Welcome to Sports Stories, a newsletter written by Eric Nusbaum, and illustrated by Adam Villacin. Every week, we’ll be learning about sports, history, and sports history. We hope you enjoy Sports Stories — and that if you do, you share it with your friends, families, and any funeral home directors you might know.

As you may know, today is Halloween. In honor of the holiday, I wanted to come up with a Sports Story that would be appropriately creepy and terrifying. (I should have probably held onto The Klansman for this.) Somehow, between getting ready for Halloween and watching the World Series on TV, my mind wandered instead to an old-time baseball player who I knew more for his cool name and cool nickname than for anything else. His cool name was Waite Charles Hoyt. His cool nickname was The Merry Mortician.

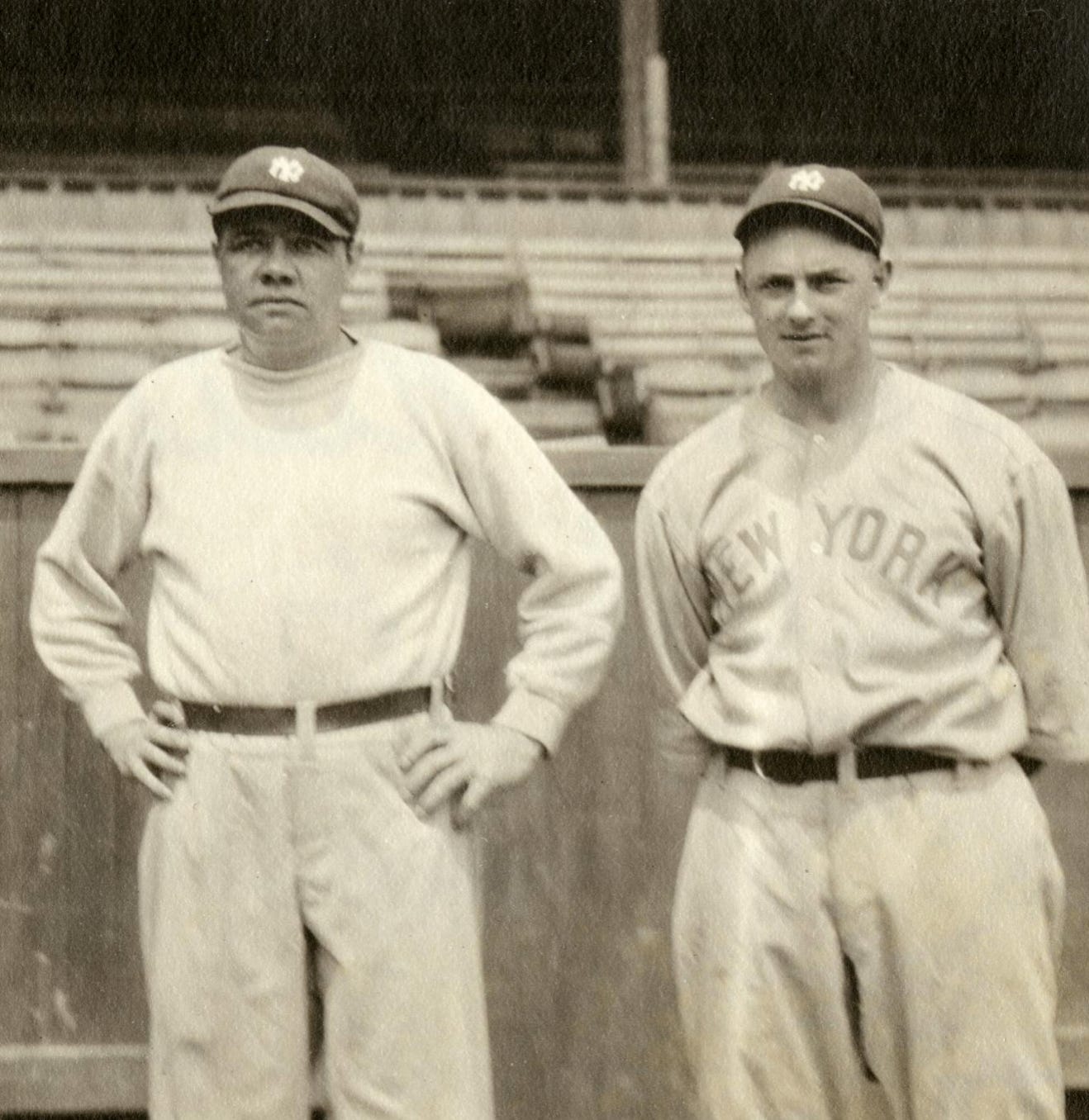

It turns out that Waite Hoyt was even more interesting than his nickname implied. First of all, he wasn’t some regular, unremarkable journeyman, some ancient version of Andy Ashby or Jason Vargas. He’s in the Hall of Fame. He was the best pitcher on those glorious 1920s Yankees teams. He was also Babe Ruth’s best drinking buddy. And for as big and thirsty and righteously animalistic as the Babe was, well, Waite Hoyt was the opposite. He was a sophisticated man. He was a ballplayer, but he could have been many other things. He was a ballplayer, and he was many other things, including, yes, a mortician.

Hoyt was born in Brooklyn to a writer mother and a vaudevillian father. His birthday was September 9, 1899: 9-9-99. This was always significant to him. It added to his sense of his own legacy. Waite Hoyt was the kind of kid who was good at everything, and knew it. He even had a delightful singing voice. But it didn’t always go easy for him. Hoyt was signed at just fifteen years old by John McGraw, manager of the New York Giants. Because he signed before he finished high school, sports writers called him “Schoolboy.” He apprenticed under Christy Mathewson, who, in his time, was probably the best pitcher to ever live.

But Hoyt wasn’t destined to be a Christy Mathewson. (Perhaps that’s a good thing; Christy Mathewson enlisted in WWI, served in the chemical unit, and caught a fatal case of tuberculosis from exposure to mustard gas.) Hoyt, meanwhile, struggled in the minors, and quit baseball before he turned twenty. He went to college for a single semester. He played semi-pro ball in Baltimore. Finally, despite himself, he landed with the Boston Red Sox. This was at a time when the Red Sox owner, Harry Frazee, was initiating one of baseball’s first “rebuilds.” (He was broke). Frazee sold Babe Ruth to the Yankees in 1919, and traded Hoyt to New York a year later.

The Yankees were owned by an old money industrialist/soldier/politician named Jacob Ruppert Jr. Everyone called Ruppert The Colonel, which makes him sound like the villain from an old detective novel. One of The Colonel’s principal tendencies was that he was cheap as hell. That meant Waite Hoyt wasn’t making the money he wanted to make playing baseball. He also didn’t have much leverage when it came to salary negotiations. So he did the smart thing: diversified. He appeared regularly in vaudeville acts. He dabbled in pro basketball in the offseason. And he went to work for his father-in-law, who owned a mortuary in Brooklyn.

The tales from Waite Hoyt’s mortuary career make you wonder how he managed such a long career as a ballplayer, or as anything, really. Once, on a sweltering summer day, he supposedly picked up a body in the company hearse before pitching a day game at the Polo Grounds in Harlem. When he realized he wouldn’t have time to get the body out to the mortuary, Hoyt decided to just drive straight to the ballpark. As the body lay in the hearse, and the hearse remained parked in the sunshine, Hoyt threw a shutout. By the time the body reached the mortuary, Hoyt biographer William A. Cooke wrote, “it had started to take on a rather nauseating odor.”

But despite the stories, Hoyt was relatively serious about his work in the funeral business. He did everything except embalm bodies—and he was on the edge of taking that final step, before the baseball gods (spooky baseball spirits? haunted baseball ghosts? ) interceded. One year, the Yankees were prepared to let Hoyte skip a game to take the test to become a journeyman embalmer if they managed to clinch the pennant before the September 28 exam date date. They didn’t. Hoyt never took the exam. He never actually became an embalmer. But to fans, he would still be the Merry Mortician. (Don’t worry, we’ll get to embalmer athletes later on.)

It would be unfair to leave Hoyt right there. In a way, his playing career was only the beginning. Hoyt retired in 1938, and soon became one of the first ex-players to go into broadcasting. He had a long career as an announcer with the Cincinnati Reds. When Babe Ruth died in 1948, Hoyt spent an entire broadcast telling Ruth stories, with no prepared notes. He later wrote a short book about his good friend The Babe, and unsurprisingly that book, “Babe Ruth As I Knew Him,” is both deeply insightful, and incredibly entertaining. Seriously, it’s great. You can read the entire thing online by clicking here.

Hoyt was a person who never stopped learning. He was even a good enough oil painter to show his work at galleries. But if you asked him, Hoyt might have said that the most meaningful thing in his life was his recovery from alcoholism. In 1945, Hoyt famously disappeared for a few days on a terrible bender. His wife at the time cited Hoyt’s disappearance to a case of amnesia. This prompted Hoyt’s old friend Babe Ruth to send him a telegram:

“Read about your case of amnesia. Must be a new brand.”

But instead of making light of his disappearance, Hoyt apologized publicly. He went into Alcoholics Anonymous, and spent the rest of his life advocating for the group, and telling his story to whoever might be interested in hearing it. Hoyt had the kind of life that gave him perspective on just how frivolous baseball was: he was a bookish, relatively privileged kid who could have easily been a success in another field. But he also had the kind of life that led him to realize how lucky he was to have played the sport, to great success, for two decades. Baseball made him happy. He knew what a blessing this was.

It’s hard not to wonder about how Hoyt’s career in the funeral business affected his perspective on the sport he loved. Death is obviously far from the mind of a baseball player in the middle of a game. Ultimately, baseball is a way to fill the time we’re actually alive, it’s a way to distract ourselves, for a few hours, from the fact that that we won’t always be.

But baseball is also a game that is deeply connected to its dead guys. It’s a game with treasured ghosts. It’s a game with a lot of stillness, and a lot of quiet moments to think about those ghosts. Waite Hoyt wasn’t immune to this kind of thinking. It became his job, as a broadcaster, to usher fans through those quiet moments.

Related Reading

If you really want to get into Waite Hoyt, you should read the book on him, by William A. Cooke: Waite Hoyt: A Biography of the Yankees’ Schoolboy Wonder. But otherwise, I’m not sure it’s a necessary read. This is a somewhat dry book on a man whose own memoirs would probably have been neither of those things. Plus, Hoyt’s son commented on the Amazon page saying that the author never bothered to reach out to his surviving family members—not a great sign.

Hoyt’s actual autobiographical writing remains unpublished in the archives at the Cincinnati Historical Library. If anybody wants to send Adam and I out there to turn them into a cool nonfiction graphic novel, we’d be happy to go do that. We’d also interview any and all living Hoyts.

Otherwise, I really enjoyed an excerpt from a never-published book on Hoyt written by a writer named Ellen Frell. This excerpt was published by the Cincinnati Museum, and can be found here. For a fast-living Brooklyn kid and Yankees superstar, Hoyt really embraced Cincinnati, and the city embraced him back.

To me the best way to get to know Waite Hoyt is through listening to him talk. There is some audio on YouTube of his old broadcasts. His rain delay fill-in stories were especially legendary. There’s also this documentary about Hoyt, which is interesting but incomplete.

Dead Guy Guys

Waite Hoyt is not the only pro athlete to have worked in the death industry. In fact, he actually regularly pitched against a fellow mortician: an infielder for the Cleveland Indians and Boston Red Sox named Johnny Hodapp. Hodapp was the son of an undertaker, and worked in the business in offseasons, then after he retired. He came to the plate 50 times against Hoyt, and hit a respectable .298. His family business, the Hodapp Funeral Homes, remains active.

Many years after Waite Hoyt, another Hall of Fame player became a funeral director. Andre Dawson, who played for two decades with the Expos, Cubs, Red Sox, and Marlins, invested in a funeral home after he retired. Then he invested in another one. Then, all of a sudden, he was running it. Dawson and his family own and operate the Paradise Memorial Funeral Home in Miami’s Little Havana. Dawson does it all. A couple years ago, he told the writer Bob Nightengale about going to pick up a body, only to have the son of the deceased recognize him in awe, run to the other room, and retrieve a picture he had taken with Dawson as a child. “We come here, Dawson told Nightengale. We’re gonna have to leave here.”

Before Dawson’s baseball career got going, journeyman outfielder Richie Hebner (an underrated hitter) spent his offseasons digging graves at a Jewish cemetery in Massachusetts, where his grandfather, father, and brother, had all worked as caretakers. Hebner, who earned the nickname “gravedigger,” liked to joke about the job with the press. Here he is in Sports Illustrated:

I got lots of stories. One woman, they forgot to take off her wooden leg, and we had thrown several shovels of dirt on her already when somebody came up and said we had to get her back out so they could get her wooden leg. Another woman fell into the grave in the middle of the service. Did a header. 'Get her out, get her out,' the rabbi was yelling. I said, 'Naw, leave her in there and give her a discount.' The rabbi looked at my father and said, 'Who is this you've got digging graves?'

But the best death-related nickname in pro sports isn’t Hoyt’s “Merry Mortician or Hebner’s “Gravedigger.” (Though Grave Digger does happen to be the name of my favorite monster truck.) The best deathly nickname belonged to a hockey player named Alf Pike: The Embalmer.

Unfortunately, the name actually referenced Pike’s job as a mortician, not what he did to opposing skaters. Pike was actually famously nice, on the ice and off. Plus, he was more of a scoring forward type than a goon. He helped the New York Rangers to the Stanley Cup in 1940, his rookie year, and eventually had a long career as a coach. He lived to be 91 before meeting his own embalmer in 2009.

This has been Vol. 6 of Sports Stories by Eric Nusbaum (words) and Adam Villacin (art). If you have any questions, comments, or concerns, please reply to this email or contact enusbaum@gmail.com. We’d love to hear from you.

Sports Stories is 100 percent free. If you enjoyed this week’s newsletter, and want to show your appreciation, the best way to do that would be to sign up, share it on social media, or forward it to someone you think might enjoy it too.