The Boy With the Vengeful Heart

How North Korea's first Olympic gold medalist set off a controversy by telling the truth in Munich, 1972.

Welcome to Sports Stories, a newsletter that explores sports and history at the intersection of everything. If you’re not already a subscriber, you can sign up here.

There were no summer Olympics in 2020. Not that anybody noticed. Of the many things we missed and the many lives we lost, what’s an Olympiad anyway? The Tokyo games have been rescheduled, but I’m skeptical about that too. Do we really think that by this summer, we’ll be living in a world where a massive international sporting tournament makes any kind of sense? Then again -- maybe sense doesn’t matter. After all, there’s a lot of money on the line.

I’m already getting off topic. The other thing about the Olympics is that they just don’t matter like they used to. The world’s attention is harder to focus in a single direction for an entire month; our interests are too diffuse and our politics are too convoluted for the games to hold the symbolic power they once did. Our most dramatic international hostilities play out not in grand symbolism but in low key trade wars and, quite literally, on the internet. The mystery is gone. We know the enemy -- and she’s not a Chinese gymnast or a Russian shot putter. If anything, the enemy looks increasingly like the institutions that prop up the games themselves: like the crooks who run the IOC and are constantly getting slapped on the wrist for their corruption but keep on being corrupt anyway; like the local and national governments who choose again and again to build temporary sports infrastructure instead of making permanent investments in their communities.

I’m even further off topic now. I actually love the Olympics. I love the stories (no surprise there) and I love learning about all the different sports. I love how much it matters to the athletes who work their lives for a specific flavor of glory that, for all the nationalism and all the complications and all the bullshit, is truly theirs and theirs alone to hold and to treasure. The Olympics matter a ton to the people playing the games.

They mattered a ton to Ri Ho-Jun. Ri was a marksman and a part of the very first Summer Olympic delegation from North Korea at the 1972 games in Munich. Had it been any other year, Ri’s story might have lingered in the public consciousness a little bit longer. But the Munich games were marred by the murder of 11 members of the Israeli delegation and a West German police officer by the terrorist group Black September. They were haunted by the echoes of Hitler’s 1936 games in Berlin. If you remember the 1972 Olympics beyond the attack, you might remember swimmer Mark Spitz setting a record for career gold medals; you might remember the controversial basketball final between the United States and the Soviet Union.

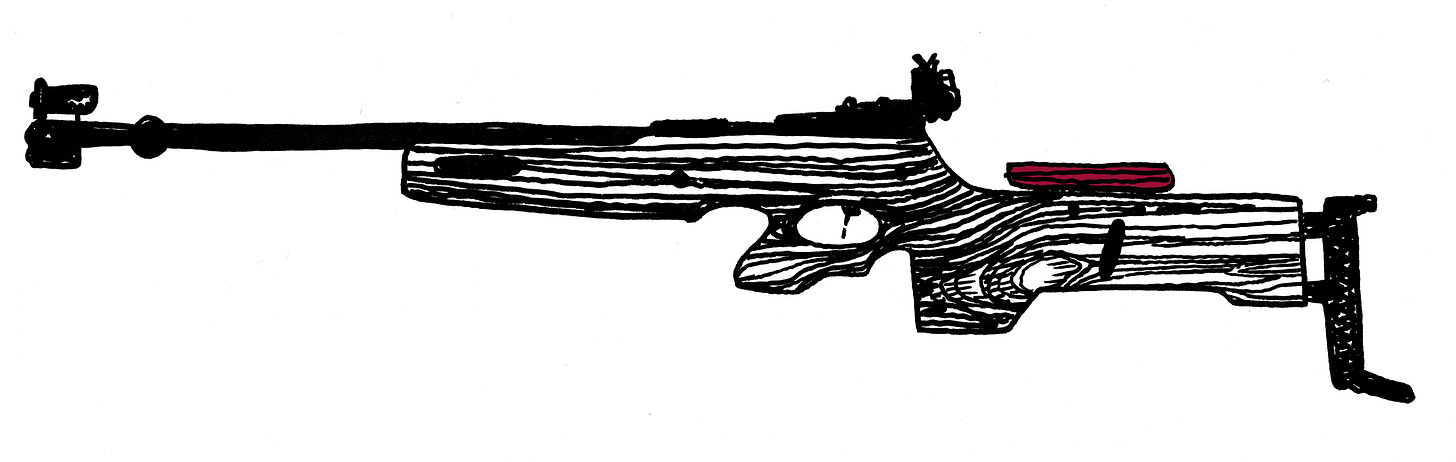

Ri was only 22 years old when he landed in Munich to compete in the 50 meter rifle prone event. In case you aren’t familiar with the world of shooting sports, this event requires the shooter to lie down with a .22 caliber rifle, and fire off 60 shots at a target 50 meters away. The target is a series of 10 concentric circles, the smallest of which is the size of a dime. You’re awarded 10 points for hitting the bullseye, 9 for the next circle, and so on.

The thing about shooting is that it’s the only Olympic sport where the equipment is also a weapon of war, which means that competition is inextricably linked with military service and culture. That was especially the case in North Korea, where people did not own recreational guns like they do in the United States and where military service was both compulsory and a key part of the national identity. It’s also worth reminding readers here that the national identity of Kim Il-Sung’s North Korea in 1972 was defined in part by a deep hatred of the United States of America.

All of this weighed on Ri Ho-Jun in Munich, where he and his cohort were led to believe that their success on the field of play would be a reflection of their country’s greatness. The personal details of Ri’s life are sketchy -- most of the sources out there consist of articles published by North Korean propaganda publications on the internet. Some of them I also had to run through Google translate. The resulting text was a strange blend of outrageous overwriting and choppy translation. Sometimes it could be hard to tell where the glorifying ended and the stilted voice of the algorithm began.

Regardless, it seems fairly certain that Ri was marked by his country’s politics long before he put on the military uniform himself. His father was killed by American troops early in the Korean war. Ri grew up with his mother in a small mountain town near the Sea of Japan, an “ordinary peasant” with -- per one article -- “a vengeful heart.” He had an aptitude for math and geometry that quickly translated when he picked up a gun.

When the military discovered his talent, Ri was plucked to be part of the country’s sports program. He was the youngest member of the shooting team, but he was a willing student and a fast learner. He arrived in Munich completely unknown to his competitors and totally oblivious to the norms of international sporting events. It seemed likely that Ri would return to North Korea just as obscure as when he arrived. But that was not the case. At their best, the Olympics are a perfect stage for underdog stories.

During practice rounds before his competition, Ri was impeccable. Then, in the actual competition he was equally dominant. It appeared that the only person standing in his way was an American shooter named Victor Auer. Auer, like Ri, was a product of his circumstances. He was an all-American kid from Southern California who learned to shoot as a boy, then competed as a UCLA student and Air Force reservist. He was apparently also a writer for cowboy TV shows like Gunsmoke.

As the competition came to an end, it appeared that Auer had locked up the gold medal. His score came back at 598 out of a possible 600, which would be nearly impossible to beat. That meant he hit the dime 58 times out of 60 shots. Ri’s score initially came back at 595. But after looking at Ri’s target, the North Korean delegation requested a manual review. (The event was scored electronically but an appeals process existed where human judges could examine the targets through a microscope to decipher the precise location of the bullet holes.) The review took hours. Ri waited. Auer celebrated -- certain that he had won.

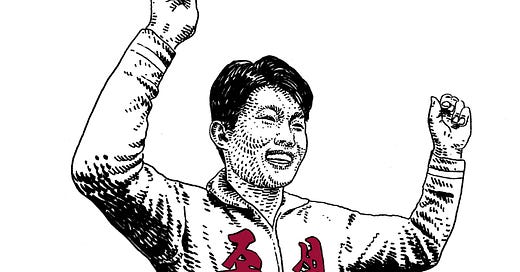

But the result came back otherwise. It turned out that Ri had scored a 599. That meant he had only missed the bullseye with a single shot. He defeated Auer, won North Korea’s first ever gold medal, and set a new world record in his event. “Who ever heard of this guy?” Auer reportedly said.

But this was only the beginning of Ri’s story in Munich. At his press conference following the medal ceremony, Ri ensured that for at least a moment, people would remember him as more than just a gold medalist. What exactly he said was up for some debate, even at the time, but the United Press International correspondent in attendance quoted him this way:

“Our Prime Minister, Kim Il-Sung, told us before we left home for the Olympics to shoot as if we were fighting against our enemies, and that’s exactly what I did.”

Unspoken, of course, was who the precise enemy of North Korea was. Unspoken, of course, was which country’s airplanes had dropped the bomb that killed Ri’s father in 1950. But the full extent of the truth did not need to be spoken in order for Ri to shatter the false sense of decorum that guides the games.

After the press conference, there was a sudden storm of anger and protest by other delegations. The great lie of the Olympics, the great animating principle, is that when the torch is lit and the games begin, the politics are left behind. It’s okay for sports to be a proxy for war and it’s okay -- even glorious -- to celebrate the vanquishing of enemies on the field of play, so long as you maintain the illusion that it’s only a game. Ri had shot another bullseye right through this lie.

It was such a flimsy and disingenuous fiction anyway. Could these men who operated a sport that consisted literally of shooting guns really be affronted by the fact that Ri had reminded them of what guns are actually for? Many had been in Mexico City four years earlier where the government massacred student protesters to clean the streets and put on a good face ahead of the competition. And all of them would still be in Munich five days later when the terrorists entered the Olympic Village.

Before the controversy could get out of hand, the North Koreans called a second press conference in which Ri claimed he had been misunderstood and that he made no such comments. But according to the UPI report, by that point North Korean officials had already confirmed the anecdote -- that Kim Il-Sung had beseeched his team to “aim as though you’re shooting at your enemies.”

Ri’s story appeared on the cover of the next day’s issue of the American military newspaper Stars and Stripes below one about Mark Spitz and another about Nixon’s plans to end the draft. On page 2 of the paper, Ri’s photo was printed above a bolded caption that read “Vengeful Victor.” Ri may have been a boy with a vengeful heart, and he may have been a vengeful victor to the American press, but he returned to North Korea a hero.

After the 1972 games, Ri was awarded the Soviet Union’s highest sporting title, Merited Master of Sport. He continued to compete internationally for another decade or so, including at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal. He also reportedly became a private shooting instructor and then personal bodyguard for the future dictator Kim Jong-Il.

Ri has now lived long enough to see the event that made him famous become obsolete. Before the Tokyo games were delayed due to the global pandemic, the men’s 50 meter prone rifle event was removed from the slate of competition.

Related Reading

The most detailed story we could find on Ri’s life came in Korean from a website called Jajusibo.com. Here’s a link to the translated version. Jajusibo appears to be a pro-North Korean propaganda outlet operating out of South Korea. The South Korean government had shut down a previous version of the site in 2015. Here’s another short item on Ri from the Korean Friendship Association USA, a group dedicated to supporting the DPRK from abroad.

Contemporaneous English language newspaper coverage of Ri’s victory tended to focus on the controversy surrounding his post-game press conference. “N. Korean Wins, Errs” went the New York Times capsule headline. Ri’s victory also fell into a larger pattern of American athletes and teams grumbling about unfair officiating at the Munich games. Earlier I mentioned the gold medal men’s basketball final between the USA and Soviet Union. In that game, the final play was repeated three times amidst timekeeping and referee chaos and ultimately resulted in the USSR winning it on an absurd play.

Finally, if you’re interested in learning more about North Korea or just picking up a really good book, I recommend Barbara Demick’s Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea, which is one of the most powerful pieces of nonfiction, history, reportage, and empathetic storytelling that I can remember reading.

Victor Auer’s Feelings

Following the end of the Munich Olympics, the Los Angeles Times ran an interview with the man Ri Ho-Jun bested in the 50 meter prone rifle event: Victor Auer. The article was so bad, so tasteless, so painfully unnecessary that I can’t help but share it with you all. The premise is that Auer was upset about the media’s coverage of the Munich games. Here are two separate quotes from the runner up, speaking less than two weeks after the attack, botched rescue, and massacre:

“They overemphasized the bad and said practically nothing about the good things that happened. It hurt quite a bit.”

And,

“Sure, there were six or seven incidents that were a fiasco, but that was only a small number.”

Anyway, here’s the story in full:

Reminders!

Sports Stories is completely free, but we really do appreciate your voluntary support to bring these words+pictures to your inbox every week. We’re still offering a complete set of five postcards featuring Adam’s art to our first 100 paid subscribers — learn more here.

And if you are among the paid subscribers who has yet to fill out our survey, please do so today so we can get thank you gifts in the mail as soon as possible.

As always, thank you for reading Sports Stories. We’ll see you next week.