Welcome to Sports Stories, an illustrated newsletter at the intersection of sports and history. If you’re not already a subscriber, please consider joining up here — we have both free and paid options.

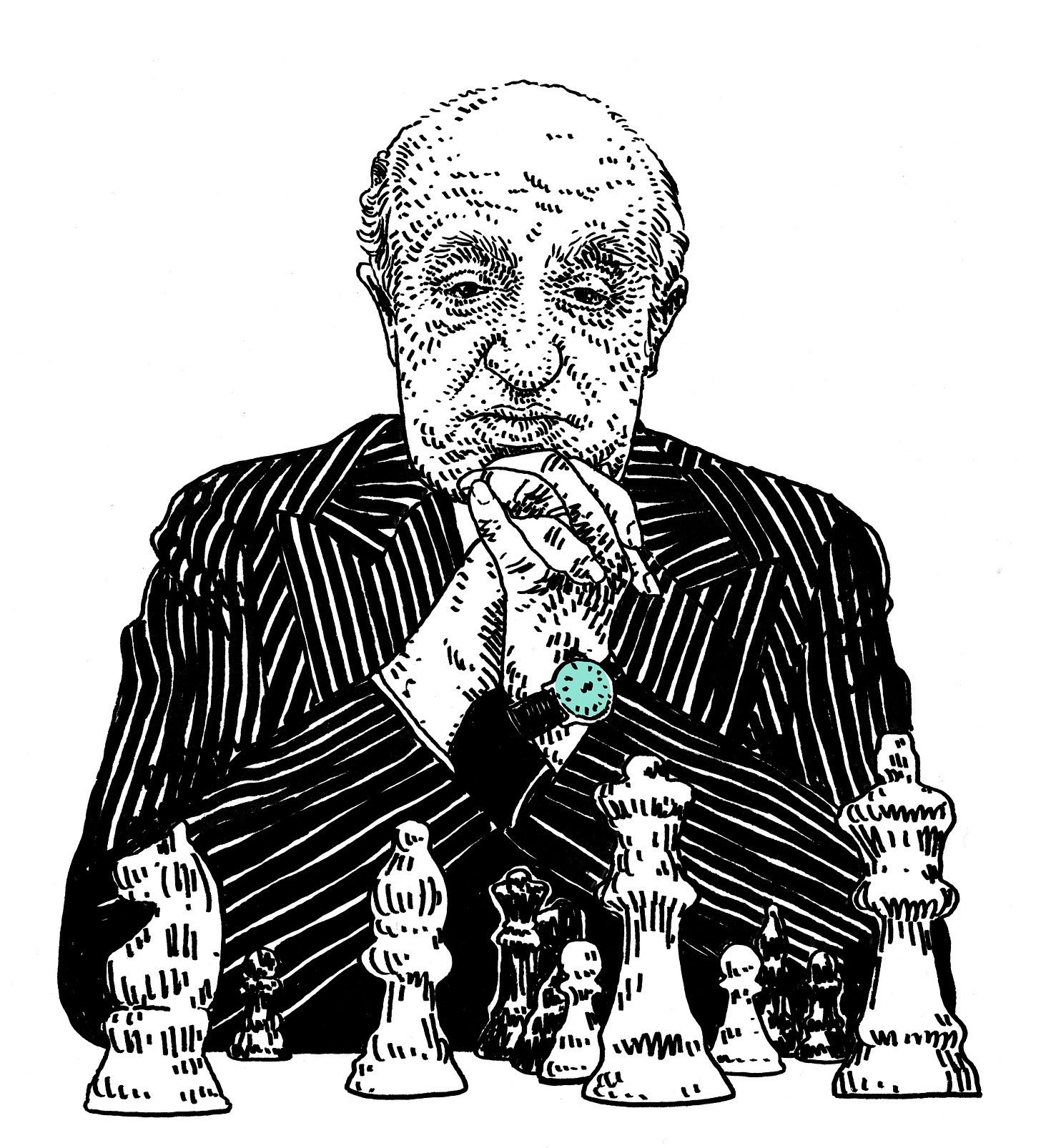

Miguel Najdorf invented a chess opening so great that they named it after him—the Najdorf Variation. It was an aggressive tactic that legendary players like Bobby Fischer and Garry Kasparov adopted. Eventually it became so popular that Najdorf himself had to stop using it.

"Here comes some kid who's memorized the moves and he kills me,” said Najdorf. “He arrives with his books, he gets me into something I don't know and Najdorf dies at the hands of the Najdorf Variation.”

Najdorf was one of the great chess players of the twentieth century, with a ferocious intellect and unmatched memory. He also had a sly sense of humor and an appreciation for irony. He saw the whole board, literally and figuratively. This sense of perspective made it possible to reinvent himself and rebuild his life after suffering a tremendous personal tragedy. Chess itself also made it possible. Chess animated him and gave him a mechanism with which to make sense of the world.

He was born Moshe Mendel Najdorf in Poland in 1910. He learned chess from the father of a childhood friend and became obsessed at a very young age.

“In the early days it was hard for me. My mother even burnt chessboards, books and pieces. Everything. She said that I was possessed, that chess was taking up all my time. She wanted me to become a doctor. I didn’t become one, but now I have two daughters who are doctors. It’s a way of indulging her, isn’t it?”

Despite his mother’s best efforts, Najdorf became a champion and a grandmaster. He was not a doctor, but chess treated him well. He got married and had a daughter. He represented Poland in the Chess Olympiads of 1935 and 1937. The 1939 Olympiad was to be held in Buenos Aires. Initially, Najdorf planned to bring his wife and daughter with him on the trip. But his wife Genia came down with a case of the flu. She decided to stay home with their little girl.

Najdorf and his colleagues, many of whom were Jewish like him, set sail for Buenos Aires in August of 1939. On September 1 of that year, Germany invaded Poland. Poland’s chess team won a silver medal at the Olympiad. Najdorf won an individual prize. Then, days later, Poland surrendered to Germany. Najdorf would not return to Europe to celebrate. He couldn’t. Instead he spent the war in South America waiting for word from his family. Playing chess. Praying for a miracle.

He had no money and no connections in Argentina, so Najdorf simply hustled. He put on a show where he would perform feats of memories for an audience, sponsored by a cooking oil company. He wandered the streets of Buenos Aires learning Spanish.

It was at this time that he began to play blindfold chess. He would play simultaneous games with increasingly large groups, seeing each board only in his mind, and alternating between each opponent. The games drew headlines and broke records. Najdorf would sit in a separate room from the action and call out his moves, rotating through one board after another. Once, he played 45 games at the same time, winning 39, drawing 4, and losing 2.

But it was never just about chess. It was about finding something to occupy his mind, and about trying to reach back to the life he left behind in Warsaw.

“I thought that if I became famous someone in Poland might find out, someone from my family. I went into the insurance business, but I also sold ties, I sold candy, whatever I could sell. In 1946, I returned to Warsaw. There was nobody there. Everyone had died in the Nazi gas chambers. My little daughter too.”

He lost his wife and daughter. He lost his parents and his siblings. There was nothing left for Najdorf in Poland. The great Cuban chess player José Capablanca recruited him to move to Havana, but Najdorf decided to remain in Argentina. He devoted himself to chess and to his new home country. He changed his name to Miguel and became a naturalized citizen. He got a job in the insurance business. He grew obsessed with soccer. He remarried and had two girls—both doctors.

Najdorf was simultaneously a jovial and temperamental man. He loved music and books and the world’s cultures, he loved the fact that chess brought him into contact with powerful people. Once in Cuba, he played a simultaneous game against Fidel Castro, Raúl Castro, Che Guevara, and Camilo Cienfuegos. He played with Perón and Churchill and Khrushchev and the Shah of Iran. He saw himself as an ambassador for the sport, and he was always careful to allow whatever world leader he was playing against the chance to save face with a draw.

Through all of it, he maintained what he considered to be an apolitical stance—at least publicly. His cause, if he had one, was the beauty of chess, the sport that had saved his life. He wrote articles about it. He told stories. He never stopped playing. Even at the end of his life, he would awake each day and look over the chess games published in that morning’s papers.

“What keeps me young is the passion and love for chess.”

Miguel Najdorf died in 1997. He was 87 years old.

Related Reading

Najdorf’s daughter Liliana published a personal and moving biography of her father called Najdorf X Najdorf. It’s full of fascinating anecdotes and intimate details about his life.

I also recommend this long and winding interview from El Gráfico, which was translated and published by ChessBase. It gives you a sense of what Najdorf was like as an older man. Plus you get to read him repeatedly recommending the movie Moonstruck starring Cher and Nicolas Cage to his interviewer.

There is also a Spanish-language book called El Viejo about Najdorf written by a fellow chess player named Zenon Franco Ocampos that will soon be published in English for the first time. I was not able to get a look at it in either language -- but if you’re into annotated games, it could definitely be for you.

Thank you for reading Sports Stories. We’ll see you next week.

witam

kto jest autorem grafiki M Najdorf i czy można do niego kontakt