Welcome to Sports Stories, a publication at the intersection of sports and history. Sports Stories is written by Eric Nusbaum, illustrated by Adam Villacin, and delivered to your inbox every Tuesday.

If you’re not already a subscriber, please sign up here — we have both free and paid options. Paid subscribers are entitled to our eternal gratitude as well as cool swag including postcards featuring original art by Adam.

On May 27, 1981, a businessman named Roger Wheeler finished his weekly round of golf at the Southern Hills Country Club in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He got into his Cadillac and was preparing to pull away -- back to his office or his family or to wherever a wealthy executive might go on a Wednesday afternoon -- when a strange man approached the car and shot him in the head.

The murder of Roger Wheeler would soon result in two more murders -- both instigated by notorious Boston mobsters Whitey Bulger and Stephen Flemmi, and both in the service of protecting the fortune their gang was making on a traditional Basque sport called jai alai.

We’ll get back to the Boston guys in a second, but first jai alai. Wheeler’s murder was either a dark sign that this beautiful and strange sport had finally made it in America or a warning that the corrupt nature of its institutions would prevent jai alai from becoming anything more than a niche form of entertainment. Maybe both.

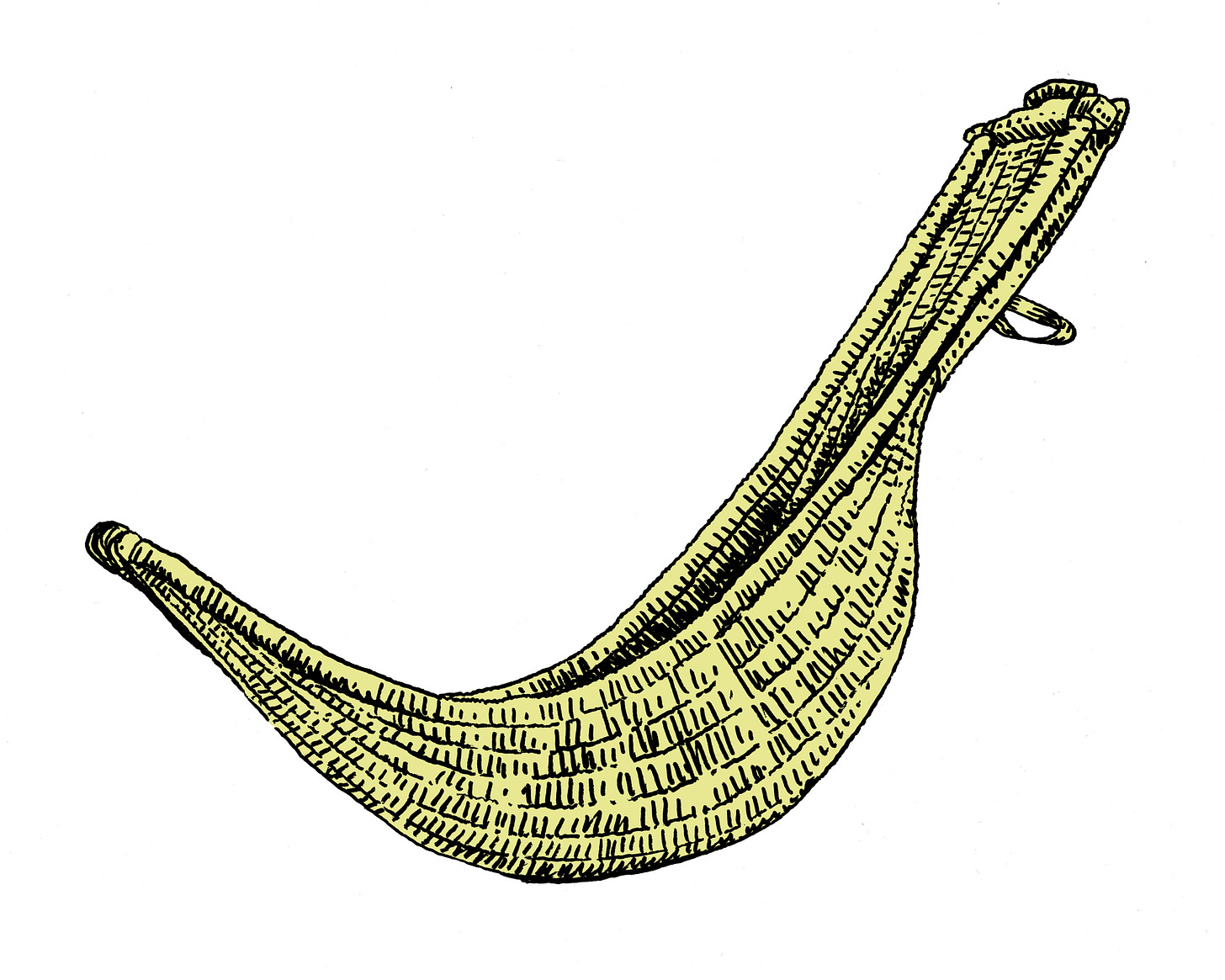

The sport looks a little bit like racquetball, but played on a bigger, more open court -- and instead of rackets, players carry big curved baskets called cestas that they use both to catch the ball and to hurl it back at the wall at speeds upward of 150 miles per hour. It is fast, dangerous, and tremendously entertaining.

The first jai alai fronton in the United States (the fronton is technically the playing field, but the term is also used to describe the venue itself) was built for the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. But by then, jai alai had already caught on in Cuba. The Havana fronton was known as El Palacio de los Gritos, or The House of Screams.

The name probably tells you all you need to know about the action of jai alai. But the other important thing to know is that for all the grace and athleticism you might see in jai alai, the sport’s primary purpose in America is to serve as a platform for gambling. Jai alai isn’t organized like traditional winner and loser sports. Matches (usually doubles) involve eight teams rotating in and out as points are won and lost. Each match ends with the teams in a ranked order. Bets are placed as they would be on horse races in a parimutuel style. You can pick not just a winner, but a second, third, or fourth place finisher.

Jai alai took off in Florida in the 1920s, and gained popularity over the years as a novel form of entertainment and lucrative business for promoters and bookmakers. It was a uniquely insular sport. Nearly all the players were imported to American frontons (mostly in Florida, but also occasionally in Connecticut, Nevada, and other states) directly from the Basque Country. They were paid little and treated poorly. In 1968, Basque jai alai players organized and went on strike. Management dealt with this by simply replacing them with other Basque jai alai players.

These labor problems did not hinder the sport’s growth, especially in Miami, where jai alai would regularly draw crowds of more than 10,000. As jai alai grew more popular, the state of Florida loosened up gambling laws in order to make betting on it more accessible. Florida law also held that parimutuel betting sites like jai alai frontons were allowed to run casinos -- making them even more lucrative for business owners and even more popular for fans. What had begun as a traditional Basque sport had over decades evolved into an institution that embodied the speed, glamour, and excess of Miami in the 1970s.

The excess part is what brings us back to the Oklahoma businessman, Roger Wheeler. The institutions of jai alai were corrupt by their very nature, and regulating frontons was a nearly impossible task for state governments and gaming commissions. They tried to weed out corruption, but they were often a step or two behind. In 1976, gaming regulators in Connecticut demanded that the president of a large promoter called World Jai Alai step down from the company. World Jai Alai was a major operation, with a portfolio that included four frontons in Florida and another in Connecticut.

The man the regulators forced out was a Boston hustler named John Callahan. Callahan was a big, affable guy with direct ties to the mob. He had built the entire World Jai Alai operation in his own image: he hired an ex-FBI agent named H. Paul Rico to run security, brought on a fancy computer consultant, and gave his Boston buddies cush jobs.

That same year, the owners of World Jai Alai decided to sell the business. They had a hard time finding a buyer who would satisfy regulators. Their first candidate was a fellow named Jack B. Cooper. Cooper turned out to be a convicted felon and close personal friend of the legendary mobster Meyer Lansky. Their second candidate was the Bally's Corporation. But Bally’s had its own mob ties -- it would have been a bad look to sell to them.

Which led them to Roger Wheeler. Wheeler was said to be a religious man, by no means a gambler. But he was also a dealmaker. He liked to make money, and in parimutuel betting, he saw big possibilities. Wheeler purchased World Jai Alai for about $60 million in 1977.

But it wasn’t just World Jai Alai that Wheeler got. Before he left the company, John Callahan had installed a complex system that allowed him and his associates Whitey Bulger and Stephen Flemmi to skim upwards of a million dollars off the company books every year. Remember H. Paul Rico, the ex-FBI agent who Callahan had hired as head of security? He was in on it too.

It did not take long for Roger Wheeler to figure out that there were irregularities in World Jai Alai’s finances. But the terms of the loan he had used to purchase the company made it hard for him to rid himself of Callahan’s associates. Still, he worked hard to sort things out. Wheeler couldn’t shake the the feeling that he was being taken. And even worse, he was growing increasingly suspicious that the people doing the taking were connected to organized crime.

Here’s the Hartford Courant:

Events connected with Connecticut's fledgling jai alai industry could not have been reassuring. The state police had redoubled investigations of possible game fixing, suspected skimming and possible links to the Winter Hill Gang. By 1980, Wheeler had decided to sell the Hartford fronton. He hoped such a move would cut World Jai Alai's geographical link to the New England Mafia, while grouping his four remaining frontons in Florida.

Wheeler spoke continually with Connecticut State Police detectives. He recorded his telephone calls and trained his staff in stress analysis so they could review the recordings and speculate about who was lying to him. He became so concerned for his safety that he once had his pilot take his private jet up for a spin around the airport in Tulsa before he boarded a flight to Connecticut.

Wheeler had good reason to be nervous. In Boston, Callahan began to fear that Wheeler was close to discovering the skimming operation. That would have meant a huge financial hit not just for Callahan, but for his partners, Bulger and Flemmi of the Winter Hill Gang. There also would have been legal scrutiny that none of them wanted. In a meeting, Callahan talked Bulger and Flemmi into murdering Wheeler -- a task that would be made easier with the cooperation of Wheeler’s head of security, H. Paul Rico. With Wheeler gone, Callahan believed he could not only protect his embezzlement scheme, but regain control of World Jai Alai.

There was also a third man present at the meeting: an enforcer named Brian Halloran. Bulger and Flemmi decided that Callahan was right, Wheeler had to go. But instead of Halloran, they would use a hit man named Johnny Martorano for the job.

"I saw a guy coming over the hill carrying a brief case," Martorano said in court decades later. “It looked like him. He was heading toward that car. So I head toward that car. He opened the door and got in. So I opened the door and shot him. Between the eyes."

But the Wheeler murder didn’t solve Callahan’s problems, or the Winter Hill Gang’s. It only compounded them. Halloran, for one, became an undercover informant and developed plans to give up the gang in exchange for his own immunity, using his knowledge of the Wheeler case as evidence. This backfired, however, because Bulger found out about it from (another) corrupt FBI agent. Bulger then solved that particular problem by shooting Halloran in broad daylight on the Boston waterfront.

Meanwhile, Callahan was not getting any closer to regaining control of World Jai Alai. Instead, he was feeling the heat from law enforcement himself. The cops knew that Callahan, Bulger, and Flemmi were behind the Wheeler hit somehow. But they didn’t have all the pieces they needed to make a case. They didn’t have a witness to testify. Bulger and Flemmi were hardened killers -- hard to bring in, and theoretically hard to flip. (They were also working under FBI protection, as we now know). But Callahan? He was a soft target.

Bulger and Flemmi were concerned that Callahan would buckle. Then they got word from their FBI source that it was happening. Callahan was going to testify against them. Jai alai was a beautiful sport, and had made the Winter Hill Gang tidy profit. It was certainly worth killing for, but it wasn’t worth dying or going to prison for. The best thing would be to cut ties with jai alai altogether and move onto something else. So Bulger and Flemmi turned back to Johnny Martorano.

"I objected," Martorano said in court. "Callahan was a friend of mine. I had just killed a man for him, risked my life. I didn't want to kill Callahan. Eventually, they convinced me. It was two against one and it was three of us. And I finally agreed, 'It has got to be done. It has to be done.'"

The chain of violence that John B. Callahan unleashed in order to protect his jai alai embezzlement scheme had come all the way back around. Callahan’s body was soon discovered in the trunk of his car in the Miami airport. Like Wheeler, he had been driving a Cadillac.

Jai alai

Jai alai is still going (though I wouldn’t say it’s going strong). The sport hit its peak around the time of the Wheeler murder. Slowly, it began to fade in popularity. In the late 1980s, jai alai players conducted the longest strike in the history of pro sports, lasting about three years. These days, it’s mainly a Florida thing. Here is a delightful video of former SportsCenter guy Kenny Mayne attempting to play jai alai, and also attempting to gamble on jai alai. It also makes a pretty good explainer.

Or, if you want to see the sport being played beautifully, and looking more like it might have during the heyday of World Jai Alai:

The Winter Hill Gang

A lot of the info in this week’s newsletter came out during the Whitey Bulger trial in 2013. This is not really the right space to get into it, but the story of how the FBI mishandled Bulger and Flemmi in the 1970s and 1980s is a fascinating indictment of American law enforcement. The short version is that Bulger and Flemmi were both working as FBI informants throughout their violent, lucrative careers and consolidated power by manipulating the agency into locking up their enemies. Apparently some of this stuff was featured in the Johnny Depp movie Black Mass, but neither Adam nor myself have seen it.

Some of my favorite reporting on the Wheeler murder, and the ensuing chain reaction of violence comes from the Hartford Courant. Our story barely scratches the surface. But in general, this story has been covered extensively. The murders were big news at the time, and they became big news again after Bulger was arrested.

I also really enjoyed this reminiscence from Robert Sullivan at Time. He writes about covering the Wheeler murder as a rookie reporter at Sports Illustrated, initially thinking it was just going to be a quick story about an odd murder at a golf club, quickly realizing the sport here was jactually ai alai, then learning that well, this might be bigger than just jai alai. You can also go back and check out Sullivan’s original reporting on the murder, which holds up quite well.

Bulger died in prison in 2018. Flemmi remains in federal custody. And Johnny Martorano, the hit man who shot Wheeler and Callahan, is living quietly in retirement after testifying against Bulger and Flemmi. (He served a relatively short prison sentence, considering that he confessed to killing 20 people.) Martorano chose to testify because he felt betrayed when he learned that Bulger and Flemmi had been FBI informants all along. “It sort of broke my heart,” he said.

Thank you for reading Sports Stories. We’ll see you next week.

Hi Eric, Thanks for this terrific article. I just linked to it in a piece over on my Substack thing here. I really don't know these ropes yet, but I thought you might enjoy it, should this work. Keep up the fine work. Here's this thing, I guess: https://substack.com/home/post/p-144181513?source=queue (BTW, Can the Dodgers give us Mookie back?)

great blog, excellent art. one of my favorites so far. and just since no one else dropped it in:

https://youtu.be/tAZ-VZlEZMQ?t=429