The Impossible Heights of Lynn Hill

In 1993, Hill became the first person to free climb The Nose at Yosemite's El Capitan. It was a long journey just to the bottom.

Dear Sports Stories Pals,

Some quick updates before we get into this week’s subject:

Thank you to those of you who have signed up for paid subscriptions so far! We got our first batch of Sports Stories postcards in from the printer last week, and we love them so much that we’ve decided to send an entire set to our first 100 paid subscribers. You can sign up starting at $5/month. As always, the actual Sports Stories will remain free to everyone.

We have another favor to ask that is not financial in nature. As you read this week’s newsletter, please think of a person in your life who might enjoy Sports Stories. Then, when you get to the end, forward this email or a link to that person. We’re a small community but we’d like to keep growing -- and the best way to do that is person to person.

Eric & Adam

One of the pleasures of writing Sports Stories is that every week, it gives me a chance to reflect for a few minutes (or much longer) on what exactly sports are and what exactly they are for. It’s a question I keep thinking I’ll get tired of, but I never do. I’m a sucker for the existential stuff.

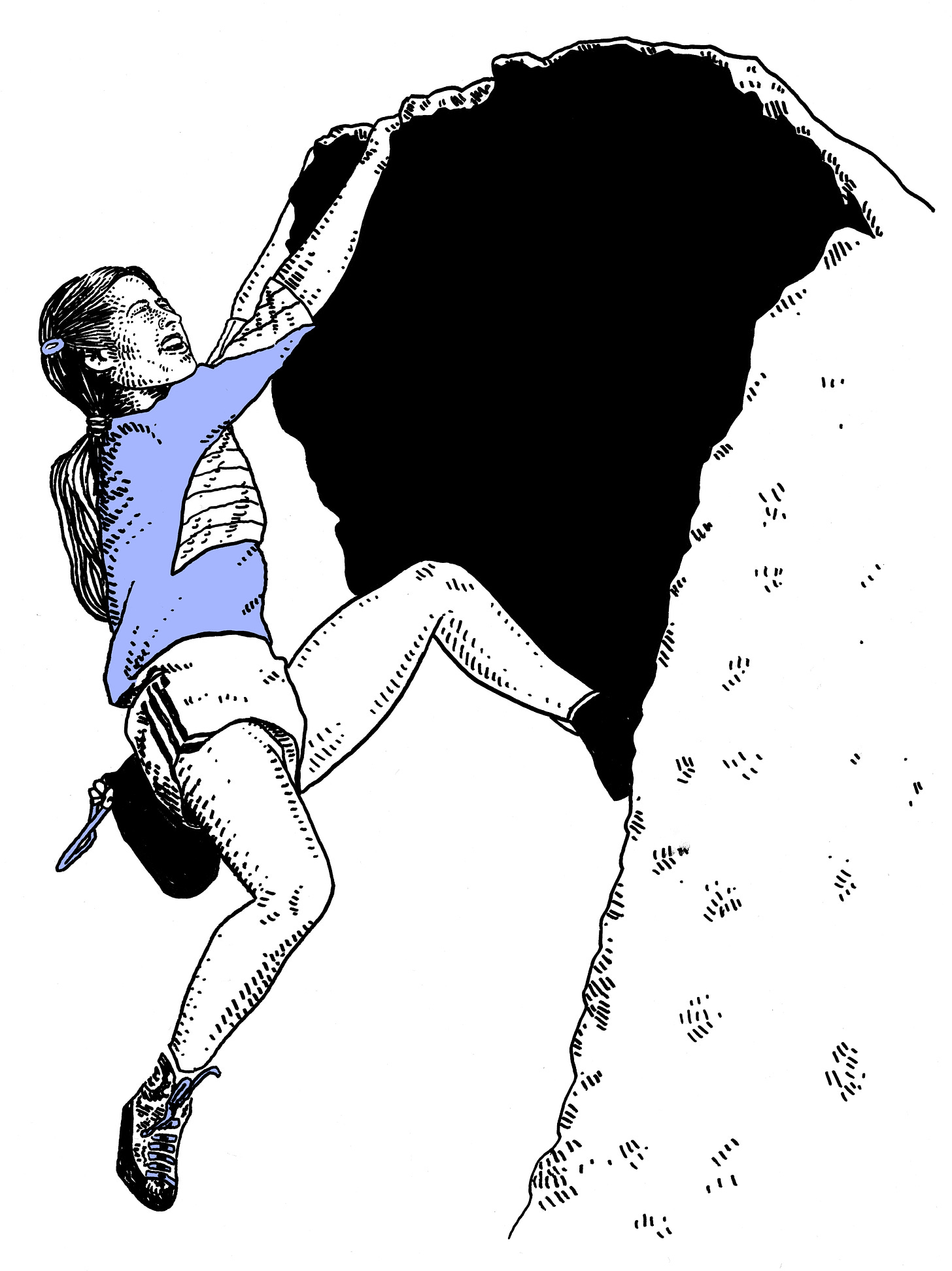

And there’s nothing more existential than standing at the bottom of a cliff, staring up at it, and then beginning to just climb. It’s primal and it’s urgent and the reward -- the victory -- is built into the activity itself. There is no space between the literal and the metaphorical here. You reach the top. You make it. Then you find an even bigger boulder or cliff or mountainside and you start again. It’s a compulsion that is with us from the very beginning. I see it in my kids at the playground.

But obviously for some people, the need to climb stuff is more than just a small part of the human condition. For some people, climbing is the human condition. It’s not just a lifestyle, but a principle around which a life is constructed. Lynn Hill is one of those people. As a girl, she was always climbing. Then saw the stark granite walls of El Capitan at Yosemite National Park on a family camping trip. They site was affixed in her mind from then on.

In 1993, Hill became the first person to free climb El Capitan’s most famous and perilous ascent: The Nose. Without getting too deep into climbing folklore, free climbing The Nose was a holy grail for climbers for decades. Hill’s achievement was a monumental moment in the sport.

And to clarify some language: free climbing is climbing without the aid of tools and devices to help pull yourself up but, with some basic safety precautions like a harness to prevent you from falling to your death. It’s not the same thing as free solo climbing, which is essentially free climbing without a rope.

This is not to say that free climbing is a risk free activity. Before she free’d the Nose, Lynn Hill had experienced some of those risks. Yosemite was where she came up as a climber. After high school, she lived a kind of hobo climber lifestyle in and around the park: camping out and collecting aluminum cans to trade in for cash she could use to buy gear; eating the leftovers from tourists in the park’s cafeterias, sleeping in the dirt without a permit.

“This gipsylike lifestyle was all for a purpose: to climb for as long as possible on as little money as possible. By 1980 I felt an urge to climb that was insistent and compelling.”

That sentence is from Hill’s memoir, Climbing Free. It’s a lovely, winding, and remarkably intimate book. But to me the most personal and vulnerable parts are not when Hill is writing about her interior life, or even her climbing adventures. The most personal writing in the book is about nature. El Capitan is not just an obstacle to climb. It’s a “towering cliff where swallows and peregrines swooped.”

There is obviously an inherent intimacy between a climber and the cliffs they take on. A climber must learn to appreciate even the smallest details of the rock, find the narrowest holds, feel the wind as it plays in the mountains around them. Here’s Hill writing about her first time climbing inthe Shawangunk Mountains, a formation in New York State, more affectionately known as the Gunks:

“The Gunks had their geologic origins four hundred million years ago when ancient sands had been buried, squeezed, and heated into a layer of glasslike quartzite. After the quartzite had emerged from under the earth, erosion and weathering had shaped the outcrops into forms with layers of horizontal cracks and ledges that climbers found perfect for swarming over.”

There is something beautiful and humbling about the fact that even a climber as magnificent and singular as Lynn Hill is really just a speck compared to the rocks that she is conquering -- and nobody is more aware of that fact than her. I get a fraction of this feeling when I look to the southeast on a sunny day in Tacoma and see Mount Rainier standing over the world. But of course, I have never free climbed a 3,000 foot rock wall.

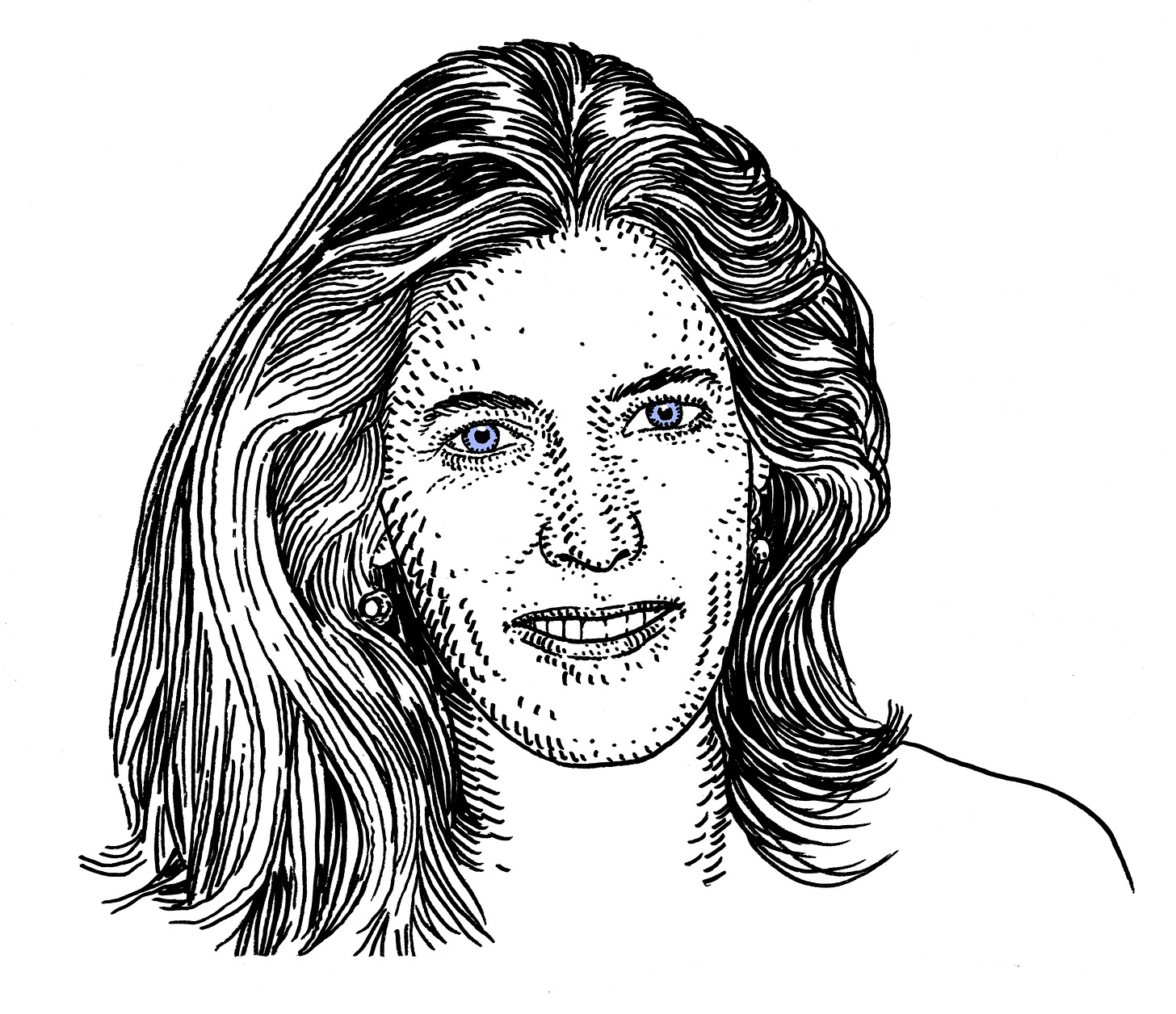

Hill spent the 1980s climbing around the world. She won a ton of speed competitions and even appeared on Letterman in 1989 -- graciously putting up with a lot of leering from the host. Watching the clip, you see an athlete who is funny, self-possessed, and obviously extremely comfortable in her skin:

Blonde and petite, Hill was not necessarily what a person might expect when they think “best rock climber in the world.” But that’s what she was. In his foreword to Hill’s autobiography, the climber and writer John Long notes that Hill faced additional challenges on two levels: geological (“many climbs favor masculine dimensions, such as wide fist cracks and steep faces obliging a long reach”) and societal (“the bone-deep chauvinism most of us had unconsciously embraced soon melted away like fat off a holiday ham.”)

Soon after the Letterman appearance, Hill was free climbing in the cliffs of Buoux, France when she fell. Buoux was a quiet and quaint village. Hill and her then husband Russ Raffa were just outside of town that day seeking to start their morning at a cliff known as the Styx Wall -- yes, named after the river that separated earth from the underworld of Ancient Greece. Despite the name, it was not an especially challenging climb for Hill.

She and Russ geared up, and he ascended first -- clipping their climbing rope to a bolt every so often so that if he fell, he could be held safely by his harness and the attentive partner belaying him on the ground, in this case Hill. But Russ didn’t need her help. He climbed easily to the top before Hill lowered him down the 72 feet back to earth. It was her turn.

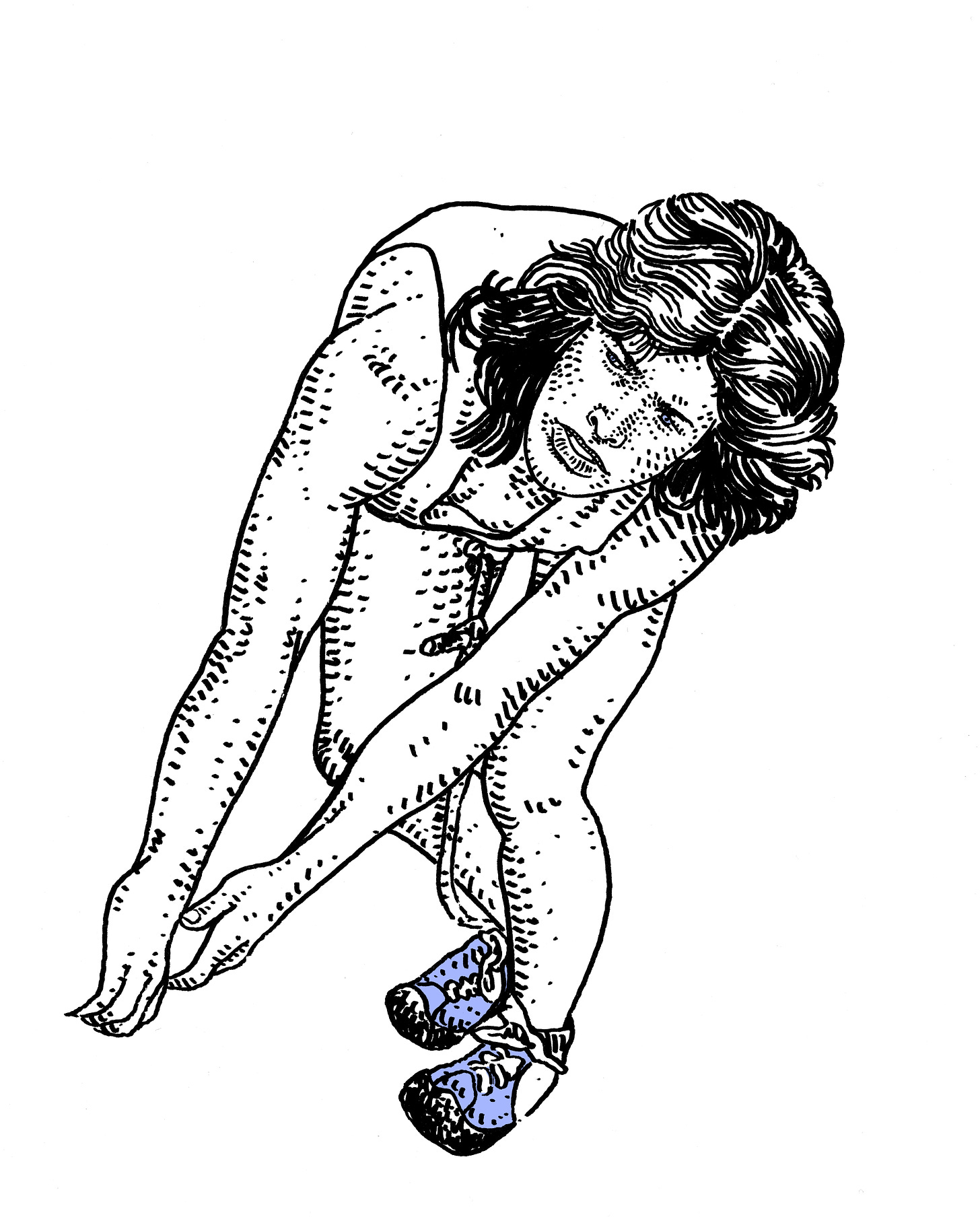

Hill chatted with a nearby tourist. She began to feed the rope through the harness at her waist. She thought about an upcoming competition. She put on her rock climbing shoes. This was just a warmup climb. She didn’t even take off her jacket. But amidst the revelry, she forgot to tie off the rope in her harness. And because of the jacket, she never noticed that it was left there, futile, held in place only by friction.

When Russ was ready, Hill began her climb. “At any point, the rope could have slipped out of my harness and snaked down the cliff through the carabiners to land in a pile on the ground,” she wrote. It would have been fine. Hill could make the climb safely without it. In fact, she did. But when she reached the top, and it was time to belay back down, Hill pushed off the cliff oblivious to her own error, with nothing to hold her up.

She screamed as she fell, down through the air and down through the branches of an oak tree and down into the hard dirt below. Her body, balled up in defiance of the inevitable, bounced three feet in the air before settling on the ground, motionless. But somehow, Hill awoke. She was airlifted to a hospital in Marseilles. She survived, she recovered, and pretty soon she was climbing again.

Six months after the fall, Hill won the Climbing World Cup. Four years after the fall, she was back at Yosemite where it all began, setting out to ascend The Nose. While Hill had won every climbing competition there was, the competitions themselves felt antithetical to her vision of the sport: they were all artifice and ego. You don’t fall 72 feet off a cliff and then get back up only for the external plaudits and indoor climbing courses.

“Climbing is a moving meditation that’s good for my soul,” Hill wrote later on. “It’s my medicine. If I don’t climb, I don’t feel good. I suppose I could replace climbing with some other activity, but climbing is the thing that’s brought me closest to what I would call my natural state of being, closest to a connection with what is.”

It’s corny to write this, but we’re all looking for that connection with what is. For me, writing this stuff is a part of finding it. For Adam, drawing is. But how far would we go? I don’t know the answer to that question. What I do know is that while I’ve never experienced the level of respect and intimacy between a climber and the cliffs they scale, I think I can appreciate it. I think we can all find that connection somewhere.

Here’s Lynn Hill in her own words, one more time, the moment before she takes on The Great Roof, the most challenging feature of her free climb up El Capitan:

While resting at the belay, I looked across the valley at the face of Middle Cathedral. On its mottled wall I noticed a play of shadows form the shape of a heart. I have always noticed the symbols around me, and this heart on stone reminded me of the values that have always been most important in my life and in climbing. My own development as a climber has been an extension of the experiences, passion, and vision of others. For me, free climbing the Great Roof was an opportunity to demonstrate the power of having an open mind and spirit. Though I realized that I could easily fall in my exhausted state, I felt a sense of liberation and strength knowing that this was an effort worth trying with all my heart. I had a strong feeling that this ascent was a part of my destiny and that somehow I could tap into that mysterious source of energy to literally rise to the occasion. I said nothing to Simon of my private thoughts, and when I returned to the roof, I realized that this was the moment of truth.

That initial climb took Hill four days. The next year, she went back and did it again in 23 hours.

Related Reading

As (almost) always, start with the book. Hill’s memoir, co-written with Greg Child, taught me a lot about climbing both from a practical and a spiritual perspective. It also has some truly wild stories in it. You can pick it up here.

Hill remains active in the climbing world. She coaches, speaks, and consults among other things. She has a website full of info on what she’s up to that also features some insightful passages she has written, interviews she’s been a part of, and more. Plus, her YouTube channel is full of incredible archival footage.

One other cool thing: Hill was part of a pretty awesome interactive special project with Google Maps where she and two other legendary climbers, Alex Honnold (of Free Solo fame) and Tommy Caldwell, guided readers up El Capitan. You can get lost in it here.

Finally, in Hill’s book Climbing Free, she offhandedly mentions that a private plane full of weed crashed at Yosemite in 1979, the year before she moved there. She talks about climbers who had been vagabonds like her suddenly emerging with vans and full stomachs. It didn’t seem real, but this actually happened. Here’s a really fun 2016 story on it from Men’s Journal .

Thanks again for reading Sports Stories. We hope your holidays are full of good health, good cheer, and good vibes. See you next week.