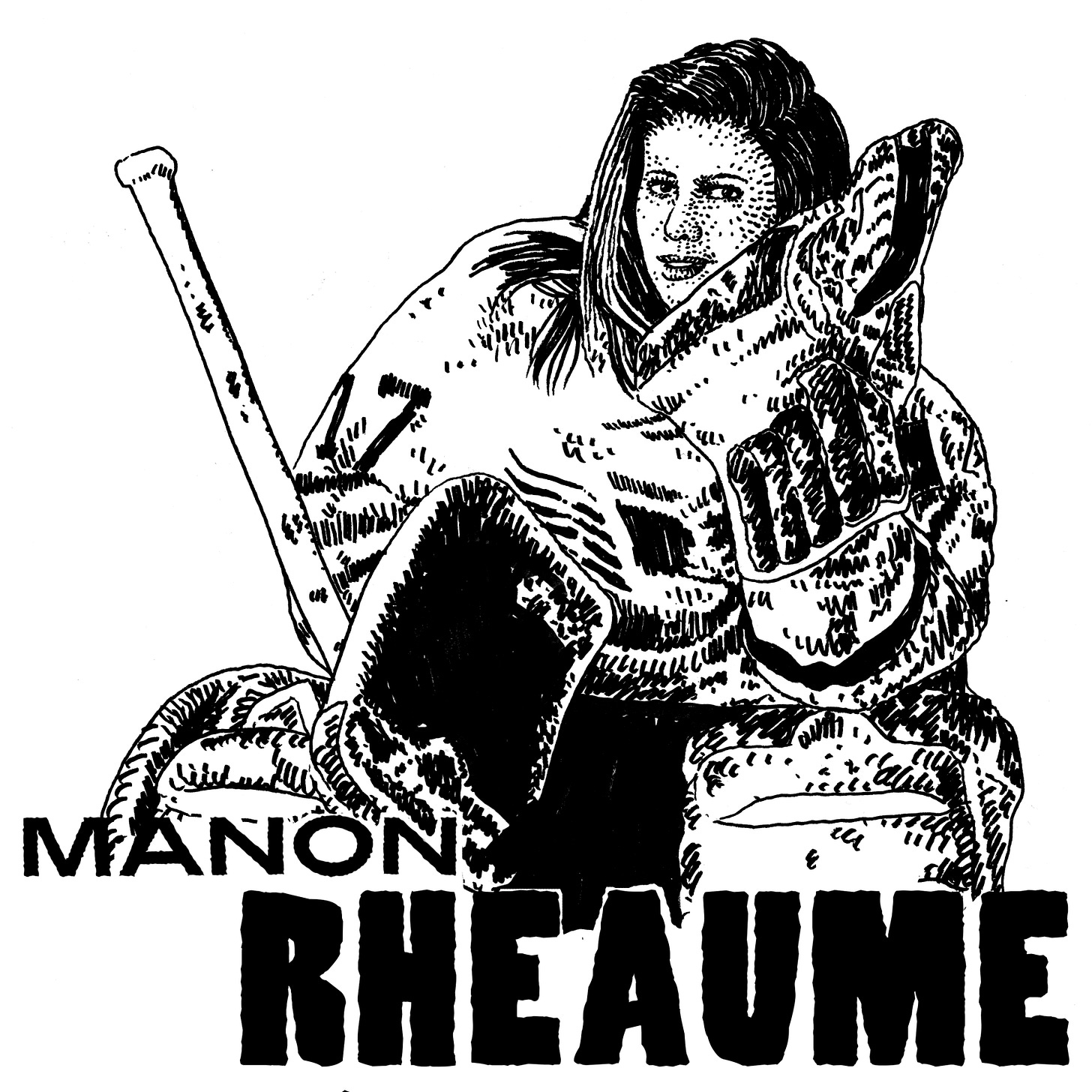

Manon Rhéaume: Lightning Strikes

The story of the only woman to suit up in the NHL is one of athletic majesty, grace under pressure, old time hockey hucksterism, and of course, sexism.

When I was a kid, I collected sports cards. Mostly this habit was about baseball. But I also loved basketball cards (especially Skybox). I loved football cards. And I definitely loved hockey cards. There was something about the texture. Something about the tactile experience. The cards were just little pieces of paper that you could carry around in binders, but they contained everything that was happening everywhere. They were small windows through which to gaze at a large universe that I did not fully comprehend or otherwise have access to. For example, I liked how the little biographies on some old O-Pee-Chee hockey cards were in English *and* in French. That was obviously significant. That was obviously a key to some great mystery.

One of the hockey players who entered my consciousness through trading cards was a goaltender for the Tampa Bay Lightning. Her name was Manon Rhéaume. I was six when she joined the Lightning for training camp in 1992. I remember noticing that she was a woman. It would have been hard not to. And I remember being aware of the fact that there weren’t other women on men’s sports teams, or other women with cards like hers. But to be honest, the fact that Manon Rhéaume entered my consciousness through a hockey card made it so that there was never anything particularly novel about her to me. There was a goalie on the Lightning who was a girl. That was a fact I carried through the sports fandom of my youth. It was on the cards. It just was. But obviously looking back on it, the arrival of Manon Rhéaume in NHL training camp in 1992 didn’t just happen. It wasn’t just was. It turns out, Rhéaume’s is a classic sports story:™ one of athletic majesty, perseverance, and grace under pressure. It’s also a classic tale of old time hockey hucksterism. And, of course, it’s a story about sexism.

Manon Rhéaume was born to a hockey family in Quebec. Her father coached. Her brothers played. (One brother, Pascal, had a solid NHL career.) They had a rink in their backyard. When she was five, her dad needed a goalie for his youth team. Manon said she wanted to play. So she did. And she played well. Then she kept playing, and kept playing. There was never any sense that this would lead anywhere. It was just that Manon Rhéaume loved hockey. She loved playing goalie. And she was damned good at it.

She was good enough to get a shot playing in major juniors, the first woman to do so. It was just one appearance, with Trois-Rivières Draveurs of the QMJHL. She took a slapshot to the mask, and bled so much they had to take her off the ice for stitches. But she performed well, and she impressed an NHL scout in attendance. This scout sent a video of Rhéaume to his boss, Phil Esposito, a retired Hall of Fame player, who was then the general manager of the Tampa Bay Lightning.

Esposito has told the story many times. But he rarely tells it the same way twice. The gist is that he was impressed by the goalie on video. The kid was undersized, but moved well. Then, only after Esposito decided he wanted to sign this young goaltender, did he find out that she was a woman. When he did find out, signing Rhéaume became more than a hockey move: it became an imperative.

It’s worth stepping back to consider the forces at play. In 1992, the Tampa Bay Lightning were not just any old hockey team. They were an expansion franchise, and an experiment for a league that was about to begin to attempt to conquer the sunbelt. There was a lot of skepticism over whether hockey would work in a place like Tampa -- or in the years to come, in places like Phoenix, Miami, Raleigh, and Atlanta. Esposito had helped found the team. He was not only the president and general manager of a new franchise, but the person guiding the NHL’s foray into this new territory.

Last week we learned about the Harlem Globetrotters and Abe Saperstein. Well, Esposito had some Saperstein to him. He saw, in Rhéaume, an opportunity to draw publicity to his new club from the national media -- and an opportunity to draw the attention of fans in Tampa/St. Pete. This was a franchise that would play its inaugural season in the exhibition hall of fairground, and the following handful of seasons in the domed monstrosity that is now known as Tropicana Field, home to baseball’s Rays. The team’s ownership, led by a group of distant investors in Japan, did not care about hockey. The team was constantly broke. Esposito may not have known exactly what awaited his Lightning. But he certainly saw that hockey had a rough rink to Zamboni if it was going to catch on in Florida.

Esposito was up front about the fact that signing Rhéaume was a publicity stunt. He told the papers exactly as much even as he praised her talent. And as a publicity stunt, it was a huge success. Media from across the country came to Tampa to cover her. She was the talk of the league, and the talk of many people who otherwise could not have cared less about hockey. The presence of Rhéaume in Lightning camp was called sexist by a lot of hockey writers. (These were male hockey writers, essentially the only kind that existed in 1992.) Sports Illustrated scornfully compared the signing to the time in 1951 when the St. Louis Browns signed the 3’7” Eddie Gaedel to appear in a game.

But this was a reductive way of looking at things. Yes, she was a total longshot to make the team, but Rhéaume could play. Esposito also knew that. And the Lightning organization gave her a real chance to play, despite the fact that their head coach, Terry Crisp, wanted seemingly nothing to do with her. She participated in training camp just like the male goalies, and performed well. She was instantly bombarded with media requests, but handled them gracefully. She was twenty years old, and she was suddenly an international celebrity. She told people that this was an opportunity to get better as a goalie, to play against the best in the world. This was something that -- as an athlete -- she could not pass up, regardless of gender. Years later, she explained to a much more nuanced Sports Illustrated writer that the entire world had always been telling her no simply because she was a girl. “If this time, someone says yes to me because I’m a girl, I’m going to take that opportunity.”

When she finally appeared in a game, on September 23, 1992, it was a monumental event. Rhéaume understood the stakes, too. It may not have mattered in the standings if she played poorly, because this was the preseason. But it mattered. She felt the weight of being first. Rhéaume played one period, and she played relatively well. She stopped 7 of 9 shots, and made a couple of really nice saves, including one on an early blast from Brendan Shanahan. Then it was over. She took an assignment to the minors, and a few months later, she gave up pro men’s hockey.

The truth is, Rhéaume’s mere presence with the Lightning in 1992 changed the way we thought about sports. It certainly changed the way I thought about sports, without my even realizing it. The tryout, and the exhibition appearance, put her on the hockey card. And as an athlete, that’s where she deserved to be: regardless of whether or not she was on the Tampa Bay Lightning.

One thing nobody mentioned during her NHL career was that Rhéaume had led Canada to a gold medal at the World Championships earlier in 1992. She would do the same in 1994. Then, in 1998, Rhéaume would play for Canada in the first ever women’s hockey tournament at the Winter Olympics. Canada took silver. These achievements were worth celebrating on their own. It would be unreasonable to claim that Rhéaume’s brief, glorious career with the Lightning led directly to an increase in the popularity of women’s hockey. But it would also be silly to think that if it changed my conception of what was possible, as a little kid in Los Angeles -- it did not also do the same for young hockey players across the continent.

Rhéaume retired in 1999, after she became a mom. She worked in youth hockey outreach, and still coaches in the Detroit area. I reached out for an interview for this story, but unfortunately did not hear back.

Where We Were

One of the pleasures of writing about Rhéaume (who is a historical figure, but a relatively recent one) has been the amount of easily attainable material on her life to go through. Reading all the old newspaper clippings, it’s easy to see how much and how little has changed in regard to how we talk about and think about gender in sports (and in the society of which sports are a part). To be honest, reading these old stories has made me appreciate the fact that things are better. Many writers in sports departments in the early nineties apparently weren’t even capable of putting together three coherent sentences about women playing sports.

In 1992, there was no WNBA. There was no NWSL. And there was no NWHL. (The National Women’s Hockey League, fascinatingly, was founded by a former women’s hockey player named Dani Rylan, who grew up in Tampa and called Rhéaume a hero; Rhéaume dropped the puck at the inaugural game in 2015.)

But in 1992, Dani Rylan was still a little kid. The NWHL was a long way away. And Rhéaume was still working hard just to be taken seriously by people like David Letterman. I watched this interview and was horrified for five solid minutes:

Then I watched a television segment from the era featuring another great French Canadian goaltender, Patrick Roy. In addition to having excellent early ‘90s vibes, this one actually seemed to get it:

Related Reading

As always, the place to start with these things is books. Rhéaume wrote an autobiography called Manon: Alone in Front of the Net that was published in 1997. Her career has been written about extensively before and after that book was released. If you look at the archives of surviving newspapers from 1992, you’ll come upon all kinds of contemporaneous reportage. Otherwise, just run “Manon Rhéaume” through your search engine of choice. It’s all there. She has been generous with her time as both an advocate of women in hockey, and as an interview subject for journalists.

Here’s a good short documentary with lots of footage, and interviews with Rhéaume and Esposito:

This has been Vol. 8 of Sports Stories by Eric Nusbaum (words) and Adam Villacin (art). If you have any questions, comments, or concerns, please reply to this email or contact enusbaum@gmail.com. We’d love to hear from you.

Sports Stories is 100 percent free. If you enjoyed this week’s newsletter, and want to show your appreciation, the best way to do that would be to sign up, share it on social media, or forward it to someone you think might enjoy it too.