The Girl Hawk

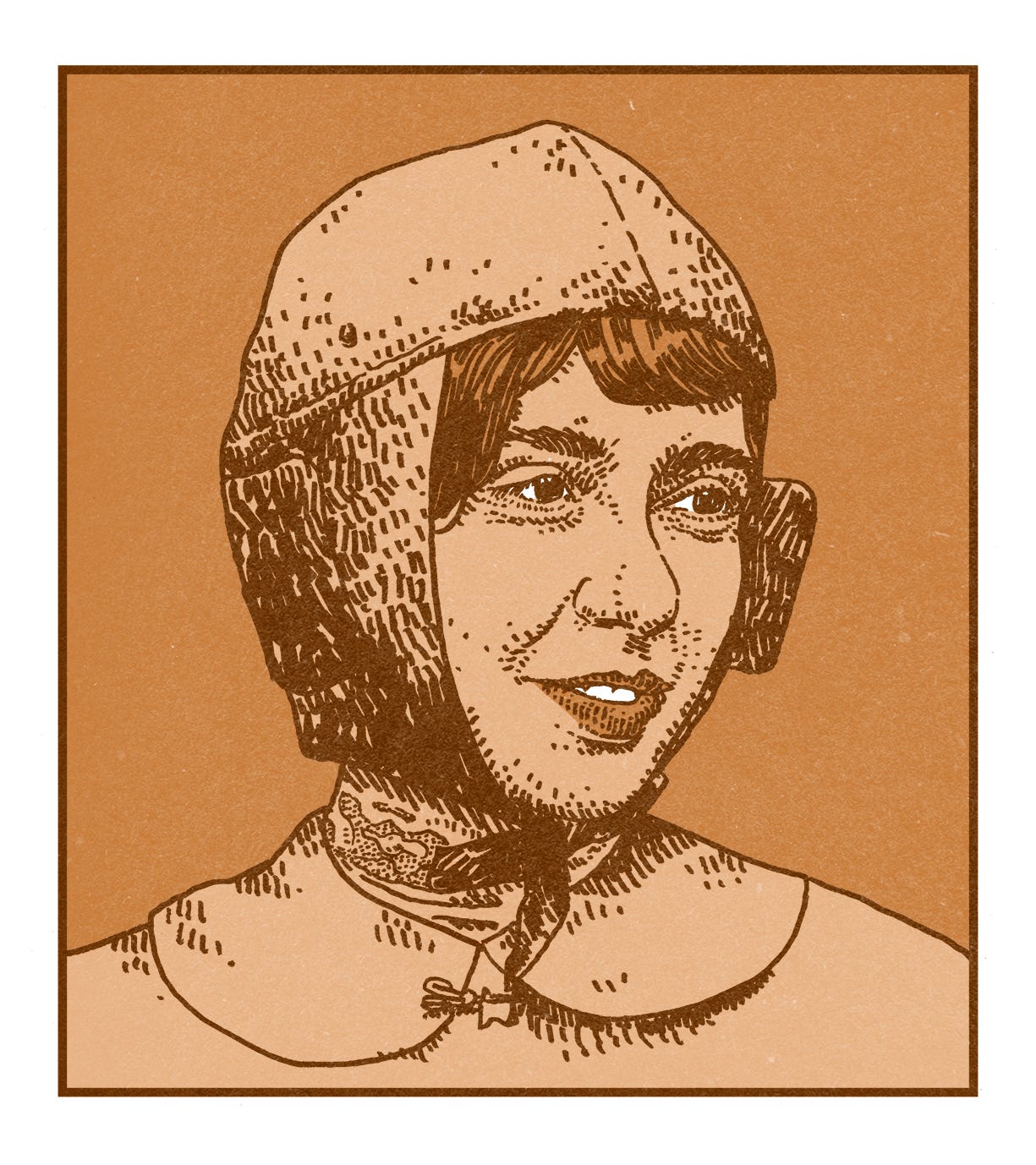

Helene Dutrieu was a world record cyclist, stunt woman, actress—and finally a pioneering aviator.

Welcome to Sports Stories! We write and draw a newsletter at the intersection of sports+history every week. If you’re not already a subscriber, please sign up here—it’s free!

This newsletter is essentially a running conversation between Adam and I. The stories we publish are the result of our varied obsessions and our odd passing interests. We pinball around between different sports and regions and time periods each week, because, well, that’s just how the conversation flows.

But lately Adam and I have landed in one particular place: the lives and stories of early women aviators. So we’ve decided to try something different. For the month of March—which also happens to be Women’s History Month—Sports Stories is going to be a publication about the early days of aviation, a time when simply strapping into an airplane was a feat of courage, and air races, trick pilots, and celebrity aviators were fixed in the world’s collective imagination.

Each week, we’ll share the story of a different pilot. Hopefully, over the course of the next five weeks, these stories will add up to tell a bigger, more complete story; hopefully they will add up to something meaningful.

One of the first things you notice when you start to read about early aviation is just how small the club of aviators was. It was mostly a few eccentrics and oddballs in the United States and France. Kooks with big imaginations. Daredevils wide open to the possibility of falling out of the sky to their inevitable end. Tinkerers who could see possibility where others saw only fear, failure and fiery death.

In 1899, an Ohio bicycle mechanic named Wilbur Wright wrote a letter to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington seeking resources and publications from the collection that might aid him and his brother Orville in their quest to build a working airplane. Here’s how he introduced himself:

“I am an enthusiast, but not a crank in the sense that I have some pet theories as to the proper construction of a flying machine. I wish to avail myself of all that is already known and then if possible add my mite to help on the future worker who will attain final success.”

Four years later, the Wright brothers made their first successful flights at Kitty Hawk. And It turned out that even if Wilbur and Orville were cranks, well, they weren’t alone. Helene Dutrieu was born in Belgium in 1877, and grew up in France. Like the Wright brothers, she was into bicycles. It turns out that bikes can be a gateway drug.

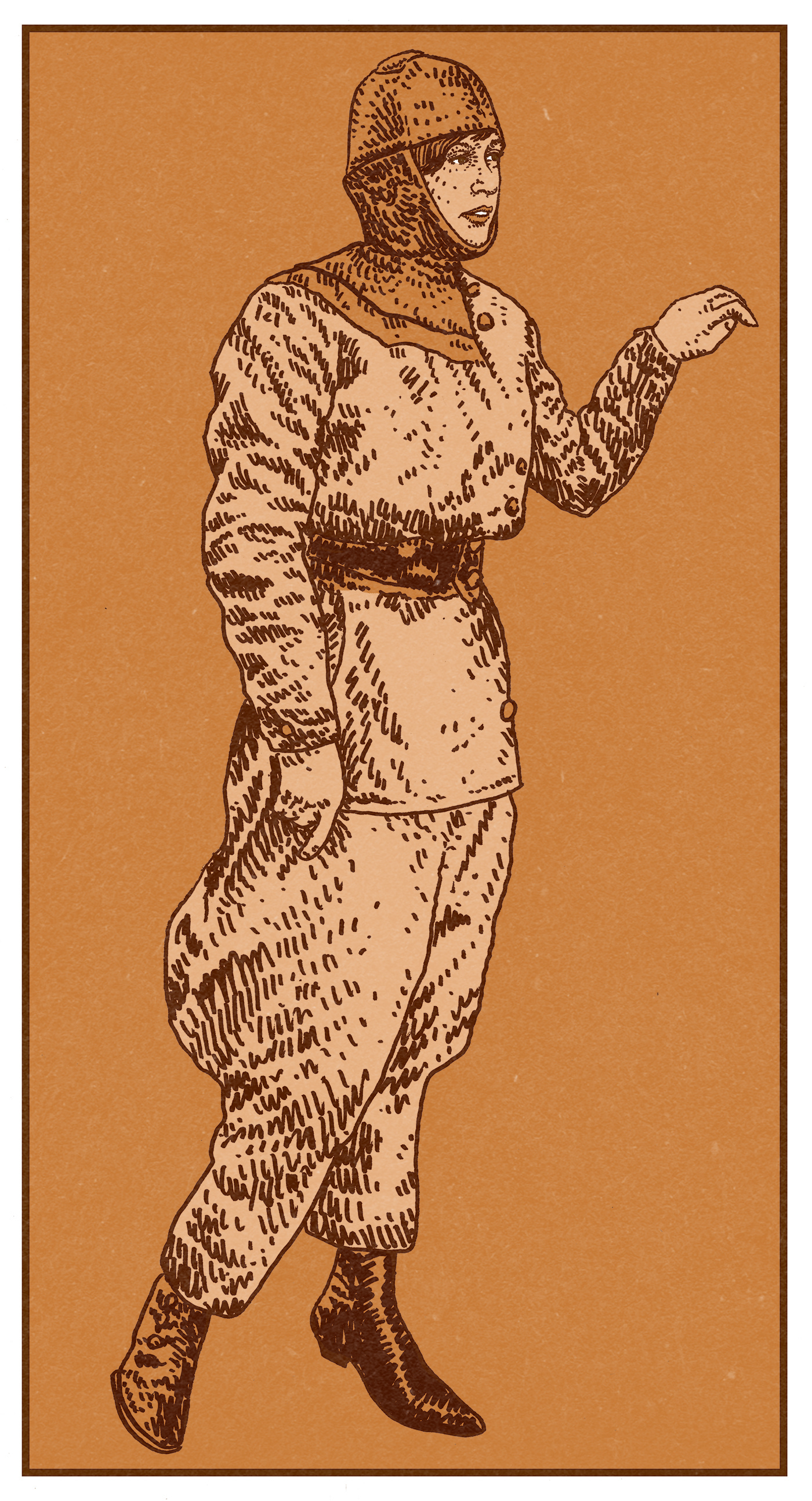

Helene Dutrieu become famous multiple times before she became a world renowned pilot. Initially, it was as a cyclist. In 1893, at just sixteen, she set the women’s hour record in a velodrome in her adopted hometown of Lille, France. By the time she reached her twenties, Dutrieu had advanced past mere races: she became a stunt rider, entertaining crowds under the moniker La Flèche Humaine (the Human Arrow), and then—when she switched to motorcycles—La Moto Ailée (the Winged Moto). She also raced cars and performed stunt driving exhibitions. One of her specialties was looping the loop — driving upside down. After a bad crash, Dutrieu abandoned stunt work for the relatively safe terrain of the stage. She became a theater actor, working in Paris until about 1909.

But the theater was too boring, too quiet, too safe for Helene Dutrieu. She was, after all, an athlete and a swashbuckler and a restless person by nature. While Dutrieu was working as an actress, the aviation craze was taking off (pun totally intended) in France. Louis Bleriot constructed the world’s first successful monoplane in 1907. The newspapers were filled with stories about the exploits of pilots like Bleriot. In 1909, the world’s first international air show was held in Reims, France. Already in her thirties, Dutrieu learned to fly. She was one of the world’s first pilots—man or woman. And one of the world’s most fearless.

It should be noted here how dangerous flying an airplane was at the time Dutrieu got her license in 1910. Even now, the concept is kind of preposterous. You strap yourself into a machine and leave the ground. You defy biology and physics and at any second, if something goes wrong, well…

Flying is improbable. It’s unnatural. It’s borderline magic. This is what makes air travel so terrifying for so many people. Even now, more than a century into the experiment. Even now, in the age of computers and safety systems and autopilot. Even now, armed with statistics about how much safer flying is than driving. In my opinion, we will always be justified in freaking out about this miracle.

Those statistics about commercial jets being safer than cars obviously did not exist in 1910. Hell, cars barely existed in 1910. The jet engine was decades away. Merely getting into an airplane when Helene Dutrieu and her colleagues were doing it was an act of either great courage or total nihilism. Possibly both. Once, when asked about the inherent risks of her chosen profession, Dutrieu said this:

“It doesn’t matter if one is not in love, and I am only in love with my Henry Farman.”

Henry Farman was the maker of Dutrieu’s plane.

Dutrieu continuously defied the expectations placed on her as a woman pilot. She flew in races and air shows around the world, surviving multiple harrowing crashes and yet constantly pushing her planes and herself beyond the limits set for her by others: speed, altitude, distance. Once, her male colleagues tried to stop her from making a 28-mile flight because it would have been too arduous. Dutrieu made the flight. Then soon afterward, set a woman’s record by flying 158 continuous miles. She frequently competed against men, and often enough, beat them. She was the first woman to pilot a sea plane.

As a cyclist, Dutrieu was known as The Human Arrow. As a stunt motorcycle rider, she was the Winged Moto. And as a pilot, she became known around the world as the Girl Hawk. There was always an element of novelty, of entertainment, and of burlesque lingering in the background of Dutrieu’s career. Part of it was the fact that she had come from the theater and before that, had worked as a stunt driver and cyclist in carnivals. But most of it was sexism. Like other women pilots, she had to put up with lots of comments on the way she looked, and on the way she dressed. (“Her achievements were all the more spectacular because of her petite and delicate appearance.”) At one point, she raised a slight commotion because she chose to fly without a corset, arguing, quite reasonably, that it constricted her movements. Everything she did was viewed through the prism of her being a woman. Here’s an item from London’s Evening Standard that was reprinted as part of a suffragist pamphlet called Votes for Women in 1911:

In 1913, Dutrieu became the first woman aviator to win France’s highest civilian award, the Legion d’Honneur. According to the New York Times, she was also the only woman to fly against German aircraft in World War I. (Though I haven’t seen this fact published anywhere else.) During the war, she worked as an ambulance driver, a risky job that entailed transporting injured troops from the trenches back to field hospitals. From ambulance driver, she rose in the ranks of the Red Cross to hospital director. This marked the end of Dutrieu’s competitive flying career. She married a newspaper editor and went to work with him, settling in, after all that, to the relatively quiet life of a journalist.

Helene Dutrieu—the Human Arrow, the Flying Moto, the Girl Hawk—did not fear the early death that came for so many of her peers (some of whom we’ll get to in the weeks to come). Nonetheless, she eluded that fate. She spent her final years as an advocate for aviation and passed away in Paris in 1961 at the age of 83.

Related Reading

I found the best source of clearcut info on Dutrieu to be old contemporaneous newspaper stories. The New York Times was especially big on the aviation beat during her era, as lots of big aeronautical expositions were held on Long Island. But as I noted above, I get the sense that a lot of the coverage of Dutrieu and her contemporaries tended toward boosterism and mythmaking, combined with a lot of sexism.

Here’s a nice little video montage featuring some photos of Dutrieu and some clips of a plane that may or may not be hers:

I also loved this very thorough read on Dutrieu’s cycling exploits and hunt for the women’s hour record from The Podium Cafe. In case you missed it, we covered The Hour Record last year in the context of another great Belgian cyclist, the legendary Eddy Merckx

Thanks for reading Sports Stories. Don’t forget to visit our store for shirts, hats, and cool postcards. Don’t forget to share this post with friends+family. And don’t forget to consider becoming a paid subscriber.

We’ll see you next week.