The Redemption of Norm Bass

Norm Bass was a multi-sport superstar until his body betrayed him. This is the story of how he made it back.

Today is September 24th, which means that it’s been exactly one year since we published the first issue of Sports Stories. It feels like we just started. It also feels like it’s been a decade. Thank you for sticking with us. Thank you for finding us. Thank you for being part of our community.

The very first issue of this newsletter was about a Chinese table tennis player named Rong Guotuan. Rong’s is a heartbreaking story. And in that sense, maybe it is more apt for right now than it was even when we first shared it. But hearts can only take so much breaking.

We’re going to get to table tennis this week too. The subject of this week’s newsletter, Norm Bass, would tell you that hearts can only take so much breaking and that bodies can only take so much beating. He might tell you that humans are capable of miraculous things. He might tell you that life’s not fair, but that doesn’t make it any less beautiful.

Look out your window. It’s a mess out there right now. It’s a mess for everyone, and I’ve been thinking about the fact that for us to pull through it requires not just collective action or structural change but so many individual acts of perseverance. We’re in this together and we’re also always, to a certain extent, alone. (I’m resisting temptation here to go into an extended riff on how baseball is like life: you’re on a team, but you’re also out there in the field by yourself.)

Anyway, no athlete I can think of has had a career like Norm Bass. No American I can think of has had a life like Norm Bass. He was a a Forrest Gump type figure: crossing paths with everyone from Aretha Franklin to Cassius Clay to Bill Clinton. He was an early multi-sport superstar who overcame health problems that should have wrecked his athletic career for good.

Norm Bass is 81 years old now. He was born in the tiny town of Laurel, Mississippi. When he was a toddler, his family moved to California -- to a small Bay Area city called Vallejo. Like so many other people, Norm’s father found work in the war industry. The move to California was a ticket to opportunity and it was an escape from the Jim Crow south.

But Norm’s father did not let the lessons of Mississippi go unlearned. His boys were athletes -- Norm and his older brother Dick. You have to be twice as good, the boys were told. You have to be twice as good as the other guy if you’re going to play. You have to be twice as good as the white guy. Norm’s father had been a boxer and a semi-pro ballplayer. He knew what he was talking about. So the boys worked twice as hard. They ran miles and miles every morning. They played harder. They talked more trash.

Then one morning Norm couldn’t open his eyes. He was just 10 years old. At first the family thought he was kidding around, because Norm was a practical joker. But this was real. It was like his eyelids just didn’t work anymore. His father took him to the hospital. By the time they got him admitted, Norm couldn’t hear anything either. A few days later, he couldn’t move his legs. Then the sickness came for his voice. They moved him to another hospital. It was meningitis.

Norm was 10 years old. He was highly contagious and he was totally isolated from his family. He remembers the priest coming in to read him his last rites. He remembers being alone. Nobody knew how he got sick. But somehow he started to get better. LIttle by little. He could walk again, speak again. This was important because Norm loved to run his mouth. The hearing came back slower. Norm went to a special school to learn to read lips.

But meningitis could not slow Norm Bass down for long. Nothing could, really. He grew into a magnificent athlete. He played four sports in high school—baseball, basketball, football, and track—and excelled at all of them. His brother Dick was a superstar as well and earned a football scholarship to the University of the Pacific in Stockton. Norm would follow him there, but he would not follow in Dick’s footsteps forever.

Dick Bass became an early draft pick of the Los Angeles Rams and a superstar running back in the NFL. He was shorter and more powerfully built. Norm on the other hand was tall and lean and fast. What he wanted above all was to play basketball. But the football scouts liked him too, and the baseball scouts liked him more than anybody.

Why did Norm choose baseball? Because he had to.

It’s worth stating here that Norm tells his own story better than anybody else could. A lot of the material in this issue comes directly from Norm’s own recounting of events. Before the pandemic, Norm sat down for a long interview with Denny Lennon’s awesome Sports Stories podcast (no relation, officially speaking).

The way Norm put it was like this: he got a girl pregnant and found himself in a marriage he did not especially want to be a part of. The $4,000 signing bonus he was offered by the Kansas City A’s would help take care of his child -- and have the added benefit of getting him out of California. This was still the 1950s, and the A’s couldn’t send a Black player to their affiliates in the south. (Baseball did not magically integrate with the arrival of Jackie Robinson, despite how that story is told today.) So Norm’s first minor league stop was in Pocatello, Idaho.

These days, Norm claims that he was throwing 100 miles per hour way back when. There weren’t radar guns at the time, so there’s no way to verify this claim, but it’s fair to believe that he really did throw heat. It’s also fair to say that the results never quite lived up to what that heat might have portended. Norm made his debut with the A’s in 1961. He was boisterous and funny and loved the spotlight, which meant he was a great fit for the team and its charismatic, colorful owner Charlie O. Finley.

But by the time Norm reached the majors he already knew something was wrong. It wasn’t like what happened to him as a boy, but his body was betraying him. It was slower. And it started in his hands. One offseason, Norm played a pickup basketball game with his brother Dick and a few players from the Rams. One of the players was their team doctor, a young guy named Robert Kerlan. Kerlan noticed Norm’s hands and told him, off-handedly, that he thought he had arthritis. Norm nodded. He put it out of his mind.

Every start for the A’s was a battle against a body that slowly seemed to be decaying. His arm was hurting. He couldn’t grip the ball the way he wanted to. But he was only 21 years old. It didn’t make sense. Norm’s first start was indicative of the kind of career he would have: he tossed a complete game victory, allowing just two runs. He also walked nine batters.

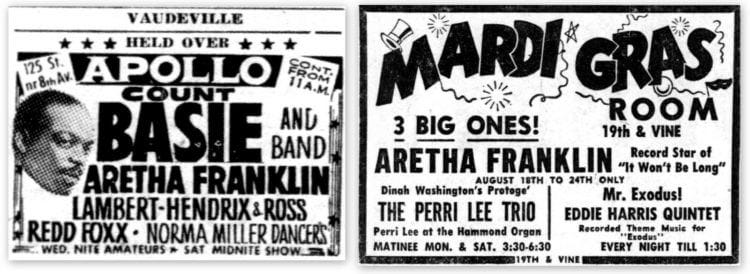

That 1961 season in Kansas City would be the best of Norm’s career. They were a lousy team, and Norm was fairly mediocre if we’re being honest -- but he was making the most of the experience. In June, he gave up a towering home run to Roger Maris who was on his way to breaking Babe Ruth’s single season record. In August, he claims he had a brief fling with a young soul singer who was in Kansas City after releasing her first album earlier that year. Her name was Aretha Franklin.

Norm tells a convoluted story of being introduced to Aretha by a mutual friend at a club called the Mardi Gras in August of 1961. He says that after they met he left her tickets to a game against the Orioles -- that he pitched a gem and that his A’s won in extra innings. When I heard this story, I admit I was skeptical. Aretha Franklin??? But I did some digging. Aretha Franklin was indeed performing in Kansas City that August at a club called the Mardi Gras. Norm Bass did indeed pitch a gem on August 22 of that year against the Orioles. And his A’s did indeed win that day in extra innings.

This was just how Norm’s life was. He was around famous people all the time. He played cards with Cassius Clay back in LA. He played an exhibition against the Harlem Globetrotters. But none of the fun and none of the glamour could prevent his body from breaking down. He made it through two more seasons with the A’s before his major league career ended. They sent him off to the Mayo Clinic. They sent him everywhere -- nobody could figure out what was wrong with his arm, with his hands.

In 1964, Norm got an invite from the Denver Broncos to come to their training camp in Boulder. He hadn’t played football since high school -- but why not? What did he have to lose? It was a miserable experience. But he threw himself into it. All of himself. He made the team as a kicker and safety. He was swallowing 16 aspirins a day. He was getting acupuncture off the books. He was desperately changing his diet. He made it through one game.

By 1965, it seemed that sports were over for Norm. He was finally diagnosed officially with rheumatoid arthritis. That means his body’s immune system was attacking his own joints. It was horrible. Doctors didn’t know if it was connected to the childhood bout with meningitis, but at least now Norm understood what was happening to him. He got a job running computers at McDonnell Douglas aircraft. He disappeared from the public eye. He was only 26 years old.

For 15 years, Norm went to work at McDonnell Douglas. He came home. These were not necessarily happy years. Norm had done everything right. He had worked twice as hard. He had demonstrated world class ability. And his own body had let him down. This was not the life he was supposed to have. The anger manifested in his relationship with his children. He was mean, he was violent, he was never satisfied with anything. Norm never drank or did drugs, but he sank into a kind of long, spiritual rut.

Then one day, he found himself watching a ping-pong match at a park in LA. Norm had played a lot of ping-pong as a kid. He loved it. He loved anything competitive. That day he saw a 40-year-old man beating up on a 12-year-old kid. Something about the scene got his blood going. Afterwards, he challenged the man to a match. He pulverized him. The man invited Norm to his ping-pong club. And that was the start of it. Norm found himself immersed in a new world.

In ping-pong, Norm found a sport his body allowed him to play. He used a light racket that he could manipulate with his weakened hands. His body did not allow him to take big aggressive swings, but he found he could push and chop at the ball; he could outsmart players. Once he had been a pitcher throwing 100 miles per hour. Now he was a junkballer table tennis player. And he loved it.

Norm’s life was changing. His marriage was ending and his new life as a table tennis player was beginning. He began to climb, slowly, out of the hole he had been in for decades. He began to let go of his bitterness. He found God. He found a new sense of purpose.

Norm also found a community in the world of ping-pong. He brought the same energy to the sport that he had brought to baseball and basketball and football. He was also an excellent player. He was still an imposing figure in the gym but he was decades older than the people he was competing against; he was beating them not with the grace and power of his youth but with smarts, with spin, with craft.

In 2000, Norm qualified for the American team at the Paralympic Games in Sydney. 40 years after he sat alone in a hospital room hearing his own last rites and 25 years after his professional sports career ended, Norm Bass found himself standing with a bronze medal around his neck as the Star Spangled Banner played. He found himself shaking hands with Bill Clinton at the White House.

He had disappeared once. Now he had made it all the way back.

Related Reading

I highly recommend the aforementioned interview between Norm and Denny Lennon. It’s available in podcast form here.

Norm was also the subject of a biography, written by his son Norman Delaney Bass III. The book is called Color Him Father: An American Journey of Hope and Redemption. It would be very easy for a book like this one to fall into cliche and into hagiography, but to Norman III’s credit, Color Him Father absolutely does not. It’s a powerful and open and at times unsparing look at the Bass family. Norman III doesn’t shy away from anything. It’s a truly admirable book.

Stealing Home

In addition to today (September 24) being the one-year anniversary of Sports Stories, it’s also the six month anniversary of the publication of Stealing Home. The book is still for sale, and if you just can’t get enough of LA and baseball and red scare politics, tonight I’ll be in conversation with the great Gustavo Arellano through the Glendale Library.