Welcome to Sports Stories, an illustrated newsletter at the intersection of sports and history. If you’re not already a subscriber, please consider joining up here — we have both free and paid options.

If you’re a longtime reader, or just enjoy this post, please consider doing us the favor of sharing Sports Stories. You are the reason we do this, and also happen to be our best (and only) marketing system.

In The Great Gatsby, the first time the narrator Nick Carraway meets Jay Gatsby, they talk about their experiences in World War I, and reminisce on “wet, grey, little villages in France.” Then Gatsby invites Nick for a ride on his hydroplane.

The Great Gatsby is, among other things, a book about money. And what better symbol could there be of high society luxury and sporting fun in 1920s Long Island than a boat so fast that it literally flies atop the water?

Joe Carstairs did not live in Long Island at the time, but she came from money (a lot of money), and it was money that allowed her to become a famous boat racer; money that enabled her to become known as “the fastest woman on water.”

Carstairs had that money, but not much else as a child. She was born Marian Barbara Carstairs in London, England in 1900. Her mother was an American oil heiress who battled addictions to drug and alcohol and chewed through one husband after another: first there was Carstairs’ father, a Scottish military officer, then there was another officer named Francis Francis, then a French count, and finally, French-Russian physician named Serge Voronoff who became infamous for grafting testicular tissue from monkeys and apes onto men as a form of “rejuvenation.”

But Carstairs didn’t personally deal much with these husbands. Nor did she deal much with her mother for that matter. To the old folks in her life, she was an odd and independent and recalcitrant child. So the old folks sent her out of sight to boarding school in Connecticut when she was just 11 years old. High society didn’t know how to cope with a little girl like her, because she wasn’t really a little girl at all.

The best source of information on Joe Carstairs is Kate Summerscale’s biography The Queen of Whale Cay. And I think it’s worth going ahead and quoting from the very first page of that book, because it is insightful and beautifully written.

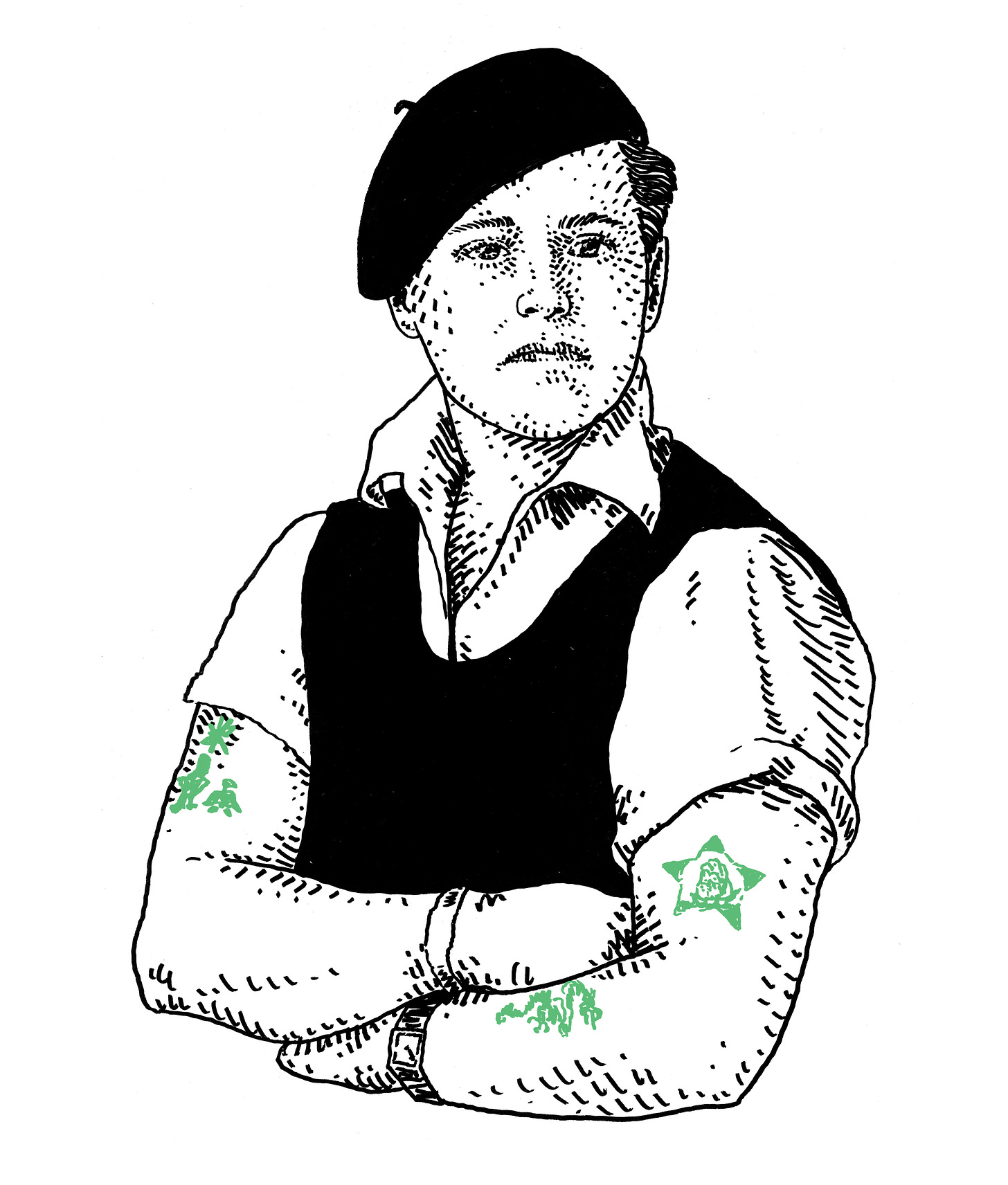

There you have it. Joe Carstairs left names like Marian and Barbara behind. She dressed as a man and got cool tattoos and openly had affairs with women. During World War I, she drove an ambulance in France for the Red Cross. After the war, her mother died, and Carstairs briefly married a childhood friend in order to access some of her inheritance. She used it to open a limo company called X-Garage with all-female drivers and mechanics. A few years after that came an even larger inheritance upon the death of her grandmother. This was when Carstairs bought her first boat.

Carstairs spent the late 1920s building increasingly fast hydroplanes, and winning many races. She was addicted to the sensation of speed, and she said she raced boats in part because she felt that they felt faster than cars or airplanes. She was also a true eccentric. A girlfriend gifted her a small doll, and Carstairs became famously attached to it, giving it the odd name of Lord Tod Wadley, buying it custom tailored clothes, and carrying it with her everywhere for the rest of her life. As a tribute to her late mother, Carstairs named many of her boats Estelle -- only to later learn that her mother went by Evelyn.

For Jay Gatsby, the hydroplane was a status symbol. For Joe Carstairs, it was life itself. Of course, unlike Jay Gatsby, Joe Carstairs was born rich. And she was not prone to worrying about status or symbols or anything like that anyway. She raced until she had enough of racing. Then she bought an island and decided to build an empire.

In 1934, Carstairs left racing behind and moved to Whale Cay, a 700-acre island in the Bahamas. She would spend the next 40 years living there as a sort of imperialist queen alongside her doll, Lord Tod Wadley. She built a great mansion and a church and a lighthouse and maintained an agricultural operation with hundreds of employees who she treated like subjects. She entertained famous guests and countless lovers. (Sometimes, like in the case of the actress Marlene Deitrich, these were one and the same).

This isn’t to say that Carstairs stopped boating. She continued to love the water. Once during World War II, she even rescued a crew of American merchant marines whose ship had been sunk by a a German U-Boat in the Caribbean.

Carstairs left Whale Cay in the 1970s for South Florida, where she lived out the rest of her life in relative quiet. She died in 1993, and was cremated alongside Lord Tod Wadley. Both of their ashes were buried in Long Island.

Related Reading

For more on Carstairs, the real definitive source is the aforementioned book The Queen of Whale Cay by Kate Summerscale. Cool fact about that book: it grew out of Summerscale’s work as an obituary editor at The Telegraph. When Carstairs died, one of her goddaughters sent Summerscale information about her life — and after writing the obit, Summerscale decided there might be more there, so she started digging. It’s a good thing she did.

Whale Cay itself was put on the market recently for $20 million. Here’s a story about it from Forbes.

Finally, here’s an account about the merchant marine rescue Carstairs made during WWII from a website about shark attacks. (One of the survivors of the U-Boat attack was indeed bitten by a shark in the arm, and later died of the ensuing infection.) This contains some good primary sources too.

Doc Voronoff

Earlier we mentioned that Carstairs’ mother Evelyn was married for a time to a Doctor Serge Voronoff. While he isn’t a “sports story” technically speaking, Voronoff was a fascinating dude. His insane medical practices (once again, that’s grafting bits of ape testicles into human scrotums) were a huge sensation in the 1920s. Supposedly, the ape specimen would fuse with the human tissue around it and rejuvenate old men. Thousands of men got this surgery, and Voronoff even raised his own monkeys for the express purpose. It’s absurd and also horrifying to think about. Which is perhaps why the poet ee cummings wrote about it in a poem:

Thanks for reading Sports Stories. We’ll see you next week.