Twisted Steel and Sex Appeal

The ballad of Sputnik Monroe, wrestling heel and unlikely civil rights champion

Welcome to Sports Stories, a newsletter that explores sports and history at the intersection of everything. If you’re not already a subscriber, you can sign up here.

Sputnik Monroe is a goddamned time machine. His life will take you back to the old, weird America, to a time when the country was both a bigger and a smaller place. It’s an impossible story, which means that at least some of it must be true. Sputnik Monroe died in 2006, but he lives on in the precipice between reality and myth.

His name wasn’t always Sputnik. It was Roscoe Monroe Brumbaugh. Roscoe was born in 1928 in Dodge City, Kansas, the former frontier town where Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson once strutted down the dusty streets and gunshots rang out across the plains. But Roscoe wasn’t made to be a sheriff or a cowboy or a baker like his stepfather. He wasn’t made for Dodge City, Kansas either.

When he was 17, Roscoe took off and joined the Navy. He was a barrel of a man, fearless and endlessly energetic. After his stint, he came back and he did the obvious thing for a person of his talents: he hitched up with a traveling carnival. He had been a high school wrestler and found that he could hang with all the strongmen and brutes on the circuit. And more importantly, he knew how to put on a show. For five years, Roscoe traveled America fighting local tough guys every night, taking on all comers, and embracing the role of the villain in every town he was in.

“I had shovel fights, rope fights, pick-ax handle fights, wrestled, boxed, one hand tied down, whatever their specialty was,” he said.

As professional wrestling grew in popularity in the 1950s, Roscoe transitioned from the carnival to the ring. He took on different names: first Pretty Boy LaRocque, then Rock Monroe (if you say it fast, it sounds like rock n’ roll). Supposedly he was hit in the face with a wooden chair, and the surgery to remove the splinters from his skull left a streak of blonde hair at the front of his head. This would be part of his trademark.

In 1957, Roscoe found himself on a long haul drive from Seattle to Mobile, Alabama to appear live at a TV station ahead of a match with Gulf Coast Championship Wrestling. (Until WWE consolidated the business in the 1980s, wrestling was a regional sport: the country was partitioned off into territories, each with their own unique style).

Up until this point, Roscoe’s gimmick was pretty standard villain stuff: he strutted across the ring. He was 200 pounds of twisted steel and sex appeal. He was a “diamond ring and Cadillac man.” Roscoe wasn’t a technically brilliant wrestler, but he was tough as shit and he could make the crowds feel something. He had a gift for working a room, for pushing people further than they realized they could be pushed.

As the legend goes, Roscoe ran out of steam in Greenwood, Mississippi. So he picked up a hitchhiker asking the man if in exchange for a ride, he could drive Roscoe to the TV interview in Mobile. “And after it’s over and I woke up,” he told NPR years later, “we’ll go rock and roll with the ladies on the street.”

When they arrived, Roscoe put his arm around the hitchhiker’s shoulder and they strolled together into the station. The thing was, this was Alabama in 1957 and the hitchhiker was a Black man. When the live audience there for his interview began to hoot and holler and call him names, Roscoe pulled his new friend back on stage and gave the man a kiss on the cheek.

Here’s Roscoe in his own words:

“One old lady cussed better than drunk sailors. She’s calling me an ‘n-word lover’ and finally the security told her if you don’t stop cursing we’re going to have to ask you to leave. And she said what he really is is a “damn Sputnik.”

The Soviet satellite had been launched that week. And Roscoe Brumbaugh aka Pretty Boy LaRoque aka Rock Monroe had finally come upon the nickname that would cement him as an all time legend of wrestling. He would be Sputnik Monroe, no good commie integrationist who signed his name with a hammer and sickle and hung around with mixed company.

Sputnik found his greatest fame in the years to come in Memphis. He embraced the city and threw himself into its cultural life in a way that went beyond just his role in the ring. He palled around with Sam Phillips, the founder of Sun Records who recorded Elvis and Johnny Cash. He hung out on Beale Street, back before it was a tourist attraction and when white people were expected to keep their distance. At first, he was known for his rivalry with a fellow wrestler named Billy Wicks. The pair (plus guest referee Rocky Marciano) set an attendance record for an outdoor match in 1959 that stood for 40 years.

But these days, Sputnik Monroe is known more for his persona and for his activism than for his actual wrestling prowess. He’s credited in various articles as the hero who integrated pro wrestling crowds in Memphis; as an unsung civil rights activist. But I hesitate to write about him this way. First, because I can’t find any record of Sputnik identifying himself as a hero -- if anything I think such a designation would have made him uncomfortable. “I’m not a do-gooder, he once said. I’m a doer. Just a doer.” Second because the stories that portray him this way are largely devoid of Black voices and I’m wary of white savior type narratives. And third, because it’s genuinely hard to disentangle the character with the man.

My initial suspicion was that Sputnik Monroe was simply doing what he could to piss off white wrestling crowds, generating heat for matches and building his brand as a heel in the white world of wrestling. But the more I read about him, the more I came to believe there was a lot of sincerity in his schtick; that Roscoe Brumbaugh really became Sputnik Monroe. The character Sputnik was borne of Roscoe’s genuine beliefs about race and injustice in America. And as Sputnik, he genuinely put himself on the line. He was repeatedly arrested for his trouble. “They charged me with ‘mopery and attempted gawk,’ that’s an old Southern thing they made up,” he told the writer Robert Gordon, who featured Sputnik in his book It Happened in Memphis. “I was on Beale Street every night for the first six months. I got arrested three or four times until that didn’t work out and then the cops left me alone.”

In 1959, Sputnik appeared in the pages of the city’s leading Black paper, the Memphis World in a photo with an immensely popular radio DJ named Dick “Cane” Cole with the headline “Mutual Admiration Society.” Sputnik’s meeting with Cole was relegated to the top of page 3. The front page was devoted to a visit that week from Martin Luther King Jr. who was in Memphis to host a rally on behalf of local Black candidates for office. One of those candidates was a Harvard-educated attorney named Russell Sugarmon Jr. who was running what would ultimately be an unsuccessful race for Public Works Commissioner.

A few months later, Sputnik would suffer his first Memphis arrest for drinking on Beale Street. He breached protocol once again and hired Sugarmon to be his lawyer. “Wrestler Monroe Fined: He was in Negro Cafe,” went the headline on an Associated Press story the following day. The article is worth reading in its entirety, but here are two choice lines:

“After court, City Judge Boushe said it was the first time a white man was represented in City Court by a negro attorney.”

“Sugarmon asked what the disorderly charge was based on. The officers said it was simply on the fact that he was drinking in a negro cafe with negroes.”

As Sugarmon pointed out in court, Sputnik had developed a large following in the Black community in Memphis. He was a genuinely wonderful showman. He once dyed a goose’s feathers pink and put a rhinestone collar on it and walked it like a dog down Beale Street. He did things other white people in the segregated city were simply not willing to. But it’s also worth noting that he was able to do these things because he was white. Sputnik Monroe could go drinking on Beale Street, find himself welcome in bars and cafes, and come away with a $26 fine and some good publicity. But a Black wrestler couldn’t do the same thing in a white neighborhood. The bars and cafes wouldn’t let them in the door.

The Ellis Auditorium, where most of his matches were held, was segregated. Black fans were allowed to enter only in limited numbers and forced to sit high up in a tiny balcony section . This apparently did not sit well with Sputnik, who voiced his opinion to promoters and threatened to stop wrestling before segregated crowds. When they did not listen quickly enough, he took matters into his own hands.

The segregation policy at the Ellis was enforced at the front entrance, where there were two bouncers: one counting white fans, and one counting Black fans. Sputnik started slipping cash to the bouncer counting the Black fans so that he would let more in than he was supposed to. As Jim Dickinson, a musician, producer, and Sputnik superfan, told Robert Gordon, “Finally the audience got so big and so heavily Black that they had to integrate the seating.”

Dickinson (who would go on to play piano on the Rolling Stones’ “Wild Horses,” and produce albums for Big Star, Toots and the Maytals, and the Replacements among others) was typical of Sputnik’s other fanbase: rock n’ rollers, hippies, and other rebellious white kids. Sputnik became a counterculture hero. High school yearbooks in Memphis during his reign were scattered with photos of otherwise square looking white kids with a streak blond dyed into their dark hair.

I mentioned before that I could find very few primary sources with Black voices talking about Sputnik. However, his ex-wife Midge Bell and daughter Natalie spoke to the AP a few years ago and recalled getting death threats and having their house egged. It got to the point that they changed the kids’ last names from Brumbaugh to Bell.

Sputnik left Memphis in the early 1960s to try and make a go of it nationally, but his career never quite took off. The wrestling business was still divided into fiefdoms: going over big in Memphis didn’t mean anything in Detroit or Denver or Houston.

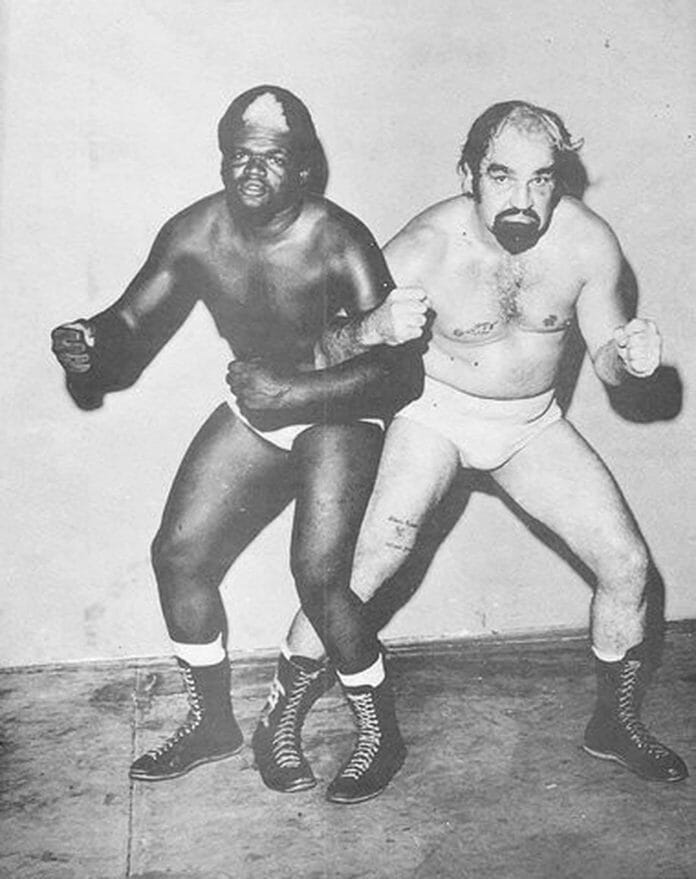

In the early 1970s, he wrestled as part of a tag team with an up and coming Black wrestler named Norvell Austin. Austin dyed a streak of blonde in his air just like Sputnik’s. Before matches, Sputnik would declare “Black is beautiful” and Austin would respond “White is wonderful.”

They were, of course, meant to be the bad guys.

Reminders!

Thank you to all the folks who have shopped at the Sports Stories store. We’re both super appreciative of your support and super stoked that you would want to wear a hat or shirt that says “Sports Stories” on it. Remember these are limited run items, so if you’re thinking about getting, say, this particular Sports Stories hat, now is the time.

If you’re interested in supporting the newsletter in other ways, remember you can:

A.) Share this newsletter with a likeminded friend or on social media.

B.) Sign up to be a paid subscriber. Sports Stories will always be free, but your support allows us to spend more time on it every week and make it as special as we possibly can.

Finally, if you are already a paid subscriber, please fill out this short survey so we can send swag your way.

Related Reading

One thing I love and appreciate about pro wrestling is that there are thousands of superfans and historians out there maintaining diligent records of every single thing. These folks appreciate characters. Which is to say, there’s a ton out there on Sputnik Monroe. I would start with Robert Gordon’s book It Came From Memphis. I’ve only been to Memphis once -- for a few days on a work trip -- but man, what a hell of a city. I loved it.

I really appreciated the NPR stories I found on Sputnik in particular because it’s great to hear his actual voice, gruff and also tender in recalling his career. This 2018 AP story by John Sharp also provides a good overview of his career.

Sputnik was also interviewed for an oral history book called My Soul Looks Back in Wonder: Voices of the Civil Rights Movement. He talks about how his grandpa taught him to box and the experience of returning to Memphis years after his run there only to find himself getting a totally unexpected hero’s welcome.

One thing that struck me about Sputnik as I researched his career was the way that people absolutely loved him in a deeply personal manner. He had an effect on people. He retired from wrestling after a car accident in 1977 and lived out the rest of his life in different Texas cities, working as a security guard and doing other odd jobs. To get a sense of Sputnik the man, check out the comments on this blog post marking his death in 2006: friends, relatives, people he met just once, all gathering to cherish this man. The first post was by his longtime Memphis rival, Billy Wicks.

HE WAS MY HERO, NOT MY ROLL MODEL,BECAUSE HE FEAR NO ONE. MUCH RESPECT,I LOVE HIM LIKE MY BROTHER,I CURST HIM BECAUSE WE HAD A DEAL HE WAS SAPPOSE TO READ MY OBITUARY BEFORE I READ HIS.

As noted above, Sputnik hung around with musician types. He also cut one of the first novelty songs by a pro wrestler. It was an improvised bit called “Sputnik Hires a Band.” The premise is that he wanted a rock n’ roll band, but instead got a bunch of square hornblowers and violinists. He spends the entirety of the song yelling at them:

Finally, here’s a video of the man in action:

Thank you for reading Sports Stories. We’ll see you next week.

This was just an excellent read. Researching Sputnik or any of the wrestlers who made their names before TV (or of no remaining TV) is a tough slug. My compliments.