Nobody Beats the Biz

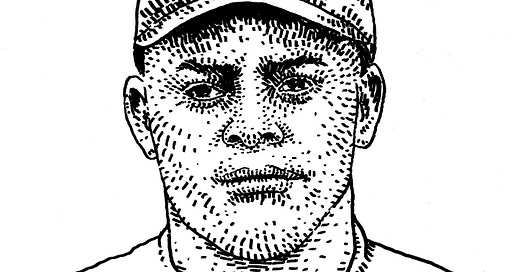

The story of Negro League legend Biz Mackey, one of greatest catchers to ever do it.

Welcome to Sports Stories, an illustrated newsletter at the intersection of sports and history. If you’re not already a subscriber, please consider joining up here.

If you’re a longtime reader, or just enjoy this post, please consider doing us the favor of sharing Sports Stories. You are the reason we do this, and also happen to be our best (and only) marketing system.

This goes without saying, considering the nature of this newsletter, but I love writing about history. I love the way stories weave together and trace back and connect in places that you would never suspect. You can learn a lot about something, and even write about it, only to come back to that topic and find a detail that you had just completely missed.

For example, Biz Mackey.

A couple years ago, I published a book called Stealing Home, the climactic moment of which was the violent eviction of the Arechiga family from their home in the community of Palo Verde by sheriff’s deputies in order to make way for the construction of Dodger Stadium. I set up the scene with a chapter taking place night before the evictions. The Arechigas were sitting at home, waiting for the inevitable. Meanwhile, the newly christened Los Angeles Dodgers were playing an emotional exhibition game at the Memorial Coliseum to honor their former catcher Roy Campanella.

Campanella, arguably the greatest catcher in big league history, had been paralyzed in a car accident shortly before the Dodgers moved to LA from Brooklyn. For the exhibition, the Yankees came out to the west coast to honor their old rival. Sandy Koufax started for the Dodgers and nearly 100,000 people filled the stadium. It was a beautiful scene. At one point, Campanella entered the field accompanied by a few friends. The lights were dimmed and the crowd raised lighters in unison. In his autobiography, Campanella likened the stadium to a giant birthday cake ablaze in his honor.

What I didn’t realize was that one of the people standing there on the field with Campanella was his catching mentor, Biz Mackey, a legend of the sport in his own right. Perhaps the reason I didn’t realize this was because the LA newspapers that covered the Campanella game didn’t mention Mackey. The team didn’t do anything specific to honor his presence. He was just there, supporting his friend.

Biz Mackey was widely considered the greatest defensive catcher to ever suit up in the Negro Leagues. He was also a .300 hitter, beloved manager, and a jovial personality who got the nickname Biz for his propensity to never ever close his mouth. It was Biz as in The Business, which is what he was always giving to everybody around him: whether as a boy in East Texas, a superstar in Philadelphia, or an ambassador for the game on barnstorming tours in Japan. Friends, opposing players, umpires -- Biz talked to everyone.

Biz was born Raleigh Mackey in 1897, to a family of sharecroppers. He came up playing semi-pro ball and hopped around to increasingly talented teams as he entered his prime: the Luling Oilers, the Dallas Black Giants, the Waco Navigators, the San Antonio Black Aces. Then beyond Texas to the Indianapolis ABCs and ultimately the Hilldale Daisies in Philadelphia, where he would remain for a decade and establish himself as a superstar alongside folks like Martin Dihigo, Oscar Charleston, Judy Johnson, and Pop Lloyd.

I am wary of the practice of comparing Negro League players to their white counterparts because I think this does them an inherent disservice. You don’t need to see a player in one specific context, or through one specific lens to appreciate their abilities. If anything, I think the increased centralization of our thinking about baseball and what counts as “major league” has done harm to our ability to appreciate greatness everywhere. (This also goes for MLB recently deciding to grant Negro League stats “official recognition,” a problematic gesture that Clinton Yates wrote about very powerfully last year for The Undefeated.)

Anyway, all that said, his peers compared Mackey favorably to MLB catchers like Bucky Dent and Mickey Cochran. He wasn’t the power hitter Josh Gibson was, but a case can be made that he was the greatest defensive catcher of all time -- in any league. He became famous for all the broken fingers he suffered on his right hand, and for the way he would gun down prospective base stealers without getting out of the crouch. He also played some shortstop. Mackey’s career took him across the United States and Latin America. He also was part of multiple barnstorming tours in Japan.

Last year, we wrote about Matsutaro Shoriki, the Japanese newspaper mogul who brought Babe Ruth to Japan in 1934 as part of a tour of big leaguers and nearly paid for it with his life, when he was attacked by an extremist wielding a samurai sword. Seven years prior, a group of Negro League stars visited Japan, and Mackey was among them. He reportedly hit the first home run at the brand new Meiji Jingu Stadium. During one game, he was struck by a pitch. The offending pitcher bowed in apology, and Mackey gained fans when he bowed back before trotting to first base. Japanese baseball was not exceptionally developed in 1927, and the Negro Leaguers earned the respect of audiences for putting on a show without showing up their opponents. They were greeted by Emperor Hirohito, who presented them with a trophy.

During that trip to Japan, Mackey also fell in love. He met a woman named Lucille in Tokyo. They wrote letters and would see each other on future barnstorming tours, which Mackey always made sure to find a place on. When World War II came around, they lost touch.

Mackey bounced around between teams in the 1930s and ultimately became a player-manager. It was under this capacity that he mentored Campanella. Mackey was still suiting up for the Newark Eagles as late as 1947, the year he turned 50 and the year Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby broke into white baseball. Doby had been playing for Mackey’s Newark Eagles before his contract was sold to Cleveland.

Then something amazing happened. At some point in the years after the war, Biz and Lucille got back in touch. They were ultimately reunited in San Francisco and moved together to Los Angeles, where Mackey had played winter ball. Mackey and Lucille lived a quiet life. He worked as a forklift operator and for a change, he didn’t talk about baseball much. He walked out onto the field that night beside Roy Campanella. He passed away in 1965.

Related Reading

Biz Mackey was elected to the baseball Hall of Fame in 2006, which was only about fifty years too late. But to their credit, Black papers like the Pittsburgh Courier had been touting his greatness for decades. Thankfully, there’s a fair amount of material out there on Mackey. I would start with the SABR bio by Chris Rainey, which is an excellent and detailed survey. If you want even more, check out the book “Biz Mackey, a Giant Behind the Plate” by Rich Westcott. The first chapter is available to read here.

(Necessary parenthetical here: there is no evidence that there is any connection between Biz Mackey the ballplayer and Biz Markey the rapper. Just two cool dudes with similar names. To make it even more confusing, there was also a pretty successful boxer in the early twentieth century named Biz Mackey.)

I also really liked this piece by my former Vice colleague Dexter Thomas for Code Switch on NPR about the history of Black players in Japan.

If you’re into collectibles, an original program from Mackey’s first barnstorming tour featuring a beautiful photo of him with a Japanese player on the cover recently sold for about $3,156.38.

Finally, I really enjoyed this piece by the legendary Japanese baseball historian Kazuo Sayama on how the Negro League barnstorming team spurred the development of baseball in Japan.

Thanks for reading Sports Stories. We’ll see you next week