Welcome to Sports Stories! We write and draw a newsletter at the intersection of sports+history every week. If you’re not already a subscriber, please sign up here—it’s free!

Earlier this month, it snowed in Tacoma where I live. There was so much snow. Beautiful and fluffy and perfect. At one point I found myself standing on the street, staring off at a tree in the distance. Then without even thinking about it, I was chucking snowballs at the tree, one after another.

My kids were playing down the block. But I just locked into this tree trunk. There was something so pure about the moment. The gentle falling snow. The quiet of the city. The way the snowballs packed into my hands, the way they rolled off the fingertips of my glove perfectly with each release. And me, 34 years old but feeling like a child, all alone in it. (Keep in mind, I’m a person who has spent most of his life in Los Angeles. Winter is still a novelty for me.)

I must have hit that trunk dead center a dozen times in a row, perfect strikes, before something snapped me out of it. Maybe it was one of the cargo planes flying low over our street on the way to the base nearby. Maybe it was one of my kids, sledding down the neighbor’s front lawn. Either way, whatever magic I had before was gone. The next snowball I threw sailed past the tree and off a car. The next one missed too. Suddenly, I couldn’t hit shit.

There’s something so precarious about the ability to master and repeat an athletic act. I find that as a sports fan it helps to pause every once in a while and think about precisely what the athletes we watch are doing. Major league pitchers—who reported to Spring Training last week—are expected to throw a baseball at superhuman speeds and hit a tiny box 60 feet, 6 inches away. Also the location changes pitch to pitch. And sometimes the ball has to curve, dip, or give the appearance of slowing down in mid-air.

It’s easy for the miracle that is the simple act of pitching to get lost underneath stats and noise. After all, this is not something many of us try to actually do. And the only people we do see pitching baseballs are the very best in the world at it. So maybe we don’t fully appreciate how much has to go right for the execution of a single major league strikeout.

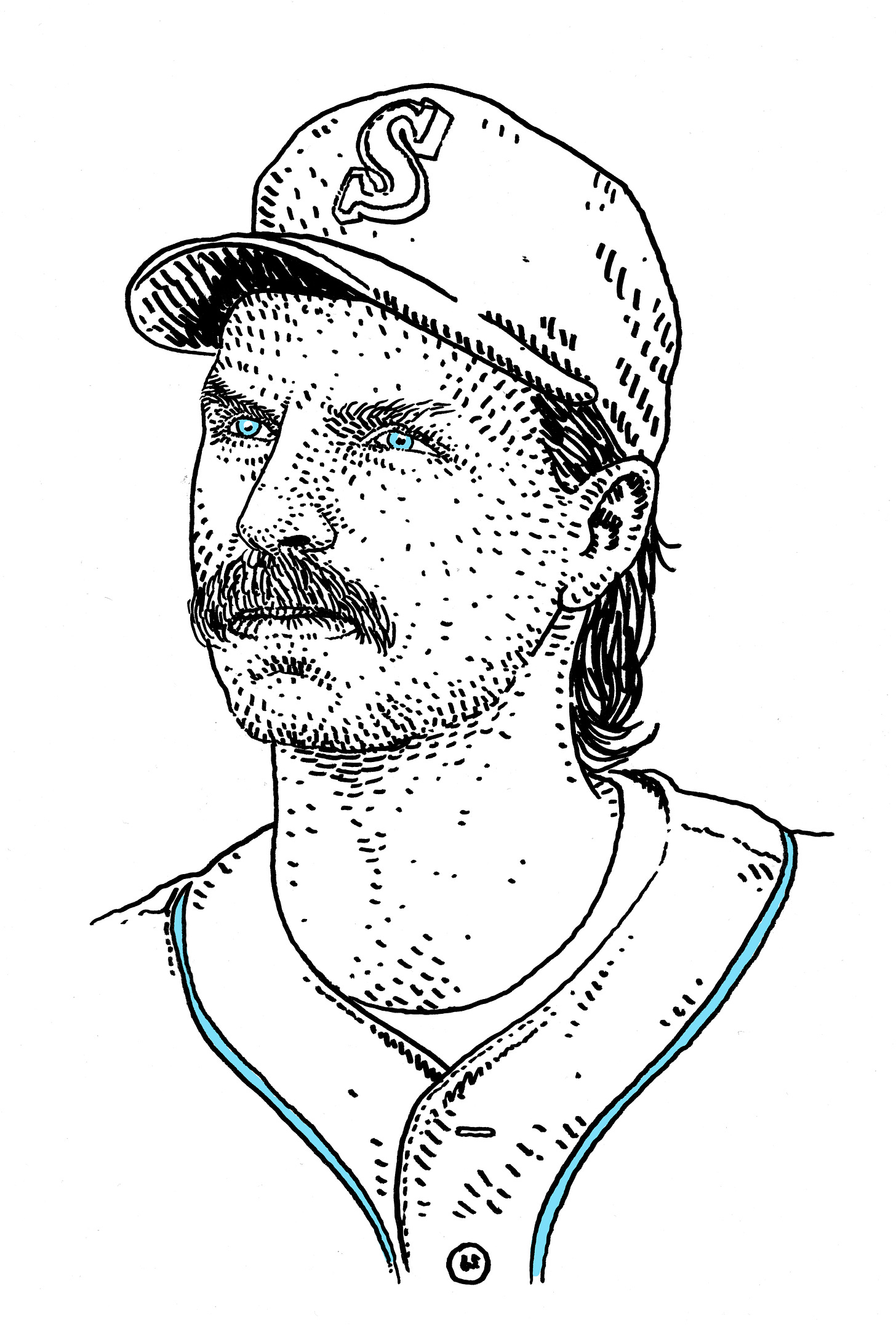

I’ve never interviewed Randy Johnson but I am pretty sure he appreciates how difficult it is to throw a single strike—much less three of them. Johnson is one of the most interesting professional athletes to grace us with his presence. He was a truly terrifying figure on the mound, unlike anything ever seen before or since: Six feet, ten inches tall. Left-handed. Long hair and pockmarked face that somehow made him seem kinder and gentler than he actually was. A dove once flew into the path of a Randy Johnson fastball—and literally exploded. He recorded 4,875 major league strikeouts. The only person with more is Nolan Ryan.

But it didn’t always look like it was going to go this way for Randy Johnson. In fact, it took him a long time to figure it out. He was drafted by the Montreal Expos in 1985 out of USC. That year, his first as a professional, Johnson was objectively terrible. In 27 ⅓ minor league innings, he walked 24 batters. His earned run average was 5.93.

Johnson had so much going for him. It wasn’t just his size either, or the velocity with which he could throw a ball (very fast). There was the violence of his delivery and the way the ball whipped out of his hand like something paranormal. But that didn’t mean anything if he couldn’t throw strikes. Pitching well requires grace and balance and the ability to repeat a very complicated and unnatural series of movements to near perfection. At nearly seven feet tall, there was simply a lot of body for Randy Johnson to try and control.

He sort of succeeded for a while. His numbers improved in the minors, and improved further when he was traded to Seattle in 1989. But it was never great. There was something slightly off about Randy Johnson. Every windup, every pitch was like the equivalent of a town of medieval villagers gathering to build a giant catapult and then launching their very first rock. It was slow and it was potentially dangerous but you never really knew if it was going to work. This could be a good thing—Johnson’s wildness scared the shit out of hitters. But ultimately it was not sustainable as a path to actually getting guys out.

“The hitters feared the man and the stuff, but they did not fear the pitcher,” Johnson’s former minor league manager Felipe Alou said years later.

Then in 1992, something amazing happened. Johnson was 28 years old by that point. He was a veteran, in his third straight year as a slightly above average starter for the Mariners. But he was still plagued by the old inconsistencies. The brilliance and the wildness. He had thrown a no-hitter a couple years prior, but still it always seemed like it was on the verge of falling apart. Some nights it did.

What happened in 1992 was that Johnson and Nolan Ryan struck up a conversation before a Mariners-Rangers game. It turned out that Ryan, by then 45 years old, noticed something about Johnson’s mechanics. When he completed his throwing motion, Johnson landed on his heel, causing him to fall backwards toward third base. Ryan thought this might be impacting the big lefty’s control. Ryan also brought Rangers pitching coach Tom House into the conversation. Together, Ryan and House, convinced Johnson that he ought to try landing on the ball of his foot instead of his heel.

This turned out to be the key that unlocked one of the greatest pitchers in baseball history. Johnson spent a week that offseason working out with Ryan in Texas. Then in 1993, he cut his walk rate almost in half.

It would be easy to write that the rest is history, which I guess it sort of is. Johnson became an iconic, intimidating, hilarious, deeply and beautifully weird baseball legend. But it wasn’t as if he just solved pitching that afternoon with Nolan Ryan. The rest of his career was spent refining and adjusting and working, working, working to maintain that balance. After all, Randy Johnson knew as well as anybody how easily it could all slip out of his left hand, and never return.

There are some corny but worthwhile fortune cookie lessons here. For example: you’ve gotta stay at it. For example: you never know when the moment will come when you’re going to figure it out. For example: sometimes wisdom comes from the place you least expect it—even an ostensible rival. For example: even when you have control, you only have so much of it.

But what I love about the Randy Johnson story is that the newfound ability to throw strikes didn’t totally change the guy. It wasn’t like he went from dour to cheery in nature. It wasn’t like he completely revamped his approach to pitching. You can grow and evolve and still be who you are. Like Nolan Ryan, Randy Johnson pitched into his mid-40s. He won a World Series. Ten All-Star games.

He found control. He held onto it for as long as he needed to.

The Big Unit

If Sports Stories (now into our third calendar year!) is Randy Johnson, then we need you to be our Nolan Ryan. Making this newsletter every week is a practice that Adam and I love—but the opportunity to share it, the fact that folks are out there looking forward to reading and checking out the art, gives us the focus and discipline we need to throw proverbial strikes.

In other words, Sports Stories can’t grow without your help. And it wouldn’t be what it is without your support.

If you are a subscriber who enjoys these newsletters, please consider sharing them with people in your life who you think might enjoy them too. This is the single biggest way we get new readers. Here’s a button for that:

If you are a reader with some extra cash to spare, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Here’s a button for that:

And if you are a reader with an impeccable sense of fashion and style, please consider checking out our new online store. Here’s a button for that:

Related Reading

My favorite read on Randy Johnson’s journey to control is this 2009 feature from the San Jose Mercury News, written by Andrew Baggarly who now covers the Giants or The Athletic and also happens to be a three-time Jeopardy! champion.

I also really appreciated the anonymous blogger who reprinted a conversation between Randy Johnson and Nolan Ryan about pitching mechanics that appeared in a a 1996 Mariners team magazine. It’s truly revealing -- also fascinating to see the humility in Johnson as he speaks to a man he clearly admires:

Five years ago, if I had problems with my delivery, I was done. It was just a matter of when the manager was going to come and get me. But now, for the most part, I know when I’m doing something wrong because I’ve become so consistent in my mechanics. For instance, when I’m falling off toward third base, I know how to correct that now.

Finally, this is a fun story on Randy Johnson figuring himself out from Bleacher Report’s Scott Miller. Word to the wise: don’t drink the Big Unit’s orange juice.

Thank you for reading Sports Stories. We’ll see you next week.