The Murder of Octavius Catto

The story of Octavius Catto is one you’ve heard before -- even if you haven’t.

The story of Octavius Catto is one you’ve heard before -- even if you haven’t.

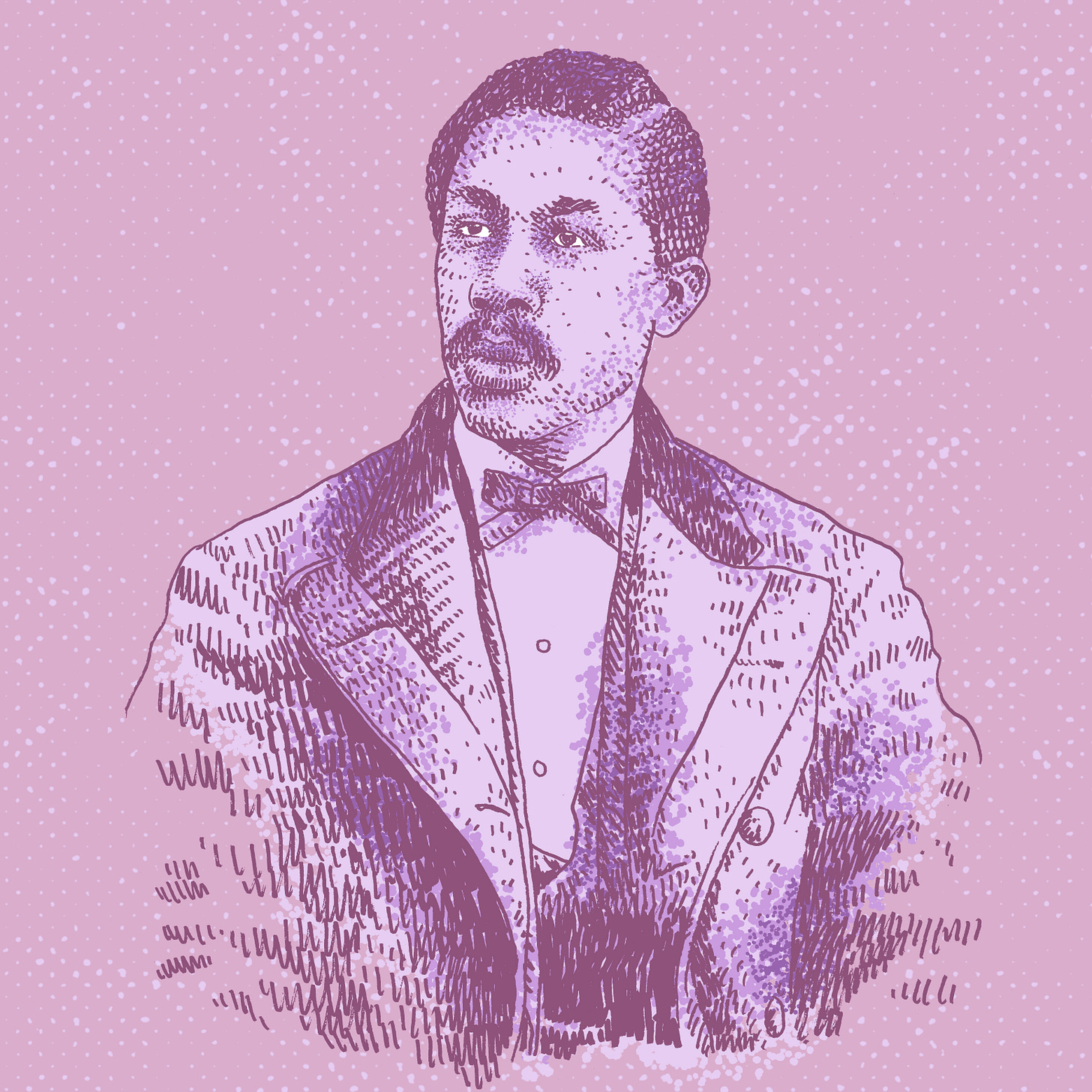

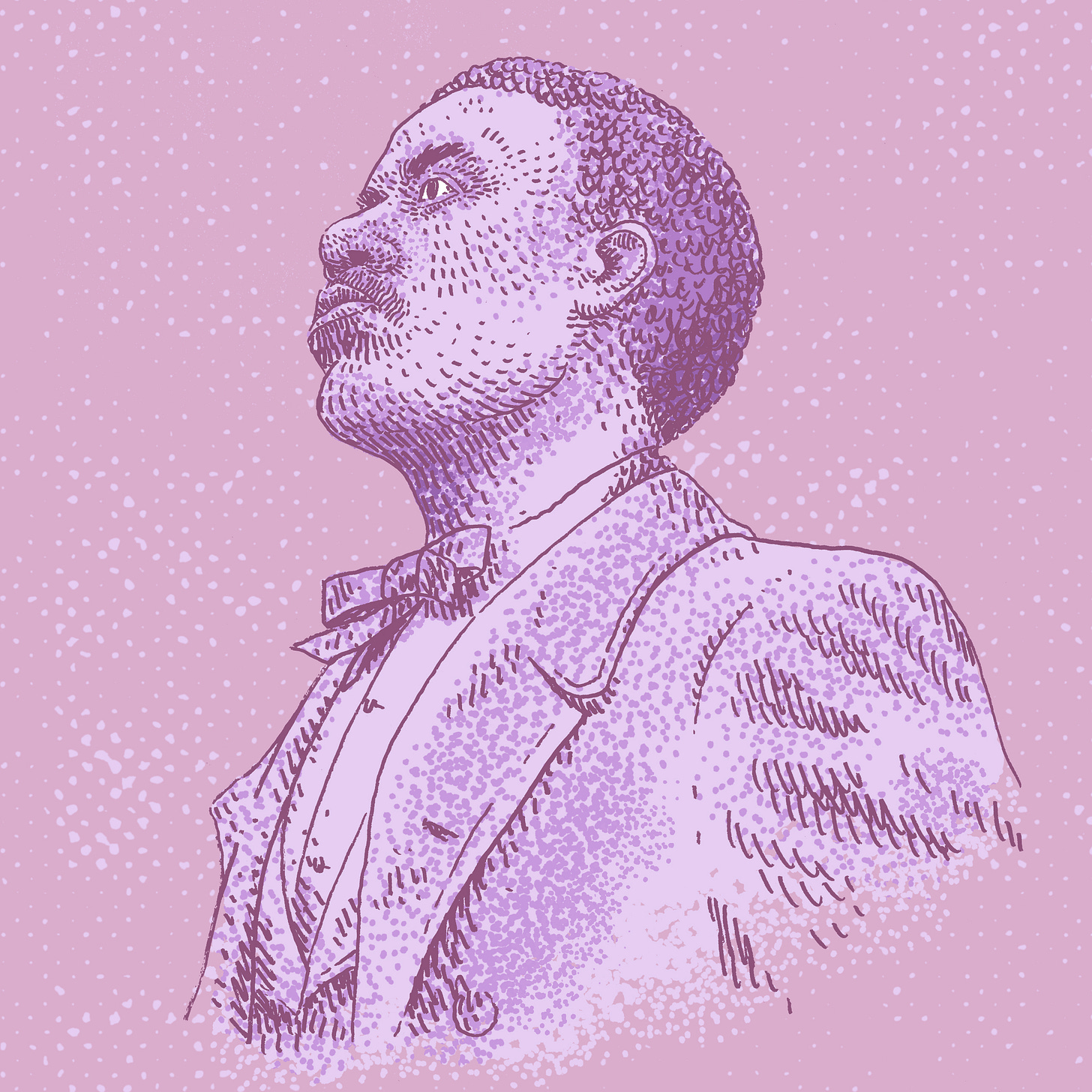

Octavius Valentine Catto was born in South Carolina to free parents in 1839. His father William had purchased his own freedom and become a minister, and the family had plans to sail from Baltimore for Liberia when Octavius was a little boy. But that was scuttled before they could get out of town, because William was accused of attempting to foment a slave insurrection. The family fled north to Philadelphia. This was where Octavius would grow up.

He was a brilliant kid. A prodigy, a genius, all those other golden words. His brilliance extended to the social realm, too. He had many friends. He was a leader. Philadelphia was a harsh and violent and racist place, but the city also had strong black institutions that nurtured Octavius.

The facts of Catto’s life have been recounted over and over. He vocally challenged the racist white teachers at Philadelphia’s only black high school, the Institute for Colored Youth. Then he began to teach there himself. After the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1863, Catto rallied black Philadelphians to enlist in the Union Army, going so far as leading a delegation to the state capital of Harrisburg to sign up -- only to be turned away by Union officers. Catto eventually joined the Pennsylvania National Guard and became an officer.

Catto helped form the National Equal Rights League. He worked alongside Frederick Douglass to help pass the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. Catto even led an early sit-in on a horse-drawn trolley. African Americans were banned from the trolleys in Philadelphia. One day, after years of advocacy, a fed up Catto boarded a trolley and simply refused to leave. Finally, the driver unhitched his horse from the trolley, and galloped away leaving Catto alone inside. This was only the beginning of his fight, but ultimately, the trolleys of Philadelphia were integrated in large part because of the organizing of Octavius Catto.

Amidst all this, Octavius Catto played baseball. In fact, he absolutely loved baseball. He was a second baseman. The sport was in its early days as a Big Thing in American life, and Catto not only liked to play, he was a true believer in the idea that baseball could be a positive force in society. He founded a club that became known as the Pythians (based on the name of a fraternal order to which Catto and some of his teammates belonged, the Knights of Pythias.) The Pythians were the second African American club in Philadelphia after the Excelsiors. But they were very clearly the superior club -- often traveling to other cities like D.C. for games against other teams.

Catto saw baseball as a part of his larger goal. To Catto, the sport was a vehicle for activism. He turned games between all black clubs into more than just games. They were political rallies, social events, and above all, opportunities to organize. Catto would pair his ballgames with speeches and potluck dinners.

In 1867, Catto applied for his club to be admitted in the local chapter of the National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP). This was an era before formal leagues had really taken off, and before professionalization changed the sport forever. The NABBP was the closest thing there was to an organizing body for baseball. Catto’s Pythians even had the support of Philadelphia’s greatest white baseball club, the Athletics. But the Pennsylvania chapter denied the Pythians membership.

Catto appealed to the national convention of the NABBP. He was once again rejected. That rejection became the first formal enactment of a color line in organized baseball. And in its wording, we can recognize a very familiar kind of racism:

“If colored clubs were admitted there would be, in all probability, some division of feeling, whereas by excluding them no injury would result to anyone.”

Essentially, the members of the NABBP did not want to be forced to confront their own racism. They wanted to stick to sports. They literally banned black athletes so they would not have to make white athletes uncomfortable. It was 1867, but it might as well have been 2017. In their vote, and their explanation for it, the NABBP also neatly rejected the humanity of Catto, his team, and every other African American ballplayer.

Look at these words again: “Whereas by excluding them, no injury would result to anyone.”

Ahh yes, no injury would result to anyone. Can’t think of anyone at all who would be injured by this decision.

The NABBP ruling is an unfortunately perfect example of how swiftly and easily institutions and the individuals who run those institutions can apply their power to dehumanize people, and even erase them. It’s a crime that is deep and unforgivable and a crime that continues to be repeated again and again and again.

Octavius Catto did not take well to erasure or denial. He sought out white clubs to take on his Pythians, even without the approval of the racist NABBP. Some clubs seemed on the verge of accepting the challenge, but nobody would actually step up -- not even the Pythians’ supposed allies, the Athletics, with whom they shared a stadium. Finally, in 1869, Catto led his Pythians in a game against an all-white team, the Olympic Club in front of an integrated crowd. Here’s Robert Elias setting the scene in his SABR bio of Catto:

“The Pythians took an early lead but their star pitcher, John Cannon, was injured, and couldn’t give his best game. Back then, with only one umpire on the field, it was left to the players themselves to call safes and outs. The umpire was limited to hearing appeals when a team thought there was a bad call. The Pythians decided beforehand not to argue any plans. Any appeals would amount to a black man challenging a white man’s word in front of 5,000 people.”

The Pythians lost 44-23, but sympathetic newspapers reported on the bad calls they faced. The following month, the Pythians took on another white team, the City Item Club, and won 27-17.

Another thing Elias noted: the members of the Olympic Club, the Pythians’ first white opponents, were “hardcore Democrats.” This was a big deal. There was no small amount of tension between the Irish and the African American community in Philadelphia. They lived close to one another. They had different politics, too. The Irish were Democrats. The black community was aligned with the Republican party -- and that was about to really matter.

In 1870, the 15th Amendment was finally ratified. This was one of Catto’s great achievements. The vote meant everything to him. If baseball was a way of belonging in American society; of expressing American values; of competing on a level playing field with white men, then voting...voting was even bigger. Octavius Catto had been born for this. He had used all his gifts and fought like hell to help make it happen.

The right to vote had been restricted to white men in Pennsylvania dating back to a law passed before Catto was even born. And Catto understood that even with the law on his side, actually organizing a fair vote would not be easy. The scholar Jerald Casway wrote that by 1870, Catto became so consumed with the vote that he let the Pythians slide into a state of suspended animation. They played fewer games, stopped recruiting new players, and slowly became an afterthought. Here’s Casway:

“Organizing and coordinating the black vote took precedence over everything. Catto anticipated that the black electorate would be challenged by the Democratic leadership of Philadelphia. In the past the all-white police force had tolerated violence by fire and hose companies composed largely of Irish immigrants against the city’s blacks.”

Philadelphia’s mayoral election was scheduled for October 10, 1871. What actually happened in the days leading up to that election and on the fateful day itself is not completely clear. Nothing from 150 years ago can be. But the big book on Catto is called “Tasting Freedom” by Daniel Biddle and Murray Dubin. They did a painstaking job researching Catto’s entire life, including this election day.

White police officers across the city were physically attacking black voters, and encouraging white Democrats to do the same. People were dying. Concerned about their safety, Catto dismissed his students from class early that day. Biddle and Dubin describe officers literally beating up black voters in line for the polls, yanking them away, and replacing them with white voters. They describe officers beating black voters indiscriminately. The election devolved into a full blown riot. There were accusations of fraud, and there was violence, violence, and more violence.

Amidst the chaos, the National Guard was called in -- of which Catto was still an officer. His duty as such required him to wear a dress blue uniform, a sword, and a sidearm. Catto didn’t own a gun, so he went to a pawn shop and purchased a revolver. Accounts differ as to where Catto went next. Perhaps he was on his way to vote. Perhaps he was just going home before reporting for duty with the Guard. At home he had his uniform, his sword, and his bullets.

Catto was walking down South Street when a white man passed him, paused, crouched, and pulled a gun. As Catto retreated with his hands out, the white man fired. The shot knocked Catto back but did not kill him. “What are you doing?” Catto apparently gasped, hugging his wound. But the man approached, following Catto as he tried to take cover behind a streetcar, coming to point blank range and firing again, and again.

Octavius Catto fell onto the tracks and into the arms of a white police officer where he died.

“Five years before he had led the efforts to open up the streetcars,” wrote Biddle and Dubin. “Now, as he lay bloodied in the tracks, Octavius Catto saw white and colored riders staring up at him.”

Octavius Catto was murdered in cold blood on a busy street in the middle of a race riot started by white politicians who didn’t want to loosen their grip on power, and carried out by white police officers on their behalf. And he wasn’t the only one.

Frank Kelly, the man who shot Catto, was well known throughout town. He was identified by many witnesses. He fled Philadelphia and was not arrested until six years later when he turned up in Chicago. It will not surprise you to learn that he was acquitted on all charges.

Octavius Catto was 32 years old.

“What are you doing?”

“What are you doing?”

Sports Stories is a free newsletter. But we would like to invite you to consider donating some money or time in the service of civil rights and making the better world that Octavius Catto was trying to get us to. One place to start:

Related Reading

I barely scratched the surface of the surface of Octavius Catto here. Tasting Freedom is both a deeply researched and poignantly written book. The first thing I read on Catto was the SABR bio by Robert Elias. It remains a powerful look into his life, and into the world of baseball in which he operated. I appreciated Jerrold Casway’s “Octavius Catto and the Pythians of Philadelphia” from Pennsylvania Legacies and his SABR story about the first integrated game in Philadelphia between the Pythians and Olympians. Aaron X. Smith’s entry on Catto’s murder in The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia is a useful primer. And the Villanova University libraries have a nice online exhibit about Catto with some cool visuals and primary sources.

Philadelphia unveiled a 12-foot statue of Catto in front of City Hall in 2017.