That Time the Milwaukee Bucks Played the Soviet Union

In 1987, the Bucks took on the USSR in the finals of a tournament called the McDonald's Open

Hi. Welcome to Sports Stories, an illustrated newsletter at the intersection of sports and history.

If you’re not already a subscriber, please consider joining up here — we have both free and paid options. If you enjoy Sports Stories, please share it with your friends. Word of mouth is our best (and only) means of publicity.

You can also buy some merch, including shirts, hats, zines, and postcards, at our very cool web store.

You might have heard this week about the Milwaukee Bucks’ long NBA finals drought. You might have read that the games they are currently playing against the Suns are the the Bucks’ biggest since about 1974. And in the context of the NBA, that is true.

But you don’t have to go back quite as far to find the Milwaukee Bucks in a huge basketball game on their home court -- only as far as 1987, when they represented the United States in a brand new international club basketball tournament called the McDonald’s Open.

The McDonald’s Open was a pretty straight forward endeavor. Club teams from around the world competed for bragging rights, $50,000, and (I imagine) a trophy emblazoned with the moon-shaped face of former company mascot Mac Tonight. The ‘87 tournament was extra important because it was the first of its kind, and also because mixed in amongst the club teams was the national men’s team of the Soviet Union.

In retrospect, the fact that they were playing in a tournament sponsored by a globally ambitious fast food company should have been a clue that things were not going great politically for the USSR. Regardless, they found themselves in the tournament’s final round robin group, with the Bucks and an Italian club called Tracer Milano.

The winner of the tournament would be the team that performed best in a mini round robin. Tracer was actually pretty good -- their roster included a washed up Bob McAdoo and a superstar American point guard named Mike D’Antoni. But they weren’t on the same level as the other two clubs. "I just hope we don't embarrass ourselves," D’Antoni said before Milano faced the Bucks. They didn’t embarrass themselves, but they did lose both of their games. This set up the matchup between the USSR and the Bucks as a de facto title game.

As with any sporting event pitting the United States against the Soviet Union, there was lots of interest and there was lots of Cold War talk. But the scene at the Milwaukee Exposition Convention Center and Arena (MECCA) was much stranger and more surreal than you might have seen at, say, an Olympics. Here’s the legendary Jack McCallum in Sports Illustrated:

While the Soviets didn't exactly revel in the attention given them by the promoters and the press, neither did they find it distasteful. Strange, perhaps, but not distasteful. Following their practice one morning, they took center stage at the obligatory feeding frenzy at McDonald's and then visited Kohl's, the department store owned by Bucks owner Herb Kohl. There they were given sweatshirts—red, of course—jean jackets and teddy bears (Gomelsky politely refused his). That night they saw Fatal Attraction at the West Point movie theater.

The Gomelsky who refused the teddy bear was the somber looking Soviet coach, Alexander. Somehow, Bucks coach Del Harris was even more somber. At the start of the broadcast, Harris spoke soberly about wanting to do right by his country and make his family proud. “We’re also representing the NBA, of which we’re certainly a part,” Harris said, helpfully.

Before the game, Gomelsky presented Harris with a little commemorative banner -- a kind act of diplomacy that would not be reciprocated on the court. The tournament came at an interesting time in terms of the two nations’ basketball relationship. NBA teams had recently begun drafting Soviet players with the hopes of holding onto their rights and perhaps one day signing them to contracts. But the prospect still seemed far-fetched.

“Rumor has it that some of these guys are going to play in the NBA,” said Dick Vitale on the broadcast. “I think I have a better chance of growing hair or replacing Bruce Willis as a sex symbol on ABC.”

Vitale, of course, was wrong. Just a couple years later, one of the Soviet team’s stars, Sarunas Marciulionis, would go on to be the first Soviet player to sign with an NBA team. It’s clear watching tape of the game now that the Soviet squad had some NBA caliber players. Marciulionis would have a really nice career, mostly with the Warriors, and get credit for bringing the Euro step to the NBA. Alexander Volkov would play a couple years with Atlanta. And star center Arvydas Sabonis, who was injured for the McDonald’s Open, well, he was Arvydas Sabonis.

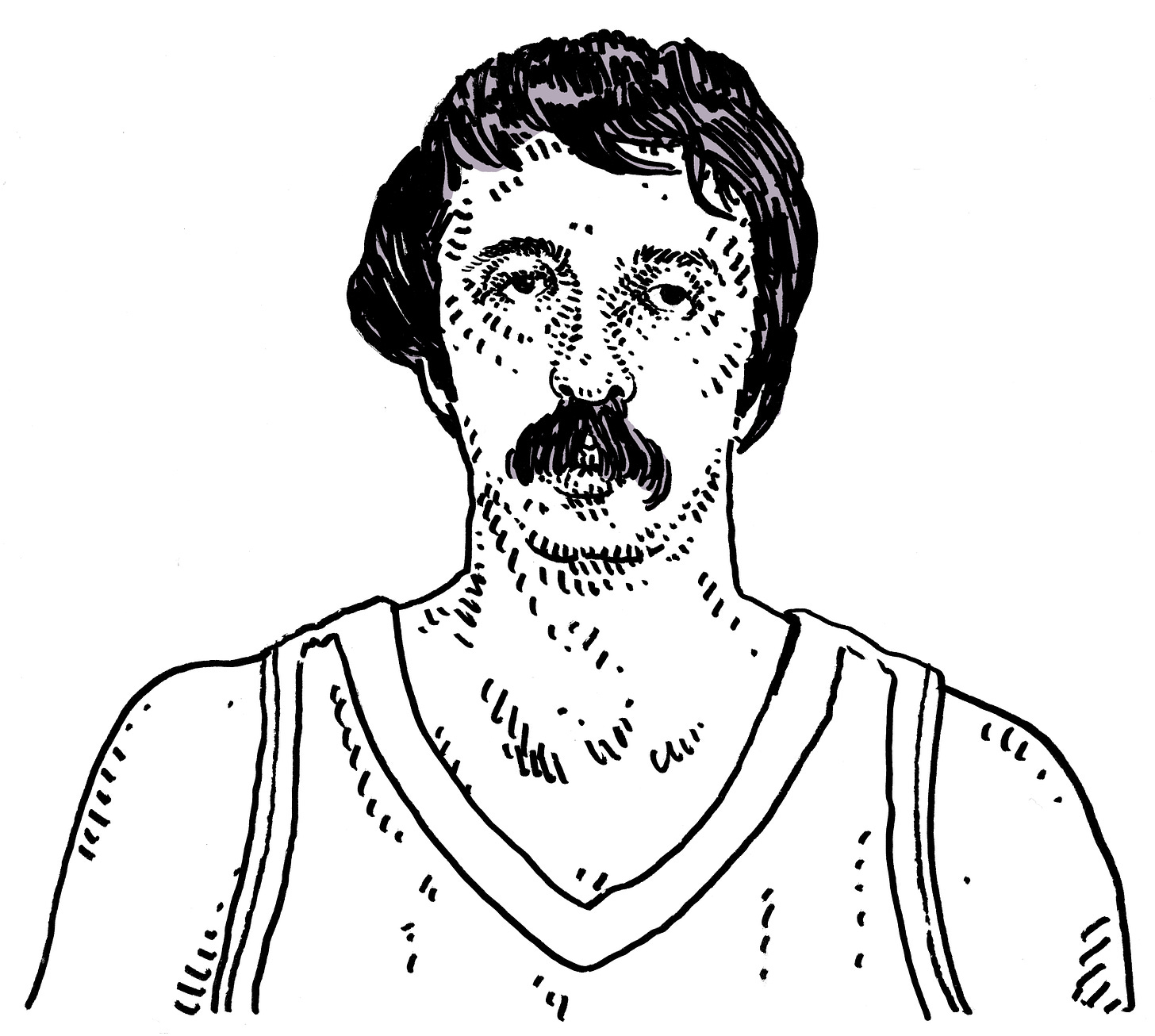

But it’s also clear that the Soviets were overmatched. The injury to Sabonis led to ridiculous center Viktor Pankrashkin getting some extra playing time. Pankrashkin was seven feet tall with no muscle whatsoever, a tummy like Winnie the Pooh, and a drooping Kurt Vonnegut mustache. In Sports Illustrated, McCallum described him as having “perhaps the worst body in the history of international hoops.” He fouled out quickly.

The Bucks, playing without Sidney Moncrief, Ricky Pierce, Craig Hodges, and John Lucas, demolished the Soviets inside. Terry Cummings, Jerry Reynolds, and Jack Sikma led the way for Milwaukee. The Bucks scored and rebounded at will. They also forced the Soviet offense into taking a bunch of desperate jumpers that didn’t fall. At one point, the Bucks led by 48. When Harris pulled his starters, the Soviets stormed back to within 10 in the fourth quarter. The final was a slightly more dignified 127-100.

But the main thing is that it was fun. The crowd was raucous and celebratory. According to the Washington Post, “The top item at concession stands was a red tank-top emblazoned with the letters CCCP.”

The tournament continued in various forms through 1999. The hoops landscape is obviously very different these days. For one, Taco Bell is now the NBA’s main fast food sponsor. For another, as the league itself has become more global, goodwill exercises like the McDonald’s Open have grown somewhat redundant. In the context of basketball history, 34 years is a long time. Only two players in the current NBA finals were even alive for that initial tournament: Bucks forward P.J. Tucker, and Phoenix guard Chris Paul.

Alexander Gomelsky

I didn’t know much about Alexander Gomelsky before writing this — but what a fascinating guy. First of all, he came from obscurity in a tiny Russian town to become the widely accepted father of Soviet hoops. He won everything there is to win as a coach, then became the president of CSKA Moscow club and ultimately the Russian Basketball Federation. He’s in all the Halls of Fame basketball has to offer.

Also fascinating: Gomelsky was reportedly barred from coaching the Soviet team at the 1972 Olympics in Munich because he was Jewish, and the KGB feared he would defect, and confiscated his passport. (The Soviet Union would win gold without him in one of the most controversial basketball games in history.)

Gomelsky did not win an Olympic gold medal until a year after the McDonald’s Open in Milwaukee, when the USSR ousted the United States en route to its victory at the 1988 Seoul games. This would be the Soviet Union’s final basketball gold. The USA’s embarrassing bronze medal finish led FIBA, basketball’s global governing body, to end its ban on NBA players in international tournaments. Four years later, we got the Dream Team.

Related Reading

If you have a couple of free hours, you can watch the game here:

Not only will you get a fully hyped Dick Vitale talking about Soviet players as if they are Duke upperclassmen, but it’s just a fun, immersive timewarp. Cheryl Miller is the sideline reporter. The graphics are excellent.

And even if you don’t watch it, I would still recommend reading this great contemporaneous piece by Jack McCallum. The Washington Post recap also had some nice detail and quotes.

Finally, here’s a fun piece from the LA Times about Sarunas Marciulionis and his family. While he was playing with the Warriors, his wife Inga, also a former USSR national team player, enrolled at Merritt College in Oakland and became a superstar for the basketball team — lighting up community colleges around the Bay Area. Inga and Sarunas have since divorced. He went back to Lithuania (where he recently won, and then declined a seat in the European Parliament) and she is now a professor of Kinesiology at Merritt.