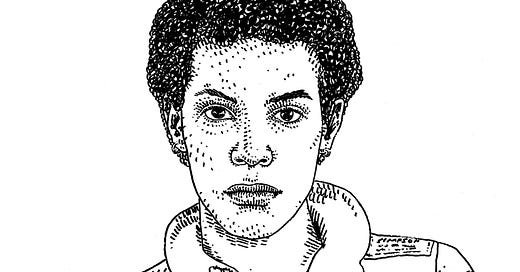

Lady Glass

The first Black woman to become a pro race car driver was a brilliant, complex human being.

Welcome to Sports Stories, a publication at the intersection of sports and history. Sports Stories is written by Eric Nusbaum, illustrated by Adam Villacin, and delivered to your inbox every Tuesday.

If you’re not already a subscriber, please sign up here — we have both free and paid options. Paid subscribers are entitled to our eternal gratitude as well as cool swag including postcards featuring original art by Adam.

When I was writing a historical book a few years back, I had a crisis of faith. The issue wasn’t faith in myself, or faith in the subject matter. It was a matter of questioning the very form, the very practice I was engaged in. My essential concern was that it was impossible to really do a decent job writing about a person who had died and was therefore unknowable on a certain level. Of course, everybody is unknowable on a certain level.

In fiction, you can try to Hemingway your way out of these quandaries. You can tell yourself that you are leaving the inner lives of the characters off the page as a stylistic choice. The rest of your prose will tell that story. The reader will pick the important stuff up via inference and symbolism and clever dialogue.

Well that’s almost impossible to pull of in practice unless you actually are Hemingway or Raymond Carver or something. And it’s absolutely impossible to pull off in nonfiction. There are tricks you can play to keep a story moving, but in general with nonfiction, you have to be clear to readers about what you do and don’t know: that’s the deal. That’s how you earn their trust.

Early on in the book writing process, I had this feeling about Abrana Aréchiga, the woman at the heart of my story. I knew many of the facts but felt this tinge. I knew I would always wish I had more. There’s no real solution here. You just write and write and write until you figure out another way to tell the story, to get as close as you can to what you had hoped for.

I got that feeling again this week reading about Cheryl Linn Glass, a race car driver who lived a remarkable and short life. There’s so much I wish I could know about Cheryl Glass. The beginning of the story is well-documented and surreal and triumphant. The end is surprising and sad. A good place to start with Cheryl’s story is a profile written about her in Ebony in 1980:

“If you have started your own successful business, had a modeling career, been listed in a Who’s Who volume, had a book written about you, amassed hundreds of trophies for driving race cars, and are a smooth disco dancer, it has been quite a life right?”

But for Cheryl Glass it’s only the beginning. After all, she has just turned 18.”

The word I keep coming back to is polymath. Cheryl was a one of those people who had an aptitude for everything, and the curiosity to match. She was born in California and grew up in the Seattle area. Her parents Marvin and Shirley were a telecom executive and a Boeing engineer. As an elementary school student, Cheryl started a ceramics company and quickly began selling her dolls in department stores for hundreds of dollars.

When she was nine, she read an article about kids racing cars in the suburbs. She wanted to try racing, she told her parents. She used her ceramics income to buy a quarter-midget sprint car. Then she simply started winning races. She was usually the only girl and the only Black person at the track.

“I had a rough time when I started,” she told Ebony. “It was more because of color than than being a girl. I just enjoy driving. And I don’t want anyone to stand in my way, especially if I know I can do it.”

From interviews, you get the sense that Cheryl Glass wanted everything and had every reason to expect that she would get it. She graduated to bigger, faster sprint cars. Even as she worked as a model and went to school (she enrolled at Seattle University to study engineering), she told people she wanted to be the first Black woman to race in the Indy 500. To those who knew her and those who saw her race, it was not a ridiculous notion—even coming from a family with no connections in cars in a part of the country that wasn’t exactly a racing hotspot. She became known as The Lady and Lady Glass.

Marshall Pruett of Road & Track wrote a detailed feature on Cheryl’s racing career a few years back and spoke to many of her colleagues and competitors, including Al Unser Jr, who raced against her at a sprint track in Arizona in 1980.

“I didn’t know her that well, but she was a good driver,” Unser said. “She was an abnormality at that time. A female driving sprint cars wasn’t considered normal then. Shoot, it still isn’t something you see happening a lot today.

“She didn’t win, but she was competitive."

Cheryl was in a serious crash in that Arizona race, her car flying off the track at 120mph and flipping repeatedly along the fence before finally settling down. She was badly hurt, but not at all deterred. She rehabbed, then spent the next few years bouncing around different racing circuits, trying to make her Indy 500 dream come true. But she came up against some harsh realities: racing at the highest level required infrastructure and resources that she didn’t necessarily have; it required patience and experience as well.

Glass had skill and confidence, but she didn’t have the guidance of a knowledgable team or the institutional support that could allow her to take her time, and slowly build her skillset. She didn’t get the benefit of the doubt that white men might. Her career choices seemed geared not toward becoming the best driver possible, but simply toward qualifying for the Indy 500. This is one of those places where I wish I could know more about her. Why the singleminded focus on Indy? Was this what kept her going amidst the isolation and pressure of being the only Black woman working as a professional racecar driver for the entirety of her career?

Cheryl’s obsession with the Indy 500 meant she sometimes skipped steps and left herself exposed, racing in cars and on tracks where she wasn’t experienced. Throughout the 1980s and early 90s, she raced all over the place. She was popular. She was by any definition a successful driver. But it never added up to what she wanted to.

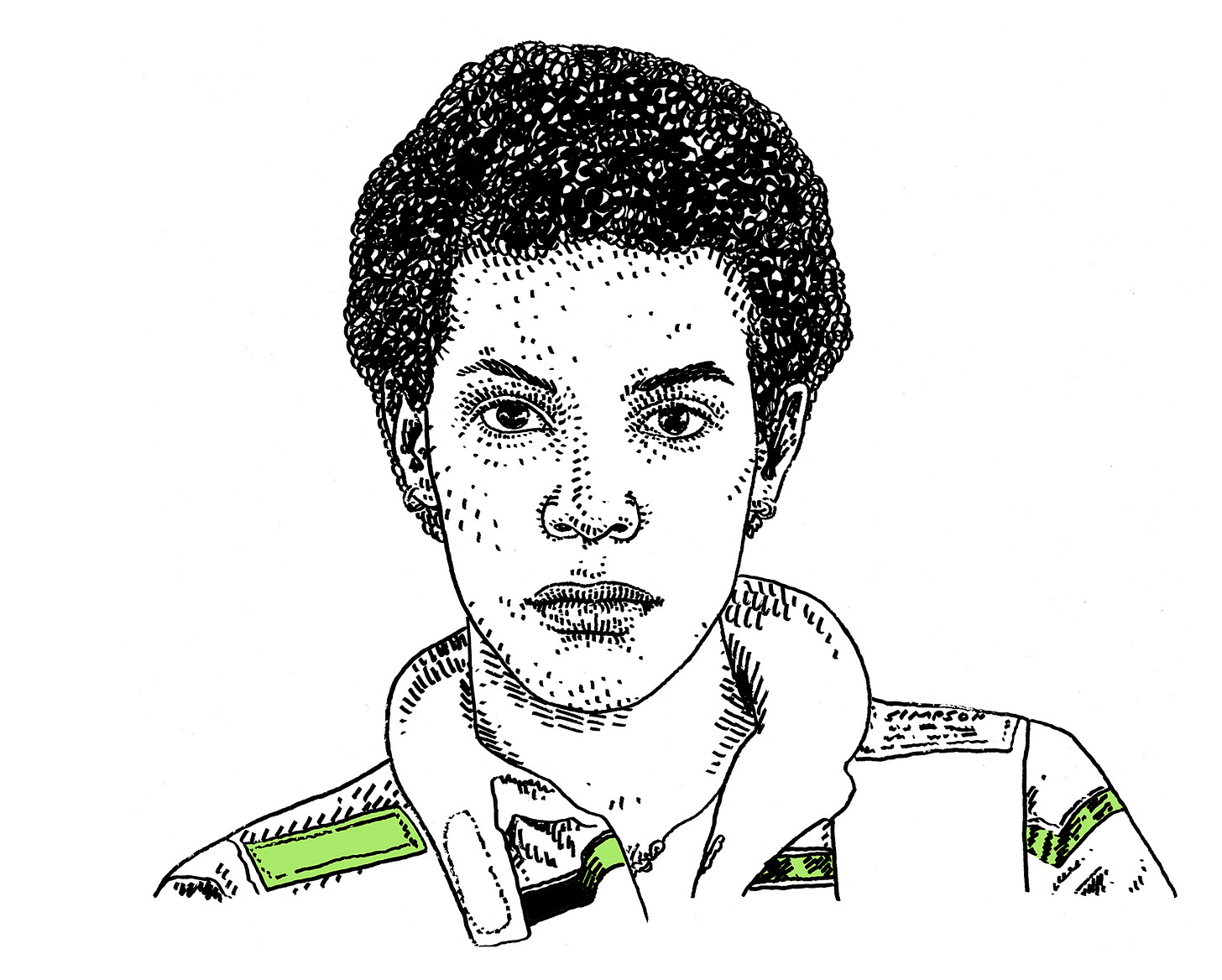

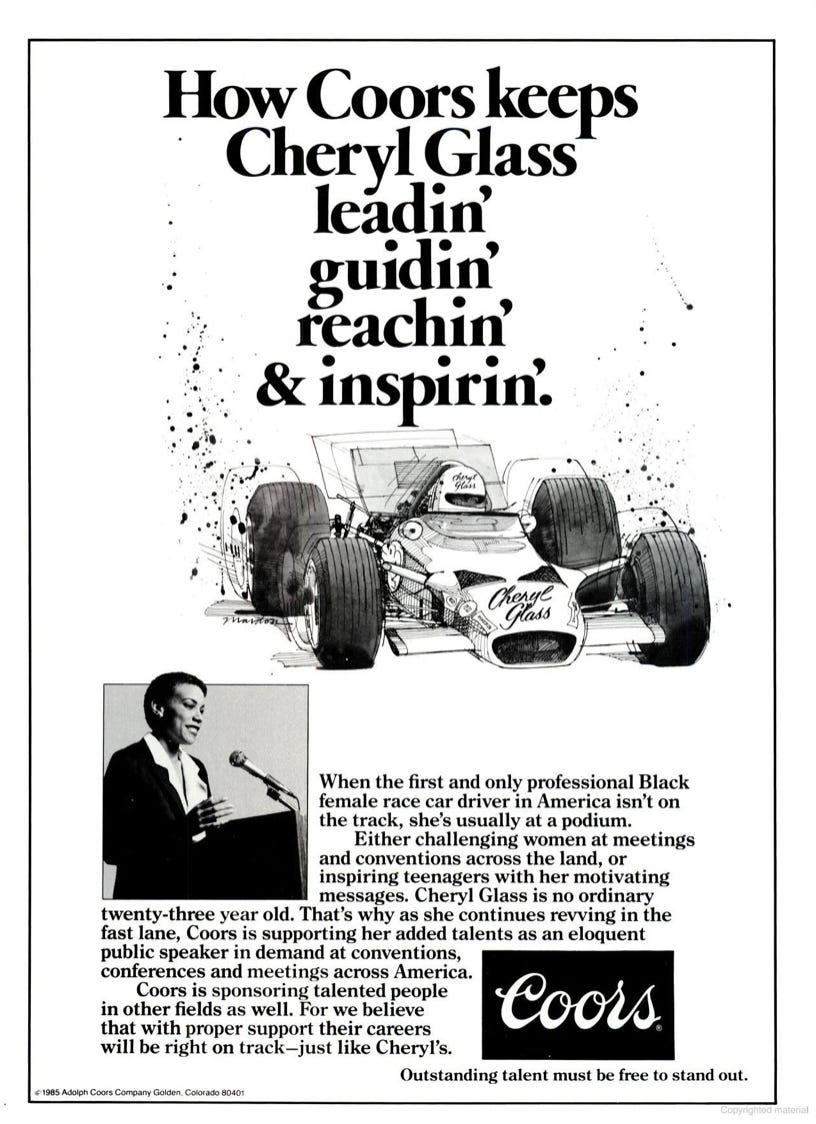

Meanwhile, she had other stuff going on. She worked as a motivational speaker and as spokesperson for Coors. She had a fashion boutique where she designed custom wedding dresses and gowns. She was honored alongside Coretta Scott King at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 1991, Willy T. Ribbs became the first Black man to race in the Indy 500. He spoke to Pruett of Road & Track about Glass:

“There’s more chances of a black woman being an astronaut than being in a race car. I knew who she was before I met her, knew she’d run sprint cars, and knew there’d been none like her before and there’s been none since. A black woman will be president of the United Stated before another Cheryl Glass comes along.”

1991 was also the year that Cheryl Glass’s life changed. First she decided to take a break from auto racing, exhausted by the years of racist and sexist comments she was constantly hearing at tracks. Then she was the victim of a traumatic crime.

That August, three men broke into her home as she slept. Two of the men raped her. The third drew a swastika and the German words for “white power” on her wall with lipstick from Cheryl’s own purse. They burglarized the home as well. Local police refused to pursue the rape, citing insuffiicient evidence. They also publicly speculated that the swastika and hate text may have just been scrawled onto the wall to distract from the burglary.

Cheryl told the Seattle Times that normally she would have had a burglar alarm activated—she had installed one after a previous burglary attempt and “several blown-up mailboxes.” But on this particular night it had been deactivated because of construction going on at the house. Nobody was ever charged.

In the ensuing years, Cheryl had repeated problems with her neighbors and with local police over a variety of property disputes. She alleged that police beat her and improperly arrested her. She brought a lawsuit demanding the resignation of the King County sheriff and other officers. The suit never went anywhere. But it led to what appears to have been the final act of her career: as a fighter for social justice and against police brutality.

After the home invasion and the incidents with the police and her neighbors, Cheryl disappeared from the world of auto racing and mainstream gigs like working for Coors. Instead, according to a letter written by a friend of hers named Reid Swick to the Seattle Times, she became a committed activist:

In the later part of her life, Cheryl sacrificed a lot for her ideals - including her racing career and national celebrity. She came to see these things as less important than her fight against injustice and oppression. In her political development, she fought first for herself, later for the people of the whole world.

When she insisted on her newfound radicalism, she saw many of her former professional contacts and "friends" turn away from her. She came to understand that her former position as successful "role model" had been partly dependent on her continuing cooperation with and promotion of an unjust system.

In 1997, Cheryl Glass fell from the Aurora Bridge in Seattle to her death. The newspapers reported that she died by suicide. But her family never believed that this was the case. There was no note. It made no sense that she would have jumped. The Seattle Times obituary referred to the final years of Cheryl's life as mysterious and tragic. There’s only so much we can know. But we also know that not everybody saw it this way.

Cheryl’s friend Swick wrote:

This is what I will remember about Cheryl - her tenacity, courage, conviction, honesty, warmth and sacrifice; her fearless determination to seek after the truth, no matter what the personal cost.

I think this is far more significant than her professional accomplishments, even as great as they were. And these are the qualities she showed the most in the later "mysterious, tragic" years of her life, when her achievements did not bring media recognition and fame.

Cheryl's whole life should be celebrated. All of us dearly miss her.

Related Reading

Cheryl’s family maintains a detailed website with information on her life and career. The fature from Road & Trackis a truly excellent overview of her racing career; the feature in Ebonyis a great snapshot of Cheryl at the start of her career. Details of the crime and Cheryl’s ensuing battles with law enforcement were published in the Seattle Times and Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Some of that coverage is freely available online, but other stuff—including Reid Swick’s moving letter—are buried a little more deeply in archives.

Another thing I noticed when researching Cheryl was that she regularly appeared in print ads for Coors. I thought I’d share a couple of the ads below:

Thanks for reding Sports Stories. We’ll see you next week.