We Can Be Heroes Like Shavarsh Karapetyan

I wish you could swim. Like the dolphins, like dolphins can swim.

In bad times, we crave good stories. We crave myth. We crave heroes. Like right now, I bet you can’t turn on the TV or open up your social media narcotic of choice without coming across some kind of article or news clip about “pandemic superheroes.” And honestly, I get it. It helps to be reminded that a.) there’s good people out there and b.) those good people might just be us.

Well, there are good people out there. I think most of us are good people, and that’s true whether we’re working in nursing homes or hospitals or supermarkets, or whether it feels like we’re just barely hanging on at home. In fact I would go so far as to say that these reminders of the goodness of people, and of our capacity for exceptional acts of selflessness are more than a nice thing -- they are a borderline necessity. Chicken Soup for the Soul etc etc.

The flip side, of course, is that it’s very easy to leverage stories of heroic acts for nefarious purposes. Sometimes the very notion of “good” is subjective. We currently have a president who is telling us that going out into the world to possibly contract and spread a terrible disease makes us warriors for the economy. It’s easy to cast any kind of behavior as heroism, is what I’m saying, if that’s what you want to do.

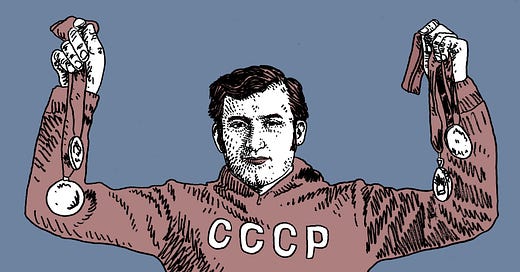

I say all that so we can talk about the Armenian swimmer and genuine hero Shavarsh Karapetyan -- but also about the strange way his heroic act was manipulated by forces much larger than he was. Shavarsh Karapetyan was one of the greatest athletes in the entire USSR. He saved dozens of lives in a ridiculous feat of strength, skill, and endurance that was only possible because of his years of hard work and training as a Soviet athlete. Then he saw the feat completely erased from memory for years -- only to suddenly, years later, become recognized for it.

Shavarsh Karapetyan was born in Armenia. He grew up first in a small mountain town, and later in the capital city of Yerevan. He was the oldest of three boys, and their father insisted that all three would be athletes. Shavarsh was a monster of an athlete, even as a young boy, but he was just a smidge too late getting into organized sports -- especially considering the nature of the Soviet sport apparatus, in which children were trained and molded from a very young age. He bounced from gymnastics to swimming, and finally, when he was 17-years-old, to a niche water sport called finswimming. (It’s exactly what it sounds like: swimming underwater with either multiple fins on, or one giant fin like a fish.)

Finswimming suited Shavarsh: he was a thick, explosive type of athlete. He was more powerful than he was graceful. The culture around the sport suited him too. In a wonderful story for Grantland, the writer Carl Schreck described in painful detail the kind of workouts Shavarsh put himself through under the guidance of his mentor Lipo Almaskayan. (I promise there’s a reason I’m sharing this paragraph):

Much of the training took place out of water, colossal strength work that became legendary in Armenian sports circles. He would run 12 to 18 miles a day, often loaded down with a sand-filled backpack. There were rowing workouts on manmade Lake Yerevan, which was forged a decade earlier and had already become so inundated with industrial runoff that only the drunk or the indifferent dared swim in it. Lipo also concocted experimental exercises for his pupil: He affixed planks of wood to cross-country ski boots and made Karapetyan jog in them to improve his foot strength. Karapetyan would carry a fellow swimmer on his shoulders while running hills along the shore of Lake Yerevan, or he’d climb those same hills on his hands while a teammate held his legs, wheelbarrow-style.

Unsurprisingly, Shavarsh became a superstar finswimmer. He cleaned up at every tournament. He won gold medal after gold medal. Then, suddenly, in 1976, he was unexpectedly dropped from the national team. This made no sense. He was only 23 years old. He was at the top of his game. He had broken world records.

The only way Shavarsh knew how to respond to the sleight was through even harder, even more miserable, even more grueling training. On September 12, 1976, Shavarsh was in the midst of a long evening run through Yerevan with his brother when they heard the sounds and saw the sight of a trolleybus plunging into the city’s principle body of water, the man-made Lake Yerevan. As Schreck details, Lake Yerevan was a polluted and miserable lake, unfit for swimming.

But Shavarsh ran down to the shore, dove in under the water, kicked in a window of the trolley, and began to pull people out. There was an air pocket in the vehicle, and the passengers were smashed up desperately in it, struggling for the little bit of oxygen that they still had. One at a time, Shavarsh hauled people out of the toxic lake, handing them off to his waiting brother who had dived behind him. Again and again and again. He saved thirty lives that way. Another 60 were beyond saving.

Then a strange thing happened: the accident was blacked out by the media. The reason? It was apparently inconceivable that a Soviet trolley could crash. To cover Shavarsh’s heroism would also mean acknowledging that the government was capable of failure. The lives Shavarsh had saved were real. There were dozens of people still breathing who would not have been if Shavarsh had not pulled them from the sinking trolley. But the act itself “did not happen” -- coverage of the accident was kept to a few paragraphs in the local paper. and the rescue went unmentioned

Shavarsh himself was nearly another victim of the trolley accident. He caught double pneumonia. He was delirious and feverish and he was hospitalized for a month. He was bedridden for longer. A lesser athlete could not have saved those people, and even if they could have, a lesser athlete may not have survived the rescue. Shavarsh survived. In fact, he forced himself back to health. But he was not the same person afterward. The water, the very act of swimming, became sources of pain to him. He hated it. But he did it anyway. Something compelled him to complete the task he had set out before the accident. After all, as far his critics and competitors knew, there was no accident. If he failed to regain his form, they would never understand why. But of course he succeeded. Of course he willed himself through the misery and returned to finswimming and broke another world record.

Then, in 1982, Shavarsh finally became a hero, in the official sense. It’s impossible to say why. Maybe enough time had passed since the accident. Maybe somebody high up in the government just really loved finswimming, or made the calculation that a hero was needed. Newspaper and magazine writers began to show up in Yerevan asking questions, and for the first time, the local government began to answer them. They handed over the reports on the accidents. Shavarsh’s exploits were recognized across the USSR and he became a far bigger celebrity than he had ever been as a swimmer.

In the years after his heroic acts, Shavarsh seems to have bounced around. He appears briefly in some academic articles about local politics in Armenia after the fall of the Soviet Union. He was recently named a special advisor to the head of The Republic of Bashkortostan (in Russia). The effects of his heroic act have not worn off -- not for the people he saved, and all the lives around them that he touched -- and not for the governments that still see a way to borrow some of his sparkle.

Shavarsh is still a good reminder that there’s more good stuff happening in the world that we might be aware of. Just because we don’t hear about it, doesn’t mean the tree didn’t fall in the forest etc. Just because there’s bullshit everywhere, doesn’t mean there aren’t good people risking it all and doing the right thing.

Related Reading

Most articles about Shavarsh out there are just vague recountings of the mythology. But Carl Schreck’s Grantland piece is a truly impressive piece of historical journalism. Plus it has great visuals.

This is a Russian documentary about Shavarsh, and even without speaking Russian, I can tell that it’s wonderful:

Also

Thanks to my cousin, Cary Polin, for telling us about Shavarsh. If you have any ideas or suggestions for Sports Stories, please feel free to reply to this email, or hit is up on social media and share them with us. We love getting your ideas.

This is the 30th edition of Sports Stories (not counting minor emails and updates). Adam and I are still having a lot of fun bringing these to you every week, and it’s been great to watch our tiny newsletter grow. If you are enjoying Sports Stories, please don’t be shy when it comes sharing these posts with friends and family, or better yet, telling them to sign up.