore Lutteroth -- the man considered the father of lucha libre. Irma once recalled that he told her to dial back the acrobatics: she wanted to leap from the ring, and show offer her circus skills. But fans didn’t want to see that from a woman, he said. He was, of course, wrong.

In 1953, the mayor of Mexico City banned women’s lucha libre matches. This meant that wrestlers like Irma had to travel beyond the city limits to perform. Her life became a series of bus rides. She was a teenager, she was usually one of the only women around. And lucha libre was a machismo-driven subculture in a machismo-driven country. It was not easy, and it was not made any easier by the men she was around. They treated her badly. They pranked her. She was less than them. She belonged at home, cooking, cleaning. Anything but wrestling.

When she was still a teenager, Irma fell in love with a man who was not a wrestler. He lived in the United States and before they were engaged to be married, he had just one request: please leave lucha libre behind. Irma had seven months before the wedding. She was in Mexico City, sitting on her hands. He was far away, on the other side of the border. Then something occurred to her: she could become somebody else. She could wear a mask. Anonymity and secrecy were, after all, sacred in lucha libre. If she wasn’t Irma González, then her fiance, as far away as he was, would have no idea that she was wrestling.

“I couldn’t find the right name,” she said years later in an interview with the magazine, Espectacular: El Mundo de Lucha LIbre. “At first, I was thinking La Flor Negra, then there was La Rosa Blanca. I thought also of La Tirana. But none worked for me. One afternoon, while I was flipping through a sports magazine that made it all click. I’d be La Novia del Santo.”

The next day, she sought out El Santo. She asked for his permission to become La Novia del Santo. And in a sign of his respect for the young luchadora, the legend -- he was already a legend by then -- gave it. La Novia del Santo was born. Irma later told interviewers that her identity wasn’t much of a secret: fans could tell it was her, even from under the mask. Her curly hair spilled out from under it, and they knew her body type, they knew the way she moved in the ring. They would cheer her using her real name. But her future husband never knew.

When they were finally married, Irma kept her promise. La Novia del Santo disappeared. (Except for a brief moment, when a man, dressing as a woman, revived the name without Irma’s or El Santo’s permission.) Soon, Irma became pregnant, and soon after that, her husband ran off. A month before she turned twenty, Irma, now once again alone, gave birth to a daughter. She named the girl Irma, after herself. It was 1957, and it seemed like Irma González had already led a full life. It seemed like her career was over. But she was not done yet.

Irma’s husband may have run off, but lucha libre was still there. Now a single mother, Irma became the greatest luchadora in Mexico. She was part of a class of wrestlers who paved the way for more women in the sport, even as her male counterparts filled her suitcases with rocks, and tormented her and fellow luchadoras. She fought her great rival, Chabela Romero, in cities across Mexico, then in countries around the world. She fought in Houston and in Berlin and in Tokyo. Lucha libre took her to Indonesia. The travel was her favorite thing about wrestling, and it was also her least favorite.

Irma had a compact body, a tumber’s body with a low center of gravity. She was indestructible, flying through the air, pinballing off the ropes. She bounced, it seemed, everywhere she went. Even when she was supposed to stay down, it was as if her body never wanted to do, her body couldn't abide the idea of stillness.

One of the women who Irma González paved the way for was her daughter Irma Aguilar. Around the time that the younger Irma turned twenty, she too became a professional luchadora. She had spent her childhood waiting for her mom to come back from her travels, only to watch her turn around and leave again. The younger Irma trained in lucha libre because she wanted to turn and leave too. She wanted to be with her mother, and like her mother. They became tag team partners, and they wrestled together for 25 years. The promoters wanted them both: mother and daughter. Las Irmas.

Irma González’s career spanned the century. It spanned her life. In the 1980s, when women’s wrestling was reinstated in Mexico City, she was there, right where she had been three decades earlier: just as fierce as always.

Outside the ring, Irma González was a strong and calm person. She still is. She has an air of self-sufficiency about her. She tends her flowers. She writes and sings feminist ranchera ballads. Her voice is thick and plaintive. She is 82 years old, and she still teaches lucha libre in a gym in Mexico City. She still lifts weights. At a glance, she looks remarkably similar to the way she does in the grainy footage of her fighting at her peak. A few years ago, she was the subject of a short documentary, simply titled Irma. The film is mostly silent, but it’s a beautiful, intimate portrait of a long, meaningful life.

Related Reading

Lucha libre is one of my favorite things to watch, to write about, to learn about. For the couple years I lived in Mexico City, I couldn’t get enough of it. There’s something about the way that reality and mythology blur together, and there’s something about the folkloric imagery of the sport that just continues to draw me in. The story of Irma González is incredible, an entire Greek epic in a single life, and there are many more like her that comprise the fabric of this sport.

My education in lucha libre came mostly from watching cards in the Arena México and drinking Victorias. Then I started reading, and I discovered that there is a lot of old lucha libre on YouTube, enough to sustain an unhealthy amount of time wasting. I’m not sure where I first came across Irma González, but I know that I first came across the story of Irma and La Novia del Santo in an amazing photo book called Espectacular de Lucha Libre by the legendary photographer Lourdes Grobet. The book features intimate portraits of luchadores, interviews, and assembled history. If you’re at all interested in lucha libre and its history in Mexico, or just want to flip through some amazing pictures, I can’t recommend this book highly enough. (The text is in both Spanish and English.)

Irma has also been generous with her time. If you google her, you can find a bunch of amateur YouTube interviews she’s conducted. She tells the same stories in most of them, but she’ll add a detail here and there as she sees fit. She’s always a good sport.

If you’re interested specifically in women’s lucha, there was an independent documentary in production called La Femenil. You can check out their website, which has features on different luchadoras, including Irma and Irma, here.

Also, just because, here are a couple lucha libre stories I reported from Mexico:

“The Unbelievable Life of Fray Tormenta.”

This was a story for VICE on a drug addict, turned priest, turned lucha libre superstar. Fray Tormenta was the inspiration for the movie Nacho Libre.

“Beso de los Exoticos”

This was my first feature for ESPN the Magazine, many years ago. Looking back now, there are some things I would do differently. It’s an exploration of exoticos: wrestlers who challenge Mexico’s gender stereotypes in the ring. I’m especially fond of the story of Ms. Gaviota, a trans luchadora who works cutting hair in a street-side stall in the historic center when she’s not in character.

The Anatomy of a Lucha

The video above is a clipped together highlight package from a classic lucha libre match between Irma González and her daughter Irma Aguilar in one corner, and Lola González and Zuleyma in the other Watch it. Enjoy it.

This little highlight also happens to contain all the basic elements of a “classic” lucha libre match. I find that it’s helpful when watching to think of lucha libre as a genre of theater performance, with its own conventions. Matches tend to follow a similar script. The beauty is in the creative execution of that script, and in the moments when expectations are subverted.

In American pro wrestling, there are good guys and bad -- faces and heels. In lucha libre, those roles are much more strictly defined. There are técnicos and rudos. The classifications are pretty black and white, and the expectations for how these kinds of wrestlers perform are known to everybody watching.

Another key difference between lucha libre and American pro wrestling is that matches don’t end with a single pin. It’s usually two falls out of three. This means that the tension can build up in a sort of scripted way. Matches almost never finish after just two rounds. And the action amplifies from round to round.

Watch the highlight above: a match that begins with some simple holds, and light contact builds up with each fall into a chaotic, acrobatic brawl. Each round is more exciting, more athletic, more violent than the previous one.

You can also see the técnicos and rudos fully embody their roles. The Irmas are the técnicos here. They wrestle honorably, following the rules, even when it would serve them to cheat a little bit. Lola González and Zuleyma, on the other hand, are rudos. They lie, cheat, and steal.

You’ll see in the third and final round, how Lola grabs Irma Aguilar outside ring, which is obviously cheating. You’ll also see how this backfires, as Irma González saves her daughter, and Zuleyma flies through the ropes into her tag-team partner. This is lucha libre at its purest: stunning athletic performance, ridiculous slapstick routine, and morality play all in one.

This has been Vol. 3 of Sports Stories by Eric Nusbaum (words) and Adam Villacin (art). If you have any questions, comments, or concerns, please reply to this email or contact enusbaum@gmail.com. We’d love to hear from you.

Sports Stories is 100 percent free. If you enjoyed this week’s newsletter, and want to show your appreciation, the best way to do that would be to share it on social media, or forward it to someone you think might enjoy it too.