The Long Flight Home

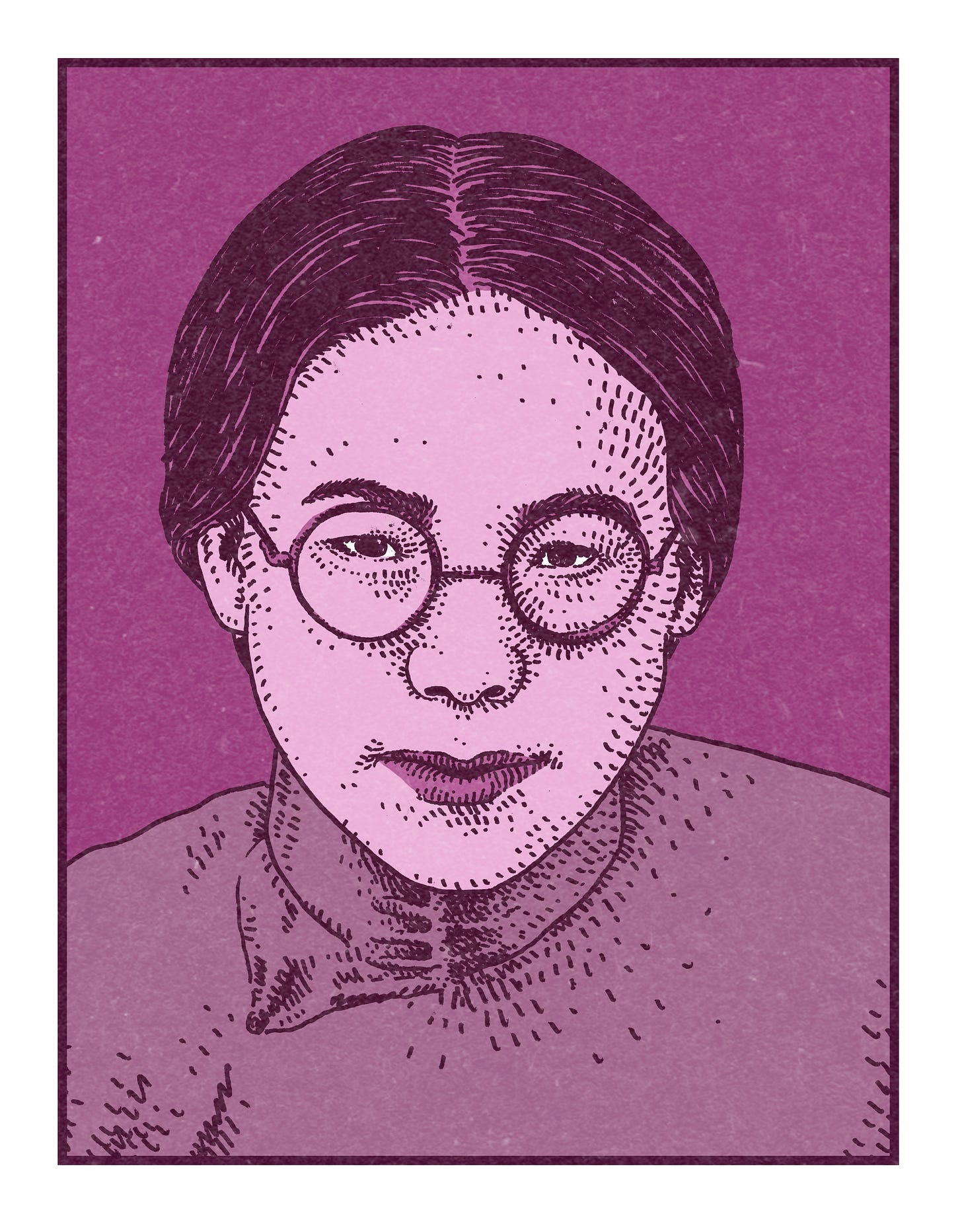

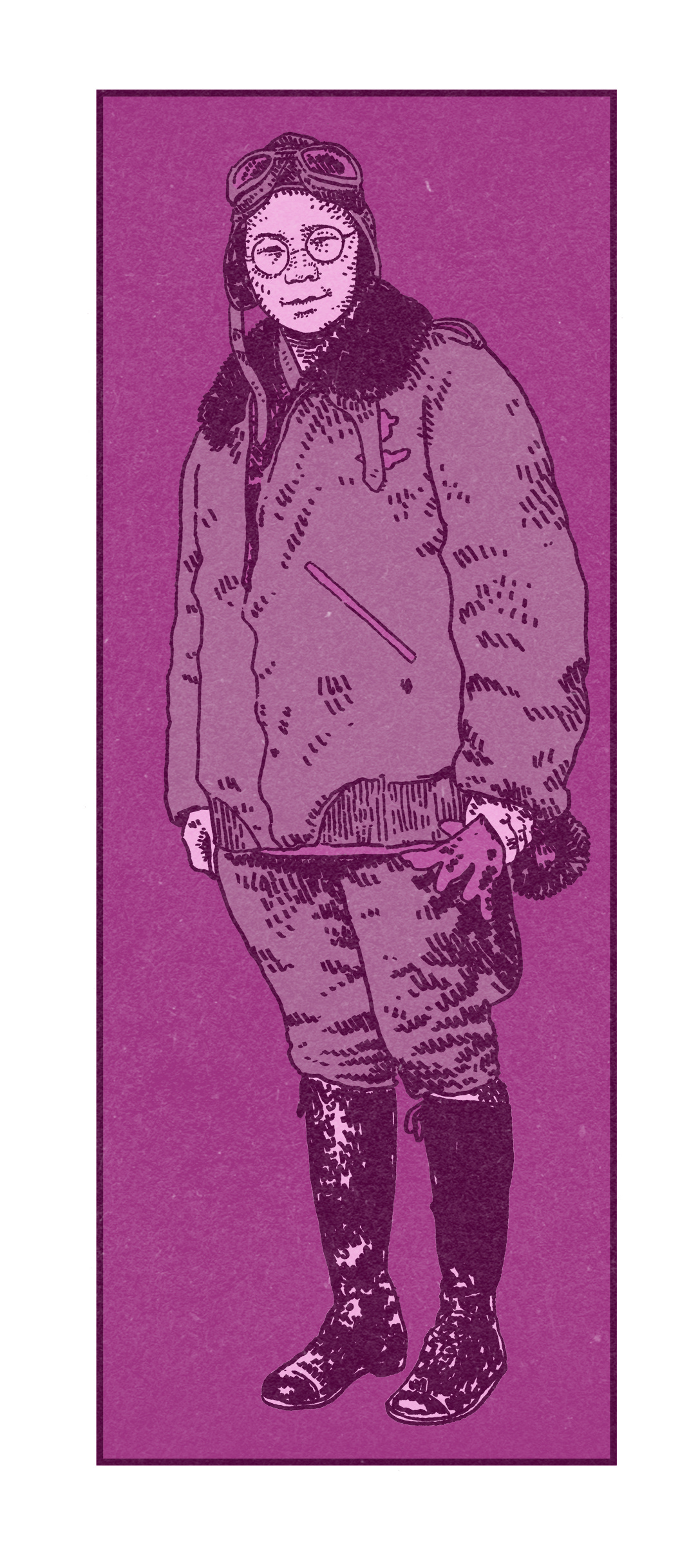

Kwon Ki-Ok's career as a barrier-breaking pilot was wrapped up in her revolutionary activism for an independent Korea.

Welcome to Sports Stories, a publication at the intersection of sports and history: written by Eric Nusbaum, illustrated by Adam Villacin, and delivered to your inbox every Tuesday. This month we’re covering early women in the history of aviation. If you’re not already a subscriber, please sign up here—it’s free!

It’s hard to overstate just how much guts it took for early women aviators to even declare that they wanted to learn to fly an airplane — even before they got in the air. The concept of powered flight was nascent, the technology unreliable. And women’s rights activists were still fighting for the most basic recognition, still fighting for suffrage. Even the act of simply saying “I am going to be a pilot,” was a political one. In addition to sharing a sense of wanderlust— and a fearlessness and imagination that few people on earth in those days possessed—the early women pilots were activists whether they identified as such or not.

Some pilots, like Helene Dutrieu and Matilde Moisant, didn’t explicitly bring politics into their public personas. Others, like Bessie Coleman, viewed flying as being part of a civil rights mission larger than themselves. Like Bessie Coleman, Kwon Ki-Ok’s career as a pilot was wrapped up with her political beliefs; it was wrapped up with global events that tossed and turned her life for decades.

The details available in English are a little bit fuzzy, but the story is remarkable. Kwon was born in Korea in 1901 to a wealthy family living in the outskirts of Pyongyang. In the early years after Kwon’s birth, Japan exerted increasing amounts of control over Korean society before finally annexing the Korean peninsula in 1910.

These events had a profound impact on Kwon. For one thing, her family lost its money. For another, the Japanese rule would come to define her existence in the same way it did for everyone in occupied Korea. Everything simply changed.

Kwon’s other preoccupation, of course, would be flight. When she was a teenager, an American stunt pilot named Art Smith barnstormed through Korea and Japan. Kwon, then a high school student, was captivated.

(Smith’s demonstration was also seen at another stop by a Japanese teenager who became fascinated by the ingenuity and mechanics of flight. He began to tinker with motors himself, and would eventually make a career out of that tinkering. His name was Soichiro Honda.)

But it wasn’t as if Kwon, a sixteen year old in occupied Korea with few resources, could simply go enroll in flight school. Plus there were other more pressing matters. As a university student in the years to come, she would become deeply involved in the March 1st Movement, a burgeoning protest calling for Korean independence from Japan. She raised money, she sewed Korean flags, and she got herself thrown into jail two separate times.

After her second stint behind bars, Kwon was forced to leave Korea. It was 1921. She traveled on a fishing boat to China, where she settled in the city of Hangzhou, learning Mandarin and English and eventually returning to her dream of aviation. In 1925, Kwon enrolled in the Republic of China’s Air Force Academy. She was the first woman to graduate from the academy and become a pilot in the Chinese Air Force, and is widely considered to be the first Korean woman to become a licensed pilot.

Kwon rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Republic of China Air Force, but she never stopped dreaming about returning to an independent Korea. While she was in China, she managed to escape an assassination attempt by the Japanese government. According to some stories, Kwon dreamed in particular of flying in battle against Japan—doing her part to liberate her homeland. She was actively involved in the Korean Provisional Government, which, in addition to its more official government-in-exile activities, coordinated armed attacks on Japanese government officials in Korea. Kwon reportedly tried to get money together to acquire planes that the provisional government could use to bombard the Japanese occupiers—but planes with the necessary range were impossible to come by.

Kwon never got the chance to fight Japan in the air. But after the liberation of the Korean Peninsula in 1945, she was finally able to go home. Kwon moved to Seoul where she helped establish what would become the South Korean Air Force, and went to work in the country’s defense ministry.

Kwon Ki-Ok had left Korea in a fishing boat, fleeing for her life. She returned as an officer, a revolutionary leader, and a barrier-breaking pilot. It may not have been the journey she anticipated when she first saw Art Smith doing barrel rolls in the sky as a teenager, but it was all hers.

Etc.

Some of our paid subscribers have written to share that their postcard sets have arrived at addresses across the country. We’re stoked to hear that.

Remember, if you want some of Adam’s beautiful postcards, you too can become a paid subscriber. We really appreciate all your support.

And if you *already are* a paid subscriber but have not filled out this form, please do it. We need your contact info if we’re going to send you cool stuff.

Related Reading

There isn’t a ton of detailed material in English on Kwon Ki-Ok — at least not readily available. I thought the most complete story on her life was this one from a group called the Voluntary Agency Network of Korea. However, considering the details of Kwon’s life, it is worth noting that the Wikipedia for VANK includes a section about how have been criticized for being anti-Japanese. (One of their causes is trying to get folks to use the phrase “East Sea” instead of “Sea of Japan.”)

This story from KBS World also had some great detail on her time in China.

Kwon is also featured as an entry in Justin Corfield’s Historical Dictionary of Pyongyang.

Blue Swallow

As I was researching Kwon, I came across a Korean film called Blue Swallow that was released in 2005. From what I have read, Blue Swallow is a very well-made drama about a pioneering woman aviator named Park Kyung-Won set in the 1920s. It was also an absolute box office disaster, mired in controversy. The studio behind the film advertised its protagonist as the first Korean woman pilot (erasing Kwon Ki-Ok) and the film itself was accused of having an underlying pro-Japanese sentiment. I haven’t seen it, and I don’t claim to have enough understanding of the historical background to opine, even if I had.

Thanks for reading Sports Stories. We’ll see you next week.