Welcome to Sports Stories, a publication at the intersection of sports and history. Sports Stories is written by Eric Nusbaum and illustrated by Adam Villacin and delivered to your inbox every Tuesday.

If you’re not already a subscriber, please sign up here — we have both free and paid options. Paid subscribers are entitled to our eternal gratitude as well as cool swag including postcards featuring original art by Adam.

We also have a cool store where you can buy cool hats and shirts.

Late in 2019, I was thinking about writing a Sports Stories about the Washington Generals — the team that exists just to play and lose to the Harlem Globetrotters. The Generals, to me, are a pure expression of love: a group of athletes who work their asses off, travel constantly, and are literally set up to lose every single night for the sake of entertainment and goodwill. To play for them is to be faceless by definition. It is to sacrifice one’s self for the belief that basketball is an inherently positive force in the world.

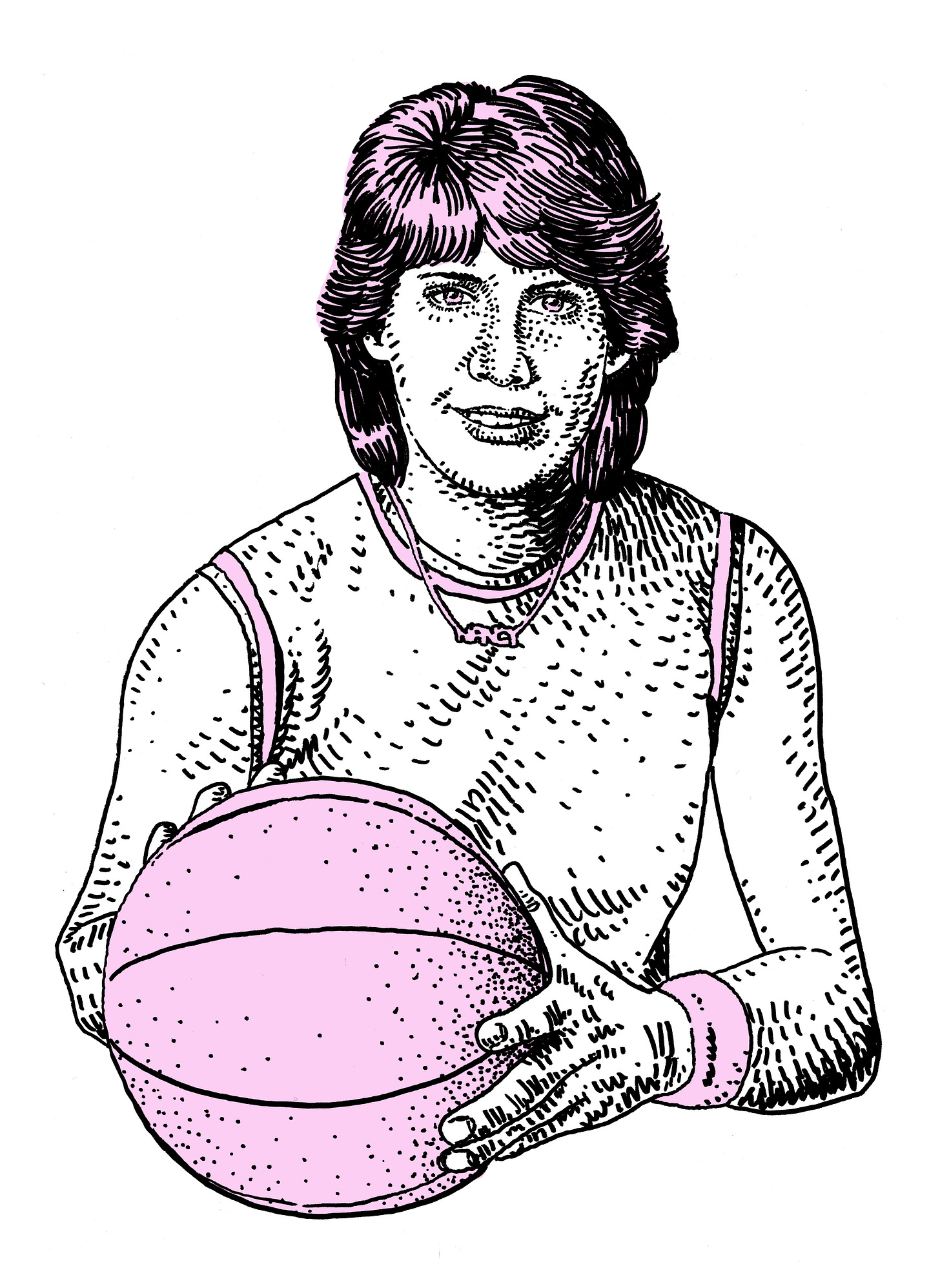

In the course of reading about the Generals, I came across the fact that for a brief period in the 1980s, their roster included Nancy Lieberman. This blew me away. Nancy Lieberman, after all, is one of the greatest basketball players of all time. An Olympian, a two-time college champ, a Hall of Famer. She’s the opposite of faceless: bobbing up and down the court under bright red hair, stalking the sidelines as a coach, or telling stories from the broadcast booth.

It’s not hard to figure out why Lieberman was in a place to play for the Generals: there simply weren’t good professional opportunities for women basketball players in the 1980s. To make it in basketball, to survive in the sport as a woman—even one who could hoop like Nancy Lieberman—you had to be willing to do what it took.

And this interested me too: if you are a high level player in a sport that doesn’t offer high level opportunities for you … what do you do to stick around? What was it like for players of Lieberman’s era to navigate a career as a woman’s basketball player before the WNBA? I was curious enough about these questions that I sent a note to Lieberman’s reps. And Lieberman was kind enough to get on the phone and regale me with some stories about forming a career in an industry that was, at best, unformed.

But we should start at the beginning. The mythical origin story. Nancy Lieberman was born and raised in Far Rockaway, Queens in a household that was unstable and unhappy and unsure what to do with the sports-obsessed girl who played tackle football and baseball and finally basketball against her mother’s wishes. But Lieberman knew what to do with herself. She had something to prove. At twelve or thirteen, she was taking the subway across the city to Harlem, where she’d work her way into pickup games at Rucker Park: the mecca of playground basketball.

She made the US national team as a high schooler. At 18, she became the youngest player to represent the United States in the Olympics and won a silver medal at the 1976 Montreal games. She could have gone anywhere to play college basketball. She chose Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia, because she wanted to build a winner from scratch. She built one: with Lieberman leading the way, the Lady Monarchs won a pair of national titles. Lieberman herself set all kinds of records and was a three-time All-American. People started calling her Lady Magic.

This would prove to be prescient. The summer after she graduated, Lieberman was drafted first overall by the Dallas Diamonds of a new-ish league called the WBL. She should have been back at the Olympics before the WBL season began, but the U.S. boycott of the 1980 games meant she had a few free months. So instead of glory in Moscow, Lieberman found herself playing in a men’s pro summer league at New York’s Xavier High School.

The Xavier league led to her being featured in Sports Illustrated and interviewed on the Today Show. The morning that interview aired, Los Angeles Lakers owner Dr. Jerry Buss happened to be tuning in. A year earlier, Buss had drafted Magic Johnson. He thought—hey, why not see if Lady Magic would want to come out and play summer league for the Lakers.

“Dr. Buss saw it and said something to Jerry West, and the next day I'm getting phone calls from Jerry West,” Lieberman told me. “And he said ‘Hi, we'd like you to play for the Lakers,’ And I'm like ‘Oh my gosh’.”

They sent her a plane ticket, and Lieberman was off to LA. The Lakers summer team that year was coached by a newly hired assistant named Pat Riley. Riley had previously been working as a broadcaster. As Lieberman tells it, he was not thrilled to have her on the team.

When she arrived for her first practice at Loyola Marymount University, longtime Lakers trainer Jack Curran told Lieberman she’d have to use the men’s locker room to change, and handed her an equipment bag with a jock strap in it.

“I held it up and I went, ‘Yo Jack. This thing's too small, I'm going to need something a lot bigger.’”

When Lieberman reflects on her time playing with Riley and the Lakers, she doesn’t sound nostalgic. What she sounds is proud: proud that she earned Riley’s respect, that she outworked every teammate, that she competed in practice and got the ball in games. Playing for the Lakers was not a novelty to her—it was an experience to be taken advantage of; a chance to test herself, to improve herself, to play the game she loved alongside other people who loved it.

In the fall of 1980, Lieberman moved to Dallas and began her career as a pro in the Women’s Professional Basketball League aka the WBL (they dropped the P in their acronym for some reason. The league was only entering its third season, and it was already teetering on the edge of extinction. Lieberman believed she was the kind of player who would put butts in seats. She believed in the future of women’s pro basketball.

“Women’s basketball is not a fad,” she said in a TV interview. “It’s not here and then won’t be. It’s gonna be here for a long time to come.”

Lieberman was basically right. Attendance doubled for the Dallas Diamonds as their new star point guard led them all the way to the finals—where they were felled by the Nebraska Wranglers. (Lieberman was playing through an ankle injury.) Then the league folded. Such was life for women’s basketball players at the time.

She bided her time playing pickup ball. She became a close friend, roommate, and sort of performance guru for Martina Navratilova.

“The league folds and I have nowhere to go,” she says. “So all I’m doing every single day is playing, you know, at the downtown YMCA at lunch, and at the Signature Club at night. All of us would get together and just play ball. And that’s what my life was. I wished that I had a place to play.”

Another women’s pro league popped up in 1984 only to fold after a single season.

“When people thought I was one of the best players in the world, I would have loved to use those skillsets against women so you could actually see my hard work,” she said.

Instead, she played with men. There were two seasons in the United States Basketball League, and there was the stint with the Generals. Initially, Lieberman got a call from the Globetrotters. She was supposed to play alongside Lynette Woodard, the former Kansas All-American who had become the first woman on the Globetrotters. But while Lieberman was in training camp, Woodard quit over a contract dispute. And somehow, Lieberman ended up traded to the Generals.

The thing is, Lieberman explained, that the job of the Washington General is actually in many ways harder. You have to play the straight man during show plays, which guarantee a bunch of points for the Globetrotters, and then outscore the Globetrotters during regular play by enough that the game feels close and has some dramatic arc to it.

“In between, it's real basketball. And in the real basketball, you know, the Trotters were getting old, they really couldn't play at that level consistently. I mean, you know, you play 200 games in six months.”

For Lieberman, who had been a fan of the Globetrotters as a little girl in Queens, it was surreal and magical just to be a part of it.

“The energy. These kids. You were just like rockstars. It didn't matter if you were the Generals or the Trotters. It was a really cool thing.”

Playing for the Generals had Lieberman traveling nonstop and playing nonstop. The schedule—and the nature of the show—forced players to really think about their reasons for being out there. What is the purpose of basketball? What is your relationship to it?

“You have to know what you’re doing and why you’re playing all over the world,” Lieberman said.

During her time with the Generals, they played in the bottom of an empty swimming pool, in the middle of a bullfighting arena, and over a sheet of ice, outdoors, in Newfoundland. Instead of waiting on the bench, reserves would stay in the heated locker room. When the whistle blew, they’d emerge in parkas, and hand them over to the players stepping off the court.

Lieberman stuck around as a player long enough to suit up for the inaugural season of the WNBA at 39 years old. She made another comeback at 50. She became the first woman head coach of a pro basketball team in the United States when she took over the Mavericks’ D-League affiliate Texas Legends in 2009, then the second woman to work as an NBA assistant coach as part of George Karl’s Sacramento Kings staff between 2015 and 2017. She’s worked as a broadcaster for the Thunder and Pelicans and on ESPN. In 2018, she even won a title coaching former NBA stars like Cuttino Mobley and Quentin Richardson in the Big3.

Toward the end of our conversation, Lieberman said that many of the choices she made in her career were not first choices, or best choices, but the only choices. It was a matter of doing anything she could to stick around, to make basketball work for her, even as the institutions of the sport were slow to appreciate her abilities—and even as they continue to lag when it comes to women.

“I just love the game so much. You know, somebody said, ‘Okay, you're coaching the Big3, your doing this that and the other. You're doing TV for the Pelicans. What do you do when you go home?’ I go home and I watch some games.

“I love the game. Whether it's WNBA, NBA, NBA G league, I can identify because I've played in college, I've played in the Olympics, I've played men's minor league. I've coached at every level. There's something very special about every level of this game. The purity of it. I have a lot of gratitude. I don't have any complaints about the game. The game has blessed me, changed my life, took me from a poor kid and gave me things that I never thought I'd have in my life.”

Perfect Profile

No Related Reading section this week, because the bulk of this story comes from Lieberman herself. But I did want to share one other thing about her career. Without the steady salary that a real pro league could have offered her, Lieberman had to be very astute as a self-promoter and business woman. One of those endeavors? Acting.

Lieberman appeared in an episodes of Joanie Loves Chachi and The Cosby Show. She also starred in a forgotten movie called Perfect Profile. There’s a reason Perfect Profile is obscure. It’s the story of a sports owner/playboy in Dallas who wants more than anything to win an NBA championship (only it’s not the NBA due to the obvious copyright concerns). The owner forces a nerdy scientist who works for him get to work at figuring out what his struggling team needs.

The scientist employs a truly unspeakable combination of eugenics and sabermetrics to find the perfect profile — aka the player who will mesh with the team in a way that absolutely guarantees a title. But in a twist, that player is a woman. You’ll never guess what happens next. For some reason, the whole thing is on YouTube:

Thank you for reading Sports Stories. We’ll see you next week.