This week, the NHL playoffs were supposed to start. It’s hard to imagine now, and I had to look at a calendar and double check to make sure I wasn’t imagining this. Then that small act of remembering something that was supposed to happen set me on the path to wondering whether this whole exercise, thinking about what should have been, was in fact unhealthy. The NHL playoffs of all things? I mean who cares. The world has split into a before and an after. And all the afters that were once possible are now gone forever.

Still, it’s hard not to linger. The hockey playoffs are my favorite. They are this grueling, horrible, wonderful thing. At least they seemed grueling and horrible before. One of the inverse blessings that not having sports offers us is the opportunity to reflect on what it was like when we still did have sports. Sports, when we still had them, offered us ritual.

A few weeks ago I wrote that sports are a way of marking time. But they are also a way of filling time: the familiar rhythms. They offer us the simple gift of things to do: as participants and spectators. They offer us habits. We are a species that craves ritual, that requires it. And in sports, ritual can create meaning where there otherwise isn’t any. We wrap our games up in fancy clothes and they become important. But they aren’t actually important. That is a big part of their appeal, even at their most serious.

So anyway, the hockey playoffs were supposed to be starting, and I’m missing that, and I’m missing the ritual. And I was thinking about the most frivolous, and fun, and beautiful ritual in hockey. This is a sport built on ritual, after all. Taping blades. Lacing skates. Putting on pads one clasp at a time. This is a sport that requires so much work just to exist. It is played on a man-made sheet of ice inside a giant building that is literally a refrigerator. Think about how much energy that requires; both the global warming kind, and the humans working at the rink kind.

This is a sport that requires a break in the action just so a giant, complicated machine can enter the field of play and slowly, like a hippo gliding across the surface of a pond, make it suitable for Alex Ovechkin and co. Yes. I am indeed talking about Zambonis. I want to be in a world where I can watch a Zamboni making concentric circles and be hypnotized by it. That’s all I want.

The other thing about Zambonis is that they actually represent a more functional world. The Zamboni is a beautiful American success story. It may not be elegant physically, but it is elegant in that it is the product of a society working as it should. It is elegant in that it was invented to solve a problem, and that since it has come into the world, that problem has been solved.

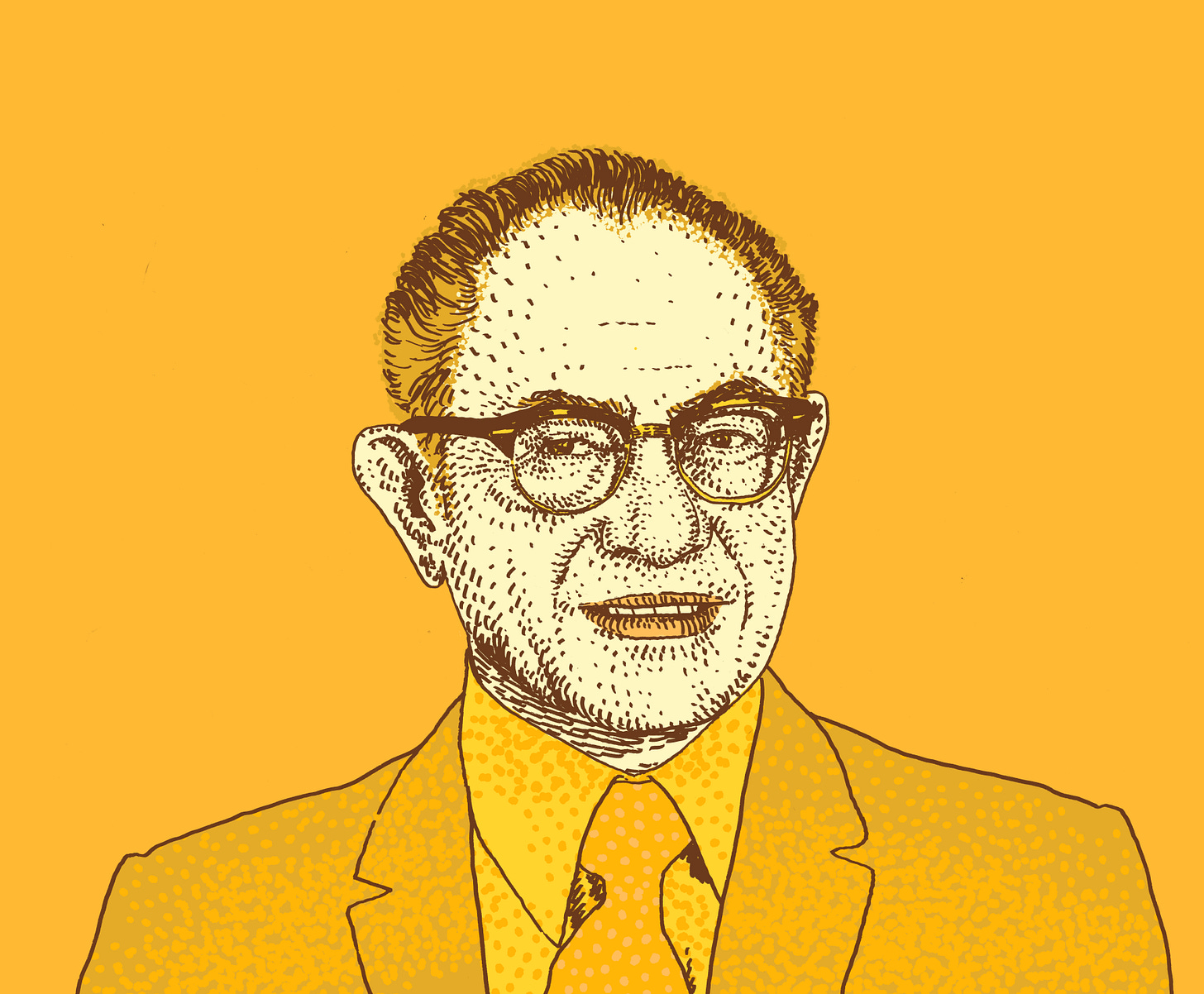

The Zamboni was invented in 1949 just outside Los Angeles in Paramount, California by a man named Frank Zamboni. Frank was the son of Italian immigrants. (They came to America separately, met in the 1880s, bought a farm in Idaho; you know, the usual story.) He was a mechanically minded young man. The family bounced around. He went to trade school. He learned to fix cars. Along with one of his brothers, he started a business manufacturing giant blocks of ice that could refrigerate train cars packed with produce from the bountiful fields of California as they steamed to parts of the country that were not as blessed as with fertile soil and warm weather.

The ice business couldn’t last forever. In the late 1930s, air conditioning and refrigeration technology advanced to the point that it just didn’t make sense to load train cars with big old ice cubes. So the Zamboni brothers sold the business. But they held onto the ice-making machines they had spent years buying, building,and maintaining. They used them to open up an ice rink across the street. They called it Iceland. (This was a confusing choice of names. They could have at least gone with Ice Land. Or Ice World. Or Ice City.)

Here’s a description from what is probably the closest thing to an “official” history of the Zamboni, a 2001 article from Fra Noi, a monthly magazine about Italian American culture. As you can infer, Iceland actually opened as an open-air facility, which considering the weather in southern California, is pretty insane:

In January 1940, with their cousin Peter Zamboni, the brothers opened Iceland as one of the largest ice rinks in the country with 20,000 square feet of skating surface. The 100 by 200-foot open-air arena could accommodate 800 skaters. In May 1940, a dome was added to protect the floor from the warm southern California sun. Approximately 150,000 skaters used the rink yearly.

To give some context, a standard NHL ice rink is 17,000 square feet. So we’re not talking about an ocean here. But it was a large space: a lot of ice to maintain -- and maintaining a sheet of ice is not as simple as keeping the temperature cold. Ice requires a lot of love and care: especially when it’s being trod upon by thousands of ungainly, awkward ice skaters holding hands on dates.

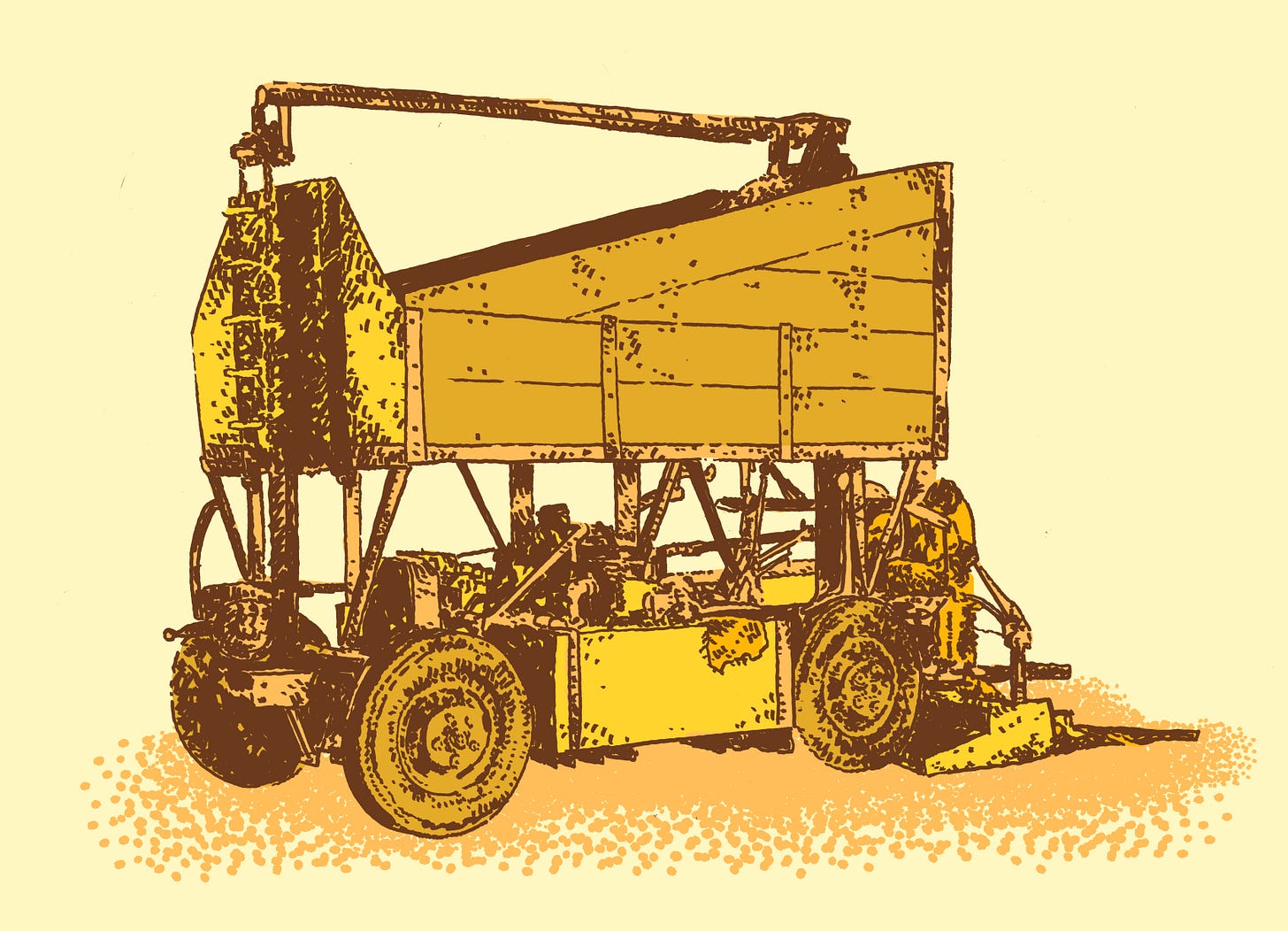

Frank Zamboni thought Iceland could do better than the slow, tedious process it had in place to manually resurface its rink. This process involved a tractor pulling a scraper, then men walking behind it spraying the surface down with fresh water, squeegeeing the dirty water, then finally spraying another clean layer. It took an hour-and-a-half, during which paying customers couldn’t use the rink. That was bad business.

So Frank bought a second tractor and he began to tinker. He wanted to create a one-step ice resurfacing process. The machine would have to be able to scrape, to spray, and to hold the dirt snow collected by the scraper. It took him years. Imagine a man: a father, a successful business man in his 40s, obsessing over this invention. Nobody had even considered a motorized ice resurfacer. He must have seemed at least a little bit crazy to the people who knew him.

The tractor experiment failed. But he kept tinkering and tinkering. Finally, in 1947, Frank had his breakthrough. In the back room of Iceland, he created a sort of Frankenstein’s monster of a machine built on the foundation of an old Jeep and a bunch of war surplus supplies. And it sort of worked -- but it kept sliding around on the ice.

He tried again. More war surplus parts. Pieces of the previous near success. And in 1949, Frank actually did it: the Zamboni as it came to be known, after its creator, had four wheel drive to prevent sliding all over the ice. It had an adjustable blade that the driver could simultaneously operate. It had a tank high up in the back to collect dirty ice shavings. And it qualified for a U.S. Patent.

And then, suddenly, the Zamboni existed. The problem of ice resurfacing was effectively solved. This is especially appealing to me right now: the notion of a singular problem and a singular genius and a singular solution. If only the world we have now could be fixed by a million Frank Zambonis.

At first, Frank did not think to sell the machine. He built it for his own personal use, and the Zamboni only existed in Iceland. Meanwhile, Frank kept improving on the design. And visitors to the rink became infatuated with the machine.

So Frank began to sell them. One time he drove a Zamboni literally up the highway to deliver to a rink in Berkeley. (He crashed along the way, but the machine and driver were both okay; Zambonis were built on Jeep chassis). Slowly, the Zamboni became its own business, spun off from Iceland. By the late ‘70s, the Zamboni that we now identify as a fixture in hockey rinks around the world had emerged. A decade ago, the Zamboni company, which is still based in Paramount across from Iceland, released its first electric Zamboni.

Frank died in 1988. He lived long enough to see his machine become ubiquitous, and his name become the kind of brand so powerful that it transcends the actual brand itself: like Kleenex. There are in fact other ice resurfacing machines. But as the official website for the Zamboni Company states: nothing else is even close.

Related Reading

I once tried to visit the Zamboni factory in Paramount as a reporter but was repeatedly turned away and redirected to the company’s online archives. It was a bummer, but I have to admit: the archives are very impressive.

Here’s the Fra Noi story on Frank Zamboni written by Joseph Scafetta Jr.

Here’s a stop motion Lego video featuring a Zamboni and North America’s favorite song about Zambonis:

STEALING HOME

Is still for sale! If you haven’t please consider picking up STEALING HOME from your local bookstore. And if you liked the book, please feel free to review it on Amazon or Goodreads, or share it (in addition to this newsletter) on your favorite social media website or app.

Sports Stories Jr.

If you have kids, or know kids who want to write+draw their own Sports Stories, it’s not too late to send them our way! We’d love to publish them. Just respond to this email with your (kid’s) submission.

April 27th is National Tell a Story Day. That week, we’ll send out an issue full of awesome kids Sports Stories.

Homework

I miss the Zamboni. What weird sports ritual do you miss? Please comment, or email us, or, if you prefer, reflect silently!

This has been Sports Stories by Eric Nusbaum (words) and Adam Villacin (art). If you have any questions, comments, or concerns, please reply to this email or contact enusbaum@gmail.com. We’d love to hear from you.

Sports Stories is 100 percent free. If you enjoyed this week’s newsletter, and want to show your appreciation, the best way to do that would be to sign up, share it on social media, or forward it to someone you think might enjoy it too