The Bright Side of Fights

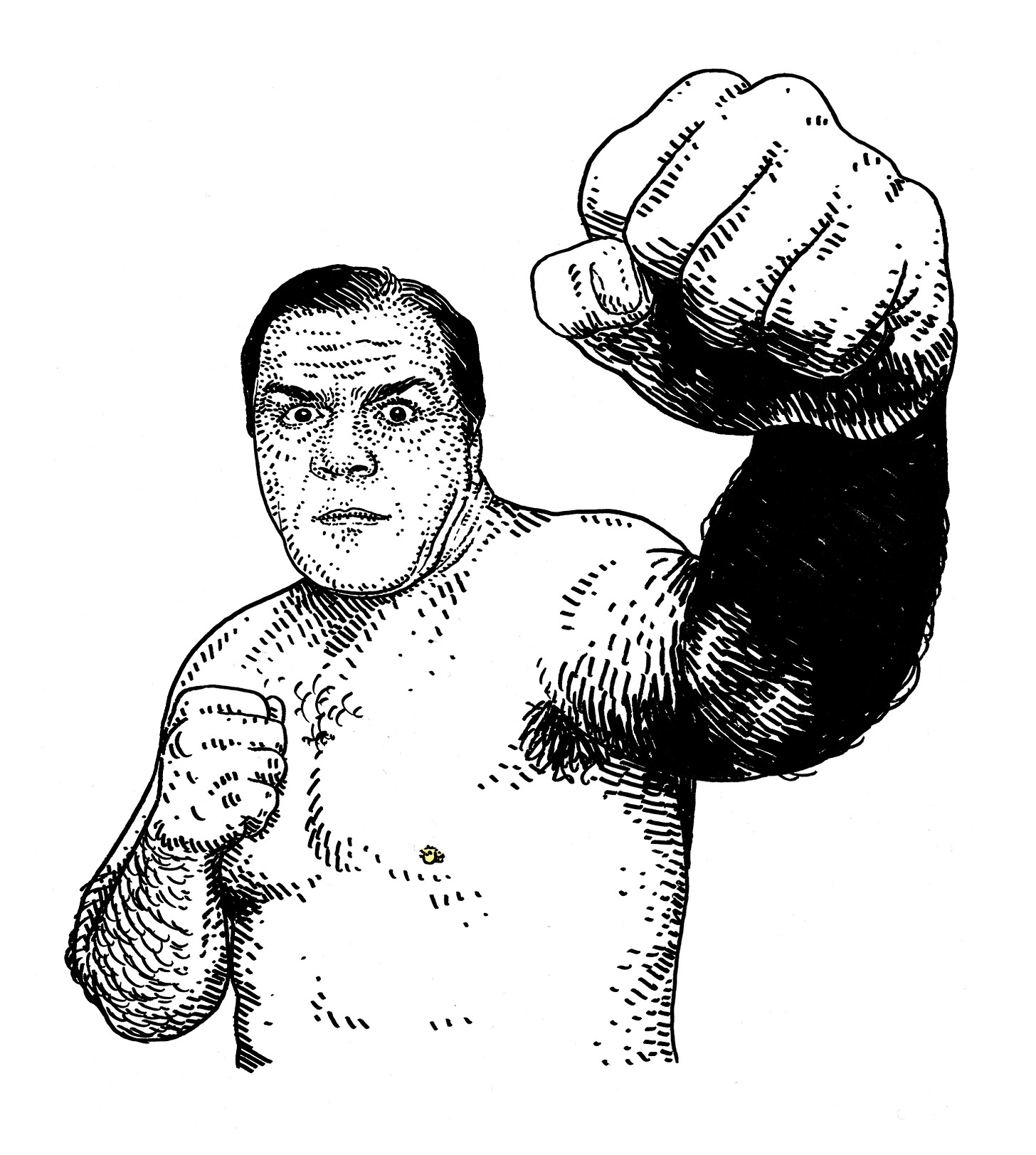

Lenny McLean, aka "The Guv'nor," was England's unlicensed boxing king.

Welcome to Sports Stories, a publication at the intersection of sports and history. Sports Stories is written by Eric Nusbaum, illustrated by Adam Villacin, and delivered to your inbox every Tuesday.

If you’re not already a subscriber, please sign up here — we have both free and paid options. Paid subscribers are entitled to our eternal gratitude as well as cool swag including postcards featuring original art by Adam.

"You've got to fight to get anywhere. If you don't fight, you're just one of the crowd and one of the crowd don't get nuffink.

That was how Lenny Maclean talked, and it was also how he lived. He was mean and tough. Violence was the one constant in his life from the time he was a boy in East London through his rise to fame as a bouncer, unlicensed boxing legend, and finally, actor. Violence oozed from him. Violence shaped him.

Lenny’s stepfather beat him and his siblings brutally as a boy.

“He broke my legs when I was five and broke my jaw when I was six. When I was seven, he broke all my ribs. He bashed me right about until I was 12.”

The stepfather went on beating him until one of Lenny’s uncles stepped in and put an end to it with a beating of his own. This uncle was a highly respected gangster. Lenny’s career opportunities were not extensive. He went into the family business.

He grew up to be tough and angry and also very huge. He spent a lot of his time fighting and drinking, not necessarily in that order. He once bit a man’s nose off. Late in his life, Lenny would star in the movie Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels as a gang enforcer named Barry the Baptist. But the blood and guts of his real life was not stylized by a famous director or punctuated by clever dialogue. He was in and out of jail for years.

In the late 1960s, Lenny fell into the world of unsanctioned boxing. A lot of these fights were of the bare-knuckle variety. Bare-knuckle boxing isn’t illegal because it’s more dangerous for fighters. (It actually might be safer; gloves are heavy and the padding they offer allows fighters to punch harder without fear of breaking their hands; those heavier, harder punches can then lead to more brain injuries.) Bare-knuckle boxing is illegal because it’s generally bloody and horrible. The gloves allow us to tell ourselves that what we’re watching (or doing) is not some primal act; that it’s a refined sport, not a mere street fight.

Lenny became an icon because he knew it was not different. He saw fighting for what it was. He weighed 280 pounds. He fought for fun and for pride and for money. He fought all the time at work as a bouncer. In the late 1970s, Lenny had a series of bouts against a fellow tough guy named Roy Shaw. Shaw had allegedly fought a little as a licensed pro, but like Lenny, his criminal record prevented him from making a career of it.

It’s worth noting here that the “record” as it exists with lives like Lenny’s and Roy Shaw’s is half myth and half word of mouth. Roy Shaw, the story goes, was a wild maniac. In his younger years, he was an armed robber. Once, while serving time in prison, he yanked one of the legs off his cot and used it to beat the door of his cell until it opened and he could walk right out. He palled around with notorious London criminals like Ronnie and Reggie Kray.

Shaw was also a vicious boxer. But Lenny, younger and taller, was an extremely proud man. Especially when it came to fighting. He was not pleased when in his first fight with Shaw, he found himself out of shape and unable to inflict any damage. He wrote in his autobiography that he was exhausted, but also not particularly injured. He kept running his mouth right up until the referee blew the whistle and called it for Shaw.

Before the rematch, Lenny decided to actually train for the first time in his life. On his first day, he went with a friend to a park to jog. They intended to run one mile. Halfway in, his friend collapsed. They walked the rest of the mile and then went to a pub and got drunk. But little by little, Lenny got in shape. He went to school with a well known British boxing trainer named Freddy Hill, and sparred with a local middleweight named Kevin Finnegan. Finnegan was in training to take on Marvin Hagler. (He would lose, but respectably.)

The next time Lenny and Shaw fought, there was a crowd of 30,000 on hand. There were TV cameras. It looked like any blockbuster title fight—only a degree sketchier. There was no governing body, no belt on hand. The ring girls—normally just scantily clad—were simply topless. You could argue that this was boxing at its most honest with itself.

Before the match there was a brief and absolutely hilarious interview in the ring in which an announcer asked Shaw about his nickname.

“Why are you called the Mean Machine?”

Shaw shrugged.

“Well, ‘cause I’m mean.”

He was not mean enough. Finally in shape and having now picked up some of the fundamentals of boxing, Lenny swarmed Shaw and knocked him down immediately. Then he gave him a few kicks to the ribs before the ref was able to step in. Shaw survived the knockdown and fought his way into the second round. Then, Lenny punched him clear through the ropes and out of the ring. It looked like something from a cartoon.

There was a third fight, which Lenny won by first round knockout, sealing his reputation as the meanest unlicensed fighter in London, aka The Guv’nor. But winning fights didn’t change much about Lenny’s life. He continued to work as a bouncer. In the 1980s, he booted some rowdy bachelor party revelers out of a club and then one of them came back and shot him the arse (his words). Soon after that, he gained some international notoriety for a bare-knuckle fight against a fellow named Brian “the Mad Gipsy” Bradshaw. Lenny put him into a coma, and the footage found its way onto the Today Show.

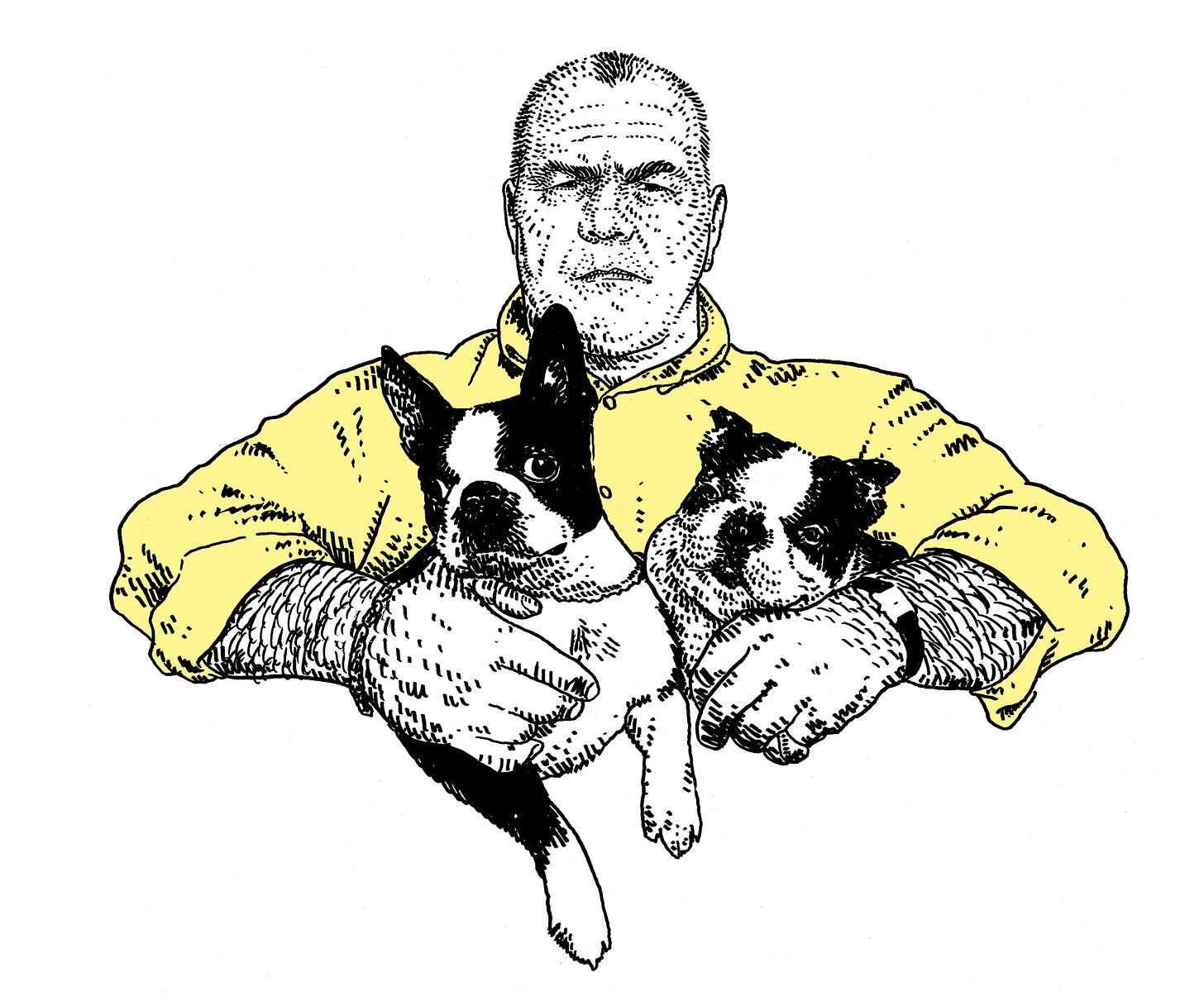

According to Lenny’s daughter, he began to visit Bradshaw in the hospital in the days after the fight. The two became good friends. This was the side of Lenny McLean most people didn’t see.

In the early 1990s, Lenny violently removed a man named Gary Humphries from one of the clubs he was working; Humphries was drugged out, hysterical, and naked on the dance floor. By most accounts, Lenny slapped him hard with the back of his hand, dressed him in some clothes he scrounged from somewhere, and tossed him into the street. The next morning, he got a call that Humphries was dead.

Lenny was charged with murder, which was then adjusted down to manslaughter. At his trial, it was revealed that Humphries had not in fact died immediately after getting his jaw busted by Lenny. In fact, he had continued on fighting and carousing through the London night for hours afterward. One expert witness testified that the most likely cause of death was a stranglehold used on Humphries by the police later in the evening. Lenny was found not guilty.

In his book, Lenny wrote that upon hearing the verdict, he burst into song in the courtroom, belting out Monty Python’s “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.”

Lenny McLean spent the 1990s working off and on as an actor. He appeared in some TV shows and films before landing his breakout role in Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. He had made the transition from a life of real violence to a life of pretend violence. During the filming of Lock, Stock, he fell badly ill and was diagnosed with lung cancer. The cancer metastasized quickly. He died in 1998, before the movie was released.

In the section of his autobiography where he wrote about Roy Shaw, Lenny summed up the reality of combat sports—licensed or unlicensed—very neatly.

“It’s all about money in this game. In the ring or on the cobbles we hate each other. We want to inflict real damage, break bones, get as close to murder as we can. Yet if I bumped into Roy Shaw in the street I wouldn’t bite lumps out of him. I’d give him a nod, nothing else, because we aren’t in love with each other.”

Related Reading

Lenny wrote an autobiography called The Guv’nor that is very entertaining and also requires an East London slang dictionary to be properly understood.

His daughter Kelly wrote a book called My Dad the Guv’nor with a lot of insight into his personality as well. Kelly said that after his death, doctors told her they thought he had been suffering from undiagnosed bipolar disorder.

His son Jamie also directed a documentary film about his father called The Guv’nor, which you can rent for a buck on Amazon. (I haven’t watched it in its entirety.)

To read about his battles with Roy Shaw, I recommended this piece from Fightland by Alexander Reynolds. For another good quick overview of Lenny’s life, I’d check out this story by Matt Stagliano of Skillset Magazine.

Finally, there’s tons and tons of video of Lenny on YouTube. It’s an easy rabbit hole to get lost in.

Thanks for reading Sports Stories. We’ll see you next week.

Fantastic storytelling here. It's fascinating to me how contemporary the story of Lenny Maclean is -- feels like a story that could be 80 years old. Instead it's from the late '70s and Lenny found his way into Guy Ritchie's sphere. Great job -- thanks for telling this story!