The Epic, Forgotten 1971 Women's World Cup

In 1971, an "unofficial" Women's World Cup in Mexico drew massive crowds. It should have been the beginning of a new era for women's soccer -- then FIFA went offsides.

This week’s Sports Stories is being sent to you directly from Mexico City. When I lived here many years ago, I wrote a fair bit about sports, especially lucha libre (a subject we visited in an early issue of Sports Stories) -- but for the most part, I tried my best to avoid writing about the sport that dominates life in this city and country: soccer.

The truth is, I always feel like a poser when I write about soccer. I like it. I appreciate it. But I can tell there’s so much more going on under the surface. I know that other people understand it, and feel it, on a much deeper intellectual and emotional level. I’m so insecure about this that before I wrote my one soccer dispatch-- about the Mexican men’s national team before the 2014 World Cup -- I literally read a 450-page book on the history of tactics. (Inverting the Pyramid) by Jonathan Wilson; I didn’t plan on actually finishing it, but it was really good!)

So with all that said: this Sports Stories is about soccer. In particular, it’s about the most interesting soccer tournament this city has ever hosted: not the 1970 World Cup that was Pelé’s last great moment of international glory, and not the 1986 World Cup that saw Diego Maradona’s Hand of God goal.

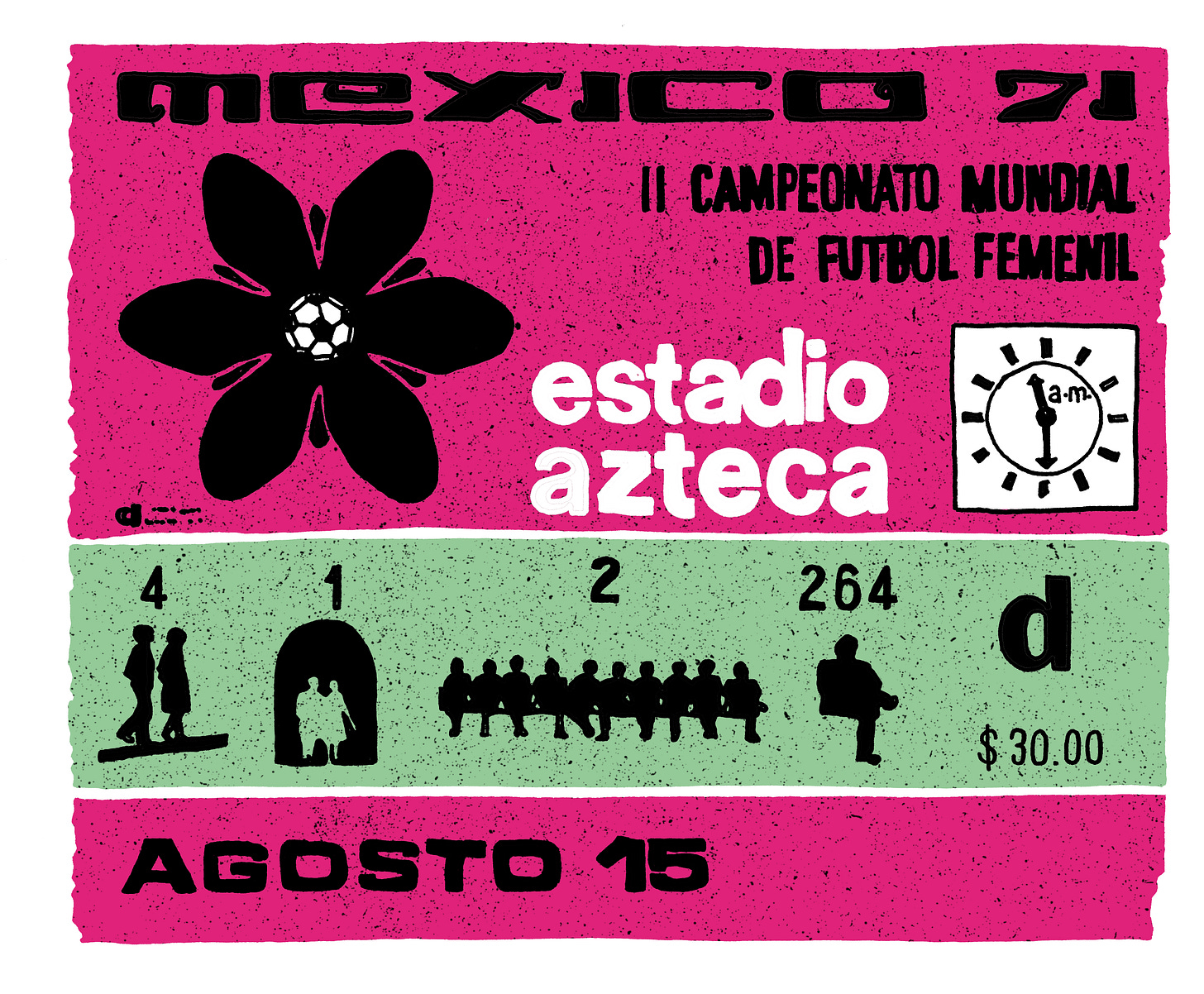

This is about the time that 110,000 people filled the country’s biggest and most important stadium -- Estadio Azteca, where Pelé and Maradona made their legends -- to watch Mexico face Denmark in the final match of an unsanctioned, unofficial and massively successful women’s world cup tournament that was sponsored and almost completely paid for by an Italian beverage company.

The World Cup in 1971 was an inflection point for women’s soccer. Or at least it should have been. Up until the tournament, FIFA, the sport’s governing body, had a policy of aggressively ignoring women. This despite the fact that women had been playing organized soccer for as long as men -- including in well-attended, high-level matches in Europe.

In the 1960s, FIFA’s position regarding women’s soccer was looking increasingly ridiculous (and more obviously sexist) by the day. Women were claiming more space for themselves in previously male-dominated parts of society. There was obviously a market for women playing organized soccer. And yet nothing changed. Sensing this market in Europe, some women’s soccer boosters began to organize international soccer tournaments to fill the gap that FIFA didn’t want to. They created a group with the acronym FIEFF, which was later shortened to FIFF. They held their first tournament in 1969.

Here’s the writer Roger Domeneghetti in The Blizzard:

Its commercial attraction was becoming apparent to a range of businesses who were in a position to exploit it thanks to their marketing structures and media contacts. Fieff was backed by several of the businesses behind Italian women’s league clubs, key among them the Italian drinks company Martini & Rossi.

In 1970, the company sponsored a tournament called, no joke, the Martini & Rossi Cup in Italy -- this became essentially the first unofficial women’s world cup tournament. It was a big success. And Mexico even came all the way across the ocean to compete with the European sides.

At the time, organized women’s soccer was just beginning to take off in Mexico as well. Professional clubs began organizing women’s teams to compete in an amateur league that played across the country. It was from these clubs that the Mexican team was chosen. They traveled to Italy with basically nothing: no money, no formal training as a team, and no support system back home. Their uniforms were paid for by Martini & Rossi, but they didn’t have uniforms to wear for the opening ceremony; they didn’t even have a Mexican flag. For the procession, they borrowed an Italian flag and attached an Aztec calendar to the center in place of the national shield.

And yet the tournament made an impression on the players, and on Mexican officials. One Mexican player, Alicia Vargas, led the tournament in scoring, and gained the nickname “La Pelé.” It was decided that the following year, Mexico would host a bigger, more “real” Women’s World Cup event using the same facilities that the men had used in the men’s 1970 World Cup.

The success of the previous year’s tournament in Italy had piqued the attention of FIFA, who banned the Mexican Futbol Federation from being involved in any kind of unsanctioned women’s tournament. (Not that they were interested in providing any other alternatives.) That led the World Cup organizers to use only private facilities. Thankfully, these included Azteca -- the country’s largest most iconic stadium.

Six teams came to Mexico in 1971: England, Italy, Denmark, France, Argentina, and Mexico. The event was promoted ceaselessly in Mexico: it was all over TV and all over the papers. Members of the English team described the surreal experience of going from being nobodies back home, to landing in Mexico City as celebrities, and being shuttled straight to a television studio for interviews.

The tournament’s organizers spared no expense in promoting the event -- this in itself was a novelty: treating a women’s tournament as if it was a serious thing that people would actually want to watch. The matches were televised in Mexico, and stadiums were filled. It wasn’t a perfect example of feminism: the tournament’s mascot was a weirdly flirtatious little girl in pigtails named Xochitl; promoters ensured that the goalposts were painted pink; “It’s a natural combination of the two passions of most men around the world: soccer and women,” one of the tournament’s organizers told the New York Times.

Over the final days of August and the early days of September, the tournament went off relatively smoothly. Mexico games especially drew huge crowds. The team became somewhat of a local phenomenon as they advanced through group play, and into the finals against Denmark.

Then they did something unexpected. The team had been playing for free for a year, since the 1970 tournament. They had been uncompensated for their practice time, and for their time competing in actual games -- even as organizers and sponsors raked in money from the massive gates. So before the final, the Mexican team asked for some compensation.

This did not go over well. The general response in the Mexican press was along the line of “who do these girls think they are?” As the hours ticked away before the final, it became increasingly clear that no payment would be coming. The team could have sat out, but while doing so would have been a way to stick it to the tournament organizers — it would have also been a disappointment to literally an entire nation. So it was decided: they would play. The final was held on September 5, 1971. 110,000 fans poured into Azteca for the game. I’m no soccer expert, but I’ve been to Azteca enough times to understand that it’s a special experience. Simply approaching the stadium after a (presumably) long journey across the vast city feels like an act of pilgrimage. Then, when you’re inside, you feel tiny: so far away from the action on the field and yet absolutely a part of it. Estadio Azteca is not beautiful, but it is mighty. And the women on the field felt the full force of its might. The crowd matched the largest men’s World Cup draws. Players remembered looking up and seeing people sitting in the aisles. On the field, the Mexican team could not put it together. It was an uninspiring performance, and Denmark won 3-0.

However, the feeling was that this was the beginning of something great; that after Mexico City, women’s international soccer would blossom.But it didn’t, at least not for decades.According to Domeneghetti, after the tournament, UEFA (the European Football Association) felt so threatened by the possibility of commercially successful women’s soccer that it requested its member associations “take control of the women’s sport” so as to avoid future competition. Some countries took this seriously and developed training programs for women, but most didn’t.

Meanwhile, FIFA lifted its ban on women’s soccer. But because this action was accompanied by zero funding for the women’s game, nothing happened; women’s soccer was now under the control of the men who had wanted nothing to do with it previously, and wanted nothing to do with it still.

It would be twenty years until the first “official” Women’s World Cup was held, in 1991.

Related Reading

I would start with the aforementioned Roger Domeneghetti essay in The Blizzard. It’s a nice piece of historical writing that focuses especially on the England team. (They are a fascinating story in their own right.) There’s also a cool little Google Arts & Culture page (not sure what these are exactly) showing some primary sources about the early history of the Women’s World Cup, and including more on England in particular. For yet another look at the English side, here’s a BBC story on the ‘71 team.

The best resource on the Mexican team I could find was this awesome short Spanish-language documentary featuring the voices of the players. It also goes into the near-strike before the final game.

For a little more (also in Spanish on the tournament from a Mexico perspective check out these stories in El Universal and La Vanguardia.

This has been Vol. 15 of Sports Stories by Eric Nusbaum (words) and Adam Villacin (art). If you have any questions, comments, or concerns, please reply to this email or contact enusbaum@gmail.com. We’d love to hear from you.

Sports Stories is 100 percent free. If you enjoyed this week’s newsletter, and want to show your appreciation, the best way to do that would be to sign up, share it on social media, or forward it to someone you think might enjoy it too.