Blood in the Water

The 1956 Olympic water polo match between Hungary and the USSR was fraught with revolution and ended in violence.

Welcome to Sports Stories, a publication at the intersection of sports and history. Sports Stories is written by Eric Nusbaum, illustrated by Adam Villacin, and delivered to your inbox every Tuesday.

If you’re not already a subscriber, please sign up here — we have both free and paid options. Paid subscribers are entitled to our eternal gratitude as well as cool swag including postcards featuring original art by Adam.

There are some sports that make your body hurt just to think about: long distance cycling is one. Boxing is another. But perhaps the most brutal of them all is water polo: a grueling combination of treading water, swimming, throwing, catching, and no holds barred wrestling -- half of which occurs under the surface where the refs can’t see what’s happening.

In its primal form, water polo was essentially an offshoot of rugby played in the streams and rivers of Great Britain beginning in the mid 1800s. There were no actual goals -- you scored by placing the ball on the opposite shore, or side of the pool. Goalkeepers stood outside the water, and literally leaped down on the heads of prospective scorers to stop them.

Gradually, the game became formalized. In the late 19th century, it began to spread around Europe and to the United States. But it never stopped being violent; it never stopped being demanding. This week’s Sports Stories is about a water polo match that is widely viewed as the most violent of all time; it also happens to be widely agreed upon as the most important.

The men’s water polo semi-final between Hungary and the Soviet Union at the 1956 summer Olympics in Melbourne was one of those moments where global events and the luck of the sporting draw seemed to perfectly rhyme. In the water, it was a match charged by fear, anger, and desperation; from the outside, it was seen through the lens of revolution. There’s a reason it has become known as the Blood in the Water Match.

We should begin with Hungary. If you look at Hungary on a contemporary map, you see a small to medium-sized country nestled in Central Europe, notably without any coastline. But Hungary has a vibrant aquatic history and culture. Hungary is blessed with more than a thousand thermal hot springs, which over the centuries led to the establishment of pools and spas all over the place.

In the early twentieth century, Hungary dominated water sports on the global stage: first in swimming and diving, then, beginning in the 1920s, in water polo. Among other things, Hungarian players are credited with inventing the dry pass—that’s where you pass the ball to a teammate above water. For a decade in the 1930s, they didn’t lose a single match.

During World War II, Hungary’s government entered into alliance with Nazi Germany. After the war, it was occupied by the Soviet Union. By the 1950s, the country had been brutalized first by its own fascism, and then by Stalinism as a Soviet satellite state. Suffice to say the 1940s and 50s were not an easy time for Hungarians. And After Stalin’s death in 1953, things got really messy.

We’re not going to get too deep into Hungarian politics here: it’s complicated and quite frankly, I don’t feel I have a good enough grasp on the nuances of this history to write about it with any kind of authority. But the important thing to understand for the sake of this is that by the fall of 1956, a series of events had taken place that led the people of Hungary out to the streets to protest Soviet oppression.

Meanwhile Hungary also remained an absolutely water polo-mad country. Club matches drew huge crowds. The national team had dominated the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki and was still strong. Before the 1956 games, the team’s coach brought in a new player -- a talented young outsider named Ervin Zador. Zador was practically still a kid. He had come from a minor club. But even with no international experience, he found himself a natural fit amongst the world’s best players.

For one thing, Zador could handle the outrageous training regimen the Hungarian team went through. In the winter, the Hungarian team would ski every day -- but instead of taking a lift, they would hike up to the top of each run. There was swimming training, ball handling, work out of water and in the water. But what really separated them was leg work: churning and churning under the surface because the stronger you were, the higher you could lift your torso up out of the water, the more powerful and accurate you could be with the ball.

“We were literally walking on top of the water as a team,” Zador said years later.

In the runup to the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, the Soviet Union sent its own water polo team to the Hungarian training facility outside of Budapest to watch the greatest players on earth and scrimmage with them. The Soviet team had been a disappointment, and the country’s sporting leadership thought they could learn something from the Hungarians.

“At that period in time, they were our idols,” one Soviet player recalled years later. “They were significantly better than us.”

A sense of kinship grew between the teams -- but also a rivalry. Six months before the 1956 games, the Hungarian team traveled to Russia for a match with the Soviets. The match was vicious, and the Hungarians felt that the local refs were working against them. Afterwards, the teams brawled in the locker room.

The 1956 Summer Olympics were to be held in Melbourne, Australia which means that the games were not played in the northern hemisphere’s summer months but in fact began in November. In the weeks ahead of the opening ceremony, the Hungarian water polo team was holed up in its training facility. This is where they were in late October as peaceful protests on the streets of Budapest were violently repressed; this is where they were as those protests turned into a full-on armed revolution -- a revolution that for a moment seemed to have been successful, as the Soviet-backed government collapsed and the USSR seemed to withdraw from Hungarian affairs.

Hungarian revolutionaries cut the hammer and sickle emblem out of the country’s red, white, and green striped flag. The fate of the Olympic delegation was in flux -- but the water polo team came to believe that if they did indeed get to travel to Melbourne, it would be to represent a free and independent Hungary. They had been isolated from the violence. They could hear the gunfire from the hills where they were training outside the capital, but they had no true sense of what was happening.

The isolation was terrifying in its own manner. The fate of the country hung in the balance, and the water polo players didn’t even know how their families were doing. It was too much for Ervin Zador. One day, he simply left the team. Just 21 years old, he walked 15 miles back to Budapest to seek out his parents.

“I was scared, scared, just totally scared. I was terrified but I just kept walking. Pretty soon I was home, I walk in there and my mother turns around and smacks me. Says ’“you stupid, what are you doing here? You risk your life.’”

Zador’s mother told him to stop worrying about her -- that he would need to take care of himself from now on. He spent a couple of hours with his parents in their apartment and then walked back to the training facility, another 15 miles. The next day, the team was whisked off on a bus to Czechoslovakia. From there, they would travel by airplane to Melbourne. The players had no idea that on November 4, Soviet forces would enter Budapest. The revolution was short-lived. The Hungarian people had anticipated help from western countries like the United States based on what they heard on Radio Free Europe broadcasts. But the help never came.

The water polo team was oblivious to all of it. They only learned that the USSR had returned to power in Hungary after they arrived in Melbourne on November 20. The one team member who knew English read the news when he happened to pick up an Australian newspaper.

Before the games began, the team removed a Communist Hungarian flag at the Olympic Village and replaced it with a flag of free Hungary. They were the most visible athletes from a country that was now at the center of world events. Western countries offered the players asylum should they not want to return. Zador told his teammates he would not return to Hungary. He was not the only one. The question of whether or not to return divided the Hungarian team before play even began.

But they pulled it together. Despite everything happening back home, and despite having spent a month out of the water, the Hungarians cruised through round robin play to set up a semifinal match against none other than the Soviet Union.

Sports mean as much as we decide they do. In this case, the world decided that a water polo match between the Soviet Union and Hungary meant a great deal. It meant everything. It had only been a month since tanks bearing the letters CCCP rolled into Hungary.

The game was brutal and intense but it was not necessarily close. The Hungarians had introduced a new strategy in Melbourne, playing a stifling zone defense and then scoring on furious counter-attacks. It worked effectively against the Soviets just as it had against the Americans, the British, the Italians, and the Germans.

In the match with the Soviets, elbows and fists flew freely. There was penalty after penalty. But Zador scored two times and Hungary built a 4-0 lead. Then, toward the end of the match, Zador switched to cover a Soviet player named Valentin Prokopov. He later recalled that as soon as he switched onto Prokopov he started running his mouth: calling Prokopov and his family and the entire Russian team names.

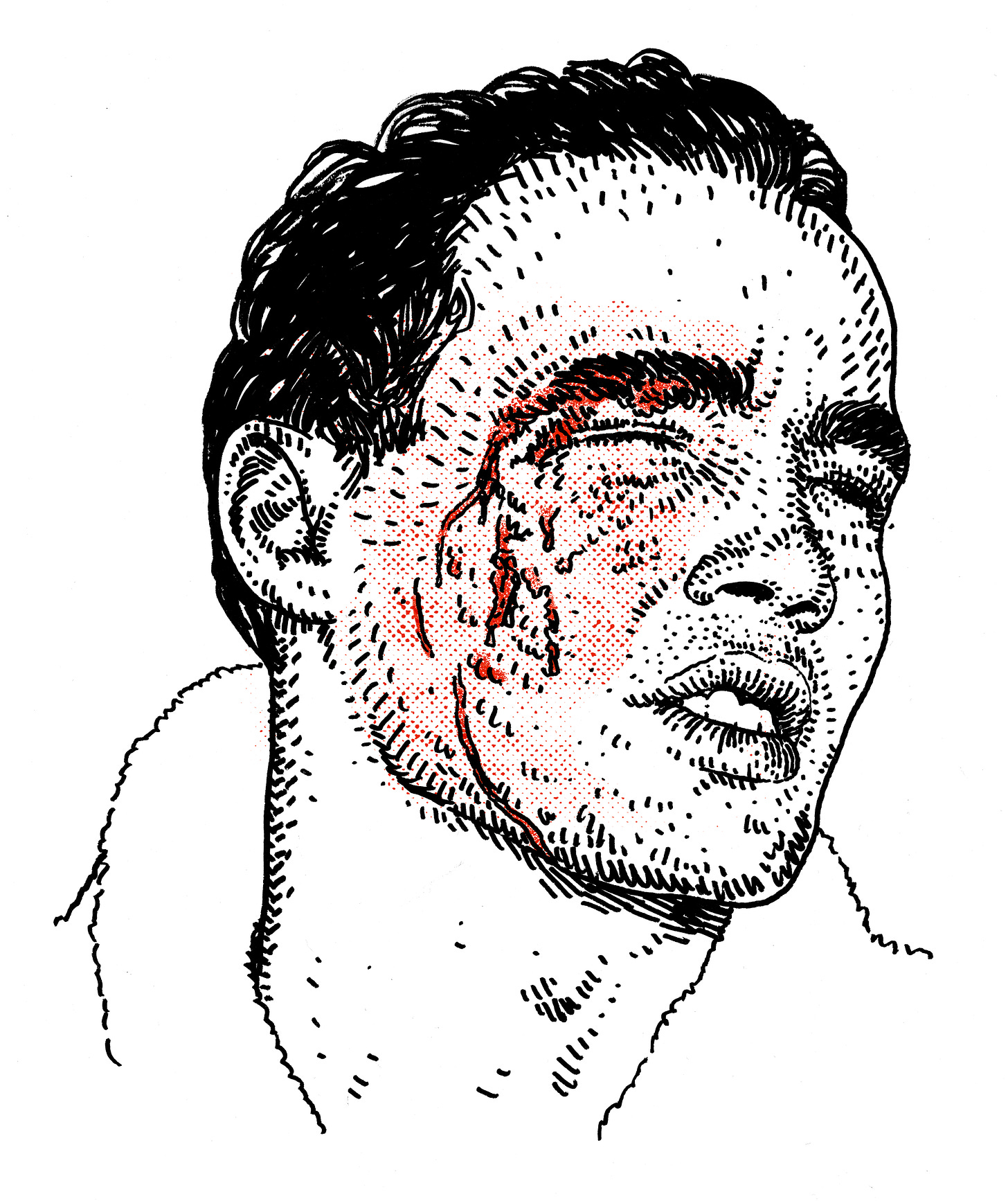

With about a minute left, Zador thought he heard a whistle. He turned his head to look for the referee. He was met instead with a vicious blow from Prokopov. The shot split open his eye and sent him down below the surface When he emerged, the pool was running red with blood. Blood dripped down from his eye, over his chest, and onto the floor below him.

“He looked like he just stepped out of a slaughterhouse,” one of his teammates said.

It seemed as if the entirety of the Soviet-Hungarian relationship had come down to this moment. The players stopped playing, the ball floating unattended in the bloody water. The crowd grew deafening. Angry fans leaped barriers and nearly started a riot. With a minute left to play, the referee called the match off. Hungary had vanquished the USSR 4-0. The players were ushered into their respective locker rooms. They never shook hands afterward.

The match itself became an international sensation. The Hungarians went on to defeat Yugoslavia 2-1 for the gold, without their teen sensation Zador, who was too badly injured to play. But all anybody could talk about was the blood in the water.

Was it fair to label the Soviets a dirty team? After all, water polo is a dirty sport.

“It’s part of water polo, said Nick Martin, a member of the Hungarian team. “As the Russians say, water polo nyet ping pong”

“They were barbarians in other ways, but not in this game,” said Zador.

The Soviets were just playing to win -- and besides, they were living in an alternate reality. They believed what the press in Russia told them; what their government told them. They believed that the USSR had liberated Hungary on November 4, 1956. It was that simple.

Was Prokopov a bad guy? Or was he just doing his job? He was an athlete, not a politician or even a soldier. Decades after the match, his legacy remains intact as the man who hit Ervin Zador. When you think about it, it’s absurd that this blow struck in a swimming pool during an amateur sporting event has become part of the story of a brutal counterrevolution. But then again, it is part of the story.

Zador himself stayed true to his word. He could have returned to Hungary a hero: he was young and famous and had a great future ahead of him in water polo. You can be the player of the century, one of his teammates told him. But after the Olympics, he sought asylum in the United States.

“You can’t be the player of the century with a muzzle in your mouth,” Zador said years later.

Related Reading

Ervin Zador settled in northern California. He had a family and coached water polo. Among the players Zador coached was a talented swimmer whose father’s family had emigrated from Hungary generations before. He was a high school All-American in water polo, but he would really make his name in swimming. His name was Mark Spitz.

Spitz would go on to become one of the greatest Olympians of all-time. He also provided the narration for a 2006 documentary about the Blood in the Water match called Freedom’s Fury. The doc, which somewhat oddly, was produced by Quentin Tarantino and Lucy Liu, is an awesome look back at the game and the circumstances leading up to it. The quotes I included in this story are from there. You can stream Freedom’s Fury on Amazon for just $2.99.

The filmmakers interviewed Hungarian and Soviet players, journalists, professors, freedom fighters, and even Nikita Khrushchev’s son Sergei. But the best part is the final scene: 50 years after the game, the players are reunited at one of Budapest’s lavish spas. It’s incredibly powerful to watch these old guys back in the pool throwing the water polo ball around.

For a good writeup on Zador and the match, I recommend this piece by Miles Corwin from Smithsonian Magazine. The match was also reported on widely at the time.

Sports Stories is an independent publication, and our best chance at growing is by word of mouth. If you have dug this or any issue of Sports Stories, please do us the solid of sharing it with a person you think might dig it too.

Thanks for reading Sports Stories. We’ll see you next week.

Great article.

In the 1975 Pan Am games in Mexico City we had blood in the water and the locker room after our win over Cuba.

I was blindsided with several closed fist punches by Jorge Rizo who I was guarding and he split my skin near the eye. He was given a brutality foul and missed the next game. Eric Lindroth and Harpo were attacked in the locker room as they were taking showers.

Cuba and the USA always had tough games but this was one was extreme.