The Forgotten Surf Legend Who Died in a Flu Pandemic

George Freeth is responsible for a lot of what we now think of as California beach culture.

George Freeth didn’t actually give us California. California was stolen by the Spaniards from the native people who lived there, then it became part of Mexico after it achieved independence from Spain, and finally it was stolen again from Mexico by the United States.

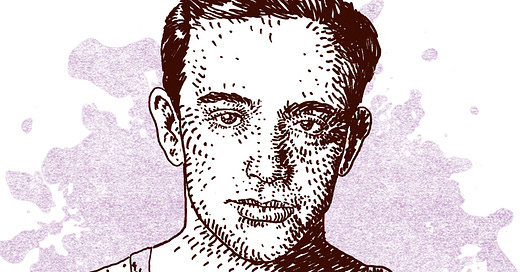

But George Freeth, as much as anybody, gave us the idea of California. The place that exists in the minds of people who have never set foot on a sandy beach. George Freeth gave us the opening credits of the The O.C. and the Beach Boys and Baywatch. He was, as responsible as any single person, for California beach culture as we know it -- from the lifeguard tower to the surfboards. He was also one of the great athletes in American history. He has also been largely forgotten. This might be because in 1919, a global flu pandemic struck him down at just 35 years old.

Freeth was born in 1883 in Hawaii to mixed ancestry -- part native, part European. When he was a kid growing up beside Waikiki Beach, surfing was still a relatively obscure Polynesian tradition. For generations it had been stifled and suppressed by missionaries and colonizers as frivolous and meaningless. But Freeth was deeply in touch with the water. He was a great swimmer and diver in a place that was famous for producing great swimmers and divers. But above all, he was a masterful surfer.

When he was a teenager, Freeth encountered an American adventure writer named Alexander Hume Ford. Ford wanted to write about Hawaii, and he wanted to learn to surf. So Freeth taught him. (Ford loved surfing so much, he decided to start what would become the iconic Outrigger Canoe Club.) Ford also introduced Freeth to another writer -- Jack London. Freeth taught London to surf too. He was good at teaching, endlessly patient, and intuitive. And the writers saw something in him. Freeth was quiet, but he had a restlessness of spirit that they could relate to. He had an independence about him, and a meditative way of talking about the water.

The water was religion to Freeth. He understood both what it could give and what it could take away. He wanted the world to understand this too. After getting to know Ford and London, Freeth decided he would make his way to California.

When George Freeth arrived in 1907, Los Angeles was still coming into its own. The city was in one of its periodic booms, and a lot of the booming was happening on the coast. On the beach south of Santa Monica, an insane, bearded rich guy named Abbot Kinney was literally recreating Venice, Italy -- and succeeding. A dozen miles south of Venice, the tycoon Henry Huntington was developing his own beach resort, and delivering beachgoers there via the vast privately owned transit system he owned.

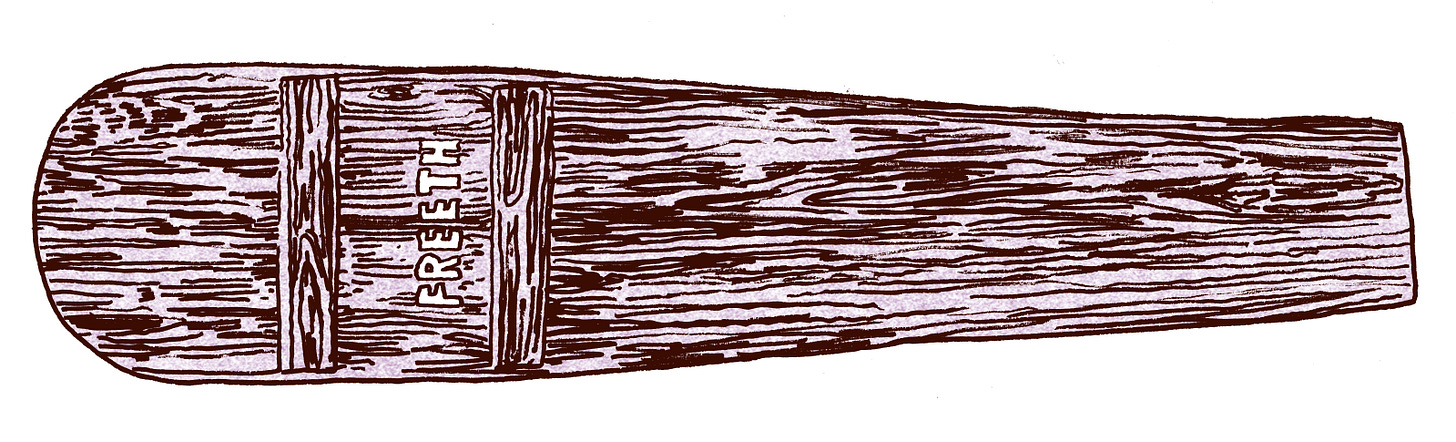

Both men put Freeth to work. He was a one-man tourist attraction. He gave surfing and diving demonstrations, and quickly elevated surfing’s place in the popular consciousness. Then, when he wasn’t demonstrating the beauty of water sports, he was helping enact new standards for water safety. One of the great obstacles to beach tourism in early twentieth century LA was that people kept drowning. Sometimes, even the lifeguards themselves drowned.

This happened for two reasons: first of all, nobody really understood how the ocean worked. Lifeguards patrolled the beach in little boats, which were useful for helping sailors who capsized far off the coast, but not so helpful for saving drowning swimmers. When attempting to rescue drowning swimmers, the lifeguard boats often capsized themselves in the heavy waves and shallow water. Another example: until Freeth arrived, it was commonly believed that rip tides actually dragged swimmers *under* water, and that swimming furiously was the only way to avoid certain death. Freeth explained that rip tides in fact drag swimmers *out* and that to fight them is futile. Lifeguards could in fact use the tide to help them reach the trapped swimmers before pulling them out.

It is worth noting here that the definitive scholarship on George Freeth was conducted by Dr. Arthur C. Verge. In his work, Verge paints a vivid portrait of Freeth, and reconstructs early twentieth century Los Angeles in wonderful detail. For example, Verge hones in on Freeth’s obsession with water safety:

Those under his tutelage, whether male or female, were expected to become "watermen." The young Hawaiian's vision of a true "waterman" was a person who was one with the ocean. Freeth expected his pupils, after diligent training, to be able to safely swim, paddle, and row through treacherous surf. Additionally, he taught his future lifeguards the latest techniques and treatments in medical first aid. "Innovation" and "efficiency" were his watchwords; he encouraged people to think "outside the box" when it came to saving lives. Following his example, several of Freeth's pupils took up distance sand running, ocean swimming, and surfing to better acclimatize them selves to the rigors of the ocean from which they were now expected to protect swimmers.

What Freeth was doing was in fact creating the model for the first modern lifeguard crews. His work earned him all kinds of accolades locally -- and when he single handedly saved seven fishermen from drowning off the Venice Pier in 1908, Freeth was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

It’s sort of ironic that Freeth, this pure spirit who loved nothing more than the ocean, found his work sponsored by a pair of greedy real estate developers. But that’s how it was: Kinney and Huntington could not have grown their beach resort empires without George Freeth. And George Freeth would not have been able to reach as many beachgoers and spread the gospel of the waves if Kinney and Huntington weren’t desperate to draw people to the ocean. It was not a natural fit, but it worked.

Freeth settled into a spartan life, bouncing between Venice and Redondo Beach. He never cared much about anything but the water, anything but his work. Sometimes he neglected his life in other ways -- he had very few material goods, and even less when it came to savings. He swam competitively and nearly competed in the Olympics in 1912 but was derailed by the fact that he had once been paid for what Verge refers to as “aquatic activities” meaning that he was ineligible. (The scourge of “amateurism” is nothing new.)

However, one of Freeth’s proteges and friends from back in Hawaii went off to Stockholm with the American delegation: a fellow surfer named Duke Kahanamoku. Duke would go on to win a bunch of gold medals as a swimmer and, in the years after Freeth’s death, become the global face of surfing.

Freeth meanwhile, took a job down in San Diego, where the beach scene was burgeoning. He had hard times, and had to work a retail job one winter. But as San Diego filled with military personnel during World War I, the beach seasons became increasingly challenging and deadly -- and Freeth became increasingly vital to maintaining safety. He worked the length of Ocean Beach in a motorcycle, patrolling the shoreline and watching the waves.

The city was overloaded with young recruits. Barracks were full and bases were overcrowded. Young soldiers were being housed anywhere the government could find room. This was wartime, and sacrifices had to be made. But there were also risks. In 1918, the world was consumed by a deadly and fast-spreading strain of the flu. The first instances in the United States came at a military base in Kansas. (Of course the public was not informed of this.) It did not take long for the flu strain to spread to San Diego, where George Freeth was in close contact with the teeming masses of soldiers: walking among them, swimming with them, pulling their drowning bodies from the ocean.

More than 50 million people died in the pandemic, and one of them was George Freeth. The paragon of physical fitness. The ultimate waterman. He caught the flu in early 1919, and by April, he had faded away. His ashes were returned to Oahu, and buried in the family tomb not far from Waikiki Beach and the waves that had raised him.

Related Reading

This volume of Sports Stories (and anything else ever written about Freeth) basically owes everything to Arthur Verge’s work, which originally appeared in California History but was reproduced on KCET’s Lost LA website. Verge also recently showed a short film that Freeth appeared in called “The Latest in Life Saving” at a talk in Redondo Beach.

I also enjoyed this 2002 story from the LA Times on Freeth by Cecilia Rasmussen.

Going back to the days Freeth was actually around, Jack London actually wrote about him in a fair amount of detail in an essay called “Riding the South Sea Surf.” It’s a pretty entertaining but somewhat tossed off piece. Here’s how he describes his first encounter with Freeth:

Shaking the water from my eyes as I emerged from one wave, and peering ahead to see what the next one looked like, I saw him tearing in on the back of it, standing upright on his board, carelessly poised, a young god bronzed with sunburn.

Busted

In 2008 a bust of Freeth was stolen off the pier in Redondo Beach. Nobody ever figured out who took it. (The best guess is that it was melted down for the bronze.) Anyway, a local businessman named Bob Meistrell (he founded the surf company Body Glove and literally invented the neoprene wetsuit) unsuccessfully put up a $5,000 reward for information leading to the bust’s whereabouts. When it was clear that the bust was gone forever, Meistrell led the effort to replace it using a mold that had been preserved by the Redondo Beach Historical Society. The new Freeth bust was mounted in 2010, and has lived in peace since.

The Duke

I mentioned him briefly above, but it’s worth learning to love and appreciate the life of Duke Kahanamoku on his own terms. Duke had one of the most interesting lives of any athlete ever -- he is a man worthy of like a whole year of Sports Stories newsletters alone: world class swimmer, surfing icon, defendant in a pivotal Supreme Court Case, innovative lifeguard, actor, and more.

David Davis’ biography of the Duke, Waterman, is an awesome read.

Book Stuff

STEALING HOME comes out two weeks from today! You can still pre-order and get a custom baseball card, too. (I literally just bought some more envelopes yesterday.)

Just reply to this email with proof of purchase. More info, as ever, at

This has been Vol. 21 of Sports Stories by Eric Nusbaum (words) and Adam Villacin (art). If you have any questions, comments, or concerns, please reply to this email or contact enusbaum@gmail.com. We’d love to hear from you.

Sports Stories is 100 percent free. If you enjoyed this week’s newsletter, and want to show your appreciation, the best way to do that would be to sign up, share it on social media, or forward it to someone you think might enjoy it too